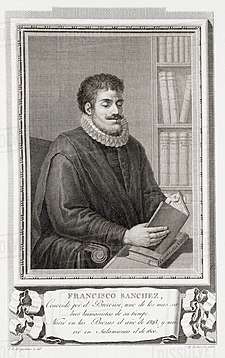

Francisco Sánchez de las Brozas

Francisco Sánchez de las Brozas (1523–1600), also known as El Brocense, and in Latin as Franciscus Sanctius Brocensis, was a Spanish philologist and humanist.

Biography

He was born in Brozas, province of Cáceres. His parents, Francisco Núñez and Leonor Díez, were noble but had little money. He was able to study thanks to the support of some relatives, and started in Évora, where he learnt Latin and humanities, and then in Lisbon. There he served Queen Catherine I and King John III of Portugal and remained in the court of the Portuguese kingdom until the death of the princess in 1545. Following the desires of his supporting relatives, he went to the University of Salamanca, where he studied Arts and Theology, which he didn't finish. There he met, among his fellow students, Juan de Mal Lara. Still a student, he married his first wife, Ana Ruiz del Peso, who gave him six children. A widower at the age of 32, in 1554, he married a relative of his first wife, with whom he had another six children. Since then he suffered economic hardship to support his family and must teach without pause. He receives the chair of Rhetoric at Salamanca in 1573, after a failed attempt in 1554, and in 1576 the section of Greek language, with a higher salary. He never obtained the chair of Grammar, despite two attempts. In 1584 he had his first difficulties with the Inquisition, although he was exonerated. As a consequence of his great critical mind (for him the greatest authority was reason) and his noncomformity towards authority, the censors restricted the diffusion of his works. A decade after his retirement, in 1595, a new inquisitorial process started, which was only interrupted by his death: he died on 5 December 1600, isolated in his home as a result of the house arrest imposed by the Inquisition.

The importance of the ideas of el Brocense in the reform of classical studies in Spain is, in the mid-16th century, comparable to that of Antonio de Nebrija at the beginning of the century. This appears in his Arte para saber latín (1595), in the Grammaticæ Græcæ compendium (1581) and, above all, in the Veræ brevesque Latinæ institutiones (1587), where he corrects Nebrija's method. Nevertheless, he is mostly remembered for his Minerva sive de causis linguæ Latinæ (Salamanca: Renaut, 1587), a Latin grammar in four books or sections (study of the parts of speech, the noun, the verb, and the figures) which, subjecting the study of language to reason, is one of the very first epistemological grammars and made him a European celebrity for several generations.[1] While the first grammarians of Humanism (Lorenzo Valla or Antonio de Nebrija) were still writing normative grammars based on the usus scribendi of the ancient authors, el Brocense took ratio (reason) as the cornerstone of his whole grammatical system. He acknowledged no other authority than reason and took to its ultimate consequences the logic of grammatical study.

He was determined to make everything fit within rational schemes, and granted in his grammatical interpretation a very important role to ellipsis, an essential tool of his system. In that search for rational explanations, he stepped beyond the limits of the Latin language to go as far as to foreshadow the universal grammar which is implicit in all languages. He is thus a most important milestone towards Port-Royal Grammar and Noam Chomsky's generative grammar. His Minerva was very successful, and had had 15 editions by 1761. The dense scholia by Scioppius appeared in the mid 17th century and would accompany the Minerva until the 19th century. The notes by Perizonius were written at the request of a publisher from Franeker in the Netherlands. They were included in the 1687 edition and were so successful that the same publisher reprinted it fraudulently in 1693.

He published editions of the Bucolics by Virgil (1591), some works of Ovid, the Satyres by Persius and the Ars poetica by Horace; commented editions of the Sylvae by Angelo Poliziano and the Emblemata by Andrea Alciato; and translations of Horace and of the Canzoniere by Francesco Petrarca. He wrote and printed Comentarios to the works by Juan de Mena and Garcilaso de la Vega (1582 and 1574 respectively). When he was accused of having identified the influences of Græco-Latin classics in the lyrical work of the latter, thus diminishing his poetic originality, el Brocense said that he didn't consider a good poet whoever didn't imitate the classics. He also wrote a great number of Latin poems and scholia.

He had a mainly formal understanding of literary beauty, as is revealed in his rhetorical treatises De arte dicendi (1556) and Organum dialecticum et rethoricum cunctis discipulis utilissimum et necessarium (Lyon, 1579). It is pertinent to point out here that he was processed by the Inquisition because he dared to criticise the literary form of the gospels. He favoured Erasmus of Rotterdam, and in his scientific works he shows the encyclopedic inclinations that were characteristic of Humanism, as in Declaración y uso del reloj español (1549), Pomponii Melæ De situ orbis (1574) or Sphera mundi ex variis auctoribus concinnata (1579). Among his philosophical works the main ones are Doctrina de Epicteto (1600), Paradoxa (1581) and De nonnulis Porphyrii aliorumque in dialectica erroribus (1588).

He had three encounters with the Inquisition: one, mentioned above, in 1584, where he was exonerated. The second one was in 1595, when he had already retired. The third, in 1600, was interrupted before its resolution due to his death, in Salamanca, at the age of 78.[2]

Works

- Declaración y uso del reloj español (1549)

- Edition and commentary of Angelo Poliziano, Angeli Politiani: Sylvæ, nutricia, manto, rusticus, ambra illustratum per Franciscum Sanctium Brocensem, Salmanticæ: excudebat Andreas a Portonariis, 1554.

- De arte dicendi (1556)

- Edition and commentary of the Emblemata by Alciati: Comment. in And. Alciati Emblemata: nunc denuò multis in locis accurate recognita et quamplurimis figuris illustrata Lugduni: apud Guliel. Rouillium, 1573.

- Comentarios to the work by Garcilaso de la Vega (1574)

- Edition of Pomponii Melæ De situ orbis (1574)

- Organum dialectum et rethoricum cunctis discipulis utilissimum et necessarium (Lyon, 1579)

- Sphera mundi ex variis auctoribus concinnata (1579)

- Paradoxa (1581)

- Grammaticæ Græcæ compendium (1581)

- Comentarios to the work by Juan de Mena (1582)

- Minerva sive de causis linguæ Latinæ (Salamanca: Renaut, 1587)

- Veræ brevesque Latinæ institutiones (1587)

- De nonnulis Porphyrii aliorumque in dialectica erroribus (1588)

- Edition of the Bucolics by Virgil (1591)

- Edition and commentary of the Ars poetica by Horace: In Artem Poeticam Horatii Annotationes, Salmanticæ: Apud Joannem & Andream Renaut, fratres, 1591.

- Arte para saber latín (1595)

- Edition and commentary of Auli Persii Flacci Saturæ sex: cvm ecphrasi et scholiis Franc. Sanctij Brocen. Salmanticæ: apud Didacum à Cussio, 1599.

- Doctrina de Epicteto (1600)

References

- IJsewijn, Jozef, Companion to Neo-Latin Studies. Part I. History and Diffusion of Neo-Latin Literature, Leuven University Press, 1990, p. 109.

- There are copies of the Inquisition's proceedings against Francisco Sánchez in the Colección de documentos inéditos para la historia de España, vol. II.

Further reading

- Diccionario de literatura española, Madrid: Revista de Occidente, 1964 (3.ª ed.)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Francisco Sánchez de las Brozas |

- Portrait of Francisco Sánchez de las Brozas with an epitome about his life included in the book Retratos de Españoles ilustres, published in 1791.

- Bilingual edition and study of the Minerva by el Brocense