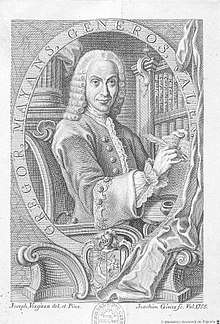

Gregorio Mayans

Gregorio Mayans y Siscar (1699–1781) was a Spanish historian, linguist and writer of the Enlightenment in Spain.[1]

Gregorio Mayans | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 9 May 1699 |

| Died | 1781 Valencia, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | Historian, linguist, writer |

Early life

Gregorio Mayans was born on 9 May 1699 in Oliva, Valencia, Spain. His father, Pasqual Maians, fought on the Austrian side in the War of the Spanish Succession and accompanied archduke Charles VI to Barcelona in 1706; this resulted in the later marginalization of Gregorio Mayans, who lived in Spain when it was dominated by the House of Bourbon. Until 1713, when he returned to Oliva, Mayans studied with the Jesuits of Cordelles, but his grandfather, a mayor named Juan Siscar, encouraged him in the study of law. He attended the University of Valencia, where he learned from the most distinguished of the novatores, men such as Tomás Vicente Tosca, Juan Bautista Corachán, and Baltasar Íñigo, who introduced him to the ideas of John Locke and René Descartes, which would become important in Mayans' later development.

In 1719, Mayans traveled to Salamanca in order to continue studying law. One of his professors, Borrull, put him in contact with Manuel Martí, dean of Alicante, who became his mentor and guided him in the study of the classics, Spanish as well as Latin and Greek. Martí introduced Mayans to the study of the Renaissance and the Spanish humanist of the sixteenth century: Antonio de Nebrija, Benito Arias Montano, Friar Luis de Granada, Friar Luis de León, Francisco Sánchez de las Brozas el Brocense, Juan Luis Vives, San Juan de la Cruz, Teresa of Ávila, and Miguel de Cervantes. Mayans dedicated the rest of his life to the preservation of this tradition, which he thought was being forgotten in Baroque Spain.

Early career and opposition

Mayans earned the Chair of the Justinian Code at the University of Valencia, but faced hostility from his colleagues in the Faculty of Law. In 1725 he published a work entitled Oración en alabanza de las obras de D. Diego Saavedra Fajardo (Prayer in praise of the works of Diego Saavedra Fajardo), and in 1727 he followed it with Oración en la que exhorta a seguir la verdadera idea de la elocuencia española (Prayer of exhortation to follow the true idea of Spanish eloquence), in which he criticized the excesses of the Baroque period and considered the Spanish and Attic simplicity of the Friars Luis, Vives, and el Brocense. In the same year the traveled to Madrid, where he met the director of the Real Academia Española (Mercurio López Pacheco, 9th Duke of Escalona) and the director of the Biblioteca Nacional de España (Juan de Farreras). He corresponded with Benito Jerónimo Feijóo y Montenegro for a time but broke with both him and Father Enrique Flórez due to the seeming superficiality of his thoughts.

At that time he defended a proposed reform of legal studies in order to de-emphasize Roman law and pay more attention to Spanish customary law, and also presented a general scheme of education reform to minister José Patiño, though without success. His recommendations included, for example, the teaching of Vulgar Latin instead of Ecclesiastical Latin, an idea that had already been proposed by the sixteenth-century Spanish humanist Pedro Simón Abril.

Later career and retirement

In 1740, after losing the favor of Arbuixerch, a religious official of the University of Valencia, and beset by various controversies, Mayans left and went to Madrid where he became the royal librarian. There, in 1732, he published his Epistolarum libri sex, which brought him into contact with humanists throughout Europe, and in 1733 his Orador Cristiano. He was an official of the National Library for seven years, and in 1737 he sent the Carta-Dedicatoria to Patiño, containing his ambitious plan of Spanish cultural and educational reform, but never received a response. In 1740 he retired to his hometown of Oliva, in order to dedicate himself to his studies, and began an active intellectual correspondence with other learned Spaniards and foreigners in both Latin and Spanish.

After retirement he married his cousin, Margarita Pascual, and in 1742 he founded the Valencian Academy, "dedicated to the recovery and exposition of ancient and modern memories concerning the things of Spain." His opposition to the España Primitiva de F. Javier de la Huerta y Vega, describing it as an "indecent fable opposed to the true glories of Spain", caused enmity between him and the Academies of Language and of History. When he edited the Censura de historias fabulosas of Nicolás Antonio he brought the Valencian Academy to the attention of the Spanish Inquisition. After the coronation of Ferdinand VI of Spain, however, the Marquis of Ensenada rescued him from his forced retirement and later Charles III of Spain restored his reputation and named him Alcade de Casa y Corte, an important administrative-judicial position. In 1776, he became a member of the Real Sociedad Económica de Amigos del País de Valencia. During this period he continued his discourse with local luminaries such as the Valencian physician and philosopher Andrés Piquer, Francisco Pérez Bayer, Muñoz, Cerdá Rico, Cavanilles, and Blasco. He dedicated his last year to preparing an edition of the Obra Completa (Complete Work) of Juan Luis Vives, but died unexpectedly in 1781.

Other works

Apart from the works already cited, Mayans edited the Advertencias a la historia del padre Mariana of the Marquis of Mondéjar and the works of Antonio Agustín. He especially admired Ambrosio de Morales and Juan Páez de Castro, and collaborated on the Diario de los Literatos under the pseudonym "Plácido Veranio". He wrote the monumental Orígenes de la lengua española (Origins of the Spanish language) (1737), which brought Juan de Valdés' Diálogo de la lengua into the light for the first time, and twice reprinted the Reglas de Ortographía (Rules of Orthography) of Antonio de Nebrija. In 1757 he composed a Rhetórica which is both an interesting anthology of Spanish literature and the best analysis of Castilian prose until Capmany's Teatro de la elocuencia española. Mayans also wrote the first biography of Miguel de Cervantes, published in 1738.

References

- Fernando Durán López (2005). Vidas de sabios: el nacimiento de la autobiografía moderna en España (1733–1848) (in Spanish). pp. 119–129. ISBN 978-84-00-08311-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gregori Maians. |