Great James Street

Great James Street is a street in the Bloomsbury district of the London Borough of Camden. It has strong literary and publishing connections, and former residents include the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne and the detective story writer Dorothy L. Sayers. The Nation & Athenaeum, chaired by John Maynard Keynes, and the Nonesuch Press were both based in the street. The street has almost all its original buildings with minimal external changes. It is described in Nikolaus Pevsner's guide as "a gem" and its mostly terraced houses as "unusually uniform for their date".[1] The majority of the street is listed by Historic England.

Street cartouche dated 1721 and the former home of Dorothy L. Sayers at No. 24 | |

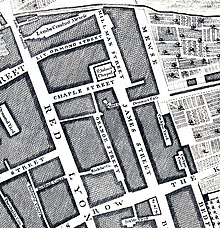

Vicinity of Great James Street (centre, vertical) | |

| Area | Bloomsbury, London |

|---|---|

| Postal code | WC1 |

| Coordinates | 51.52179°N 0.11717°W |

| Construction | |

| Completion | c.1721 |

| Other | |

| Known for | Literary connections |

Location

Great James Street is the continuation of Bedford Row north of Theobalds Road in the Bloomsbury district of the London Borough of Camden. It joins Rugby Street and Millman Street in the north but is pedestrianised beyond the turning for Northington Street on its eastern side.[2]

History and buildings

A cartouche on number 16 dates Great James Street to 1721.[1] The street was named after James Burgess who worked with George Brownlow Doughty and his wife Frances Tichborne in the development of the area including the eponymous Doughty Street.[3]

On John Rocque's map of 1746 it was named just James Street and Northington Street was named Dennis's Passage before it became fully built up. James Court once existed opposite Dennis's Passage.[4] It was James Street too in John Lockie's gazetteer of 1813 but by then Dennis's Passage had become Little James Street.[5] In 1799, Richard Horwood's map showed the streets as Great and Little James Street respectively.[6]

The street has almost all its original buildings with minimal external changes. It is described in Pevsner's guide as "a gem" and its mostly terraced houses as "unusually uniform for their date".[1] The majority of the buildings are listed by Historic England at grade II or II* level. The architecture is in the Georgian style with the exception of Millman Place, a post-war development on the east side at the north end that extends into Millman Street via a second floor pedestrian bridge.[1]

At the north end on the western side on the corner with Rugby Street is the grade II listed The Rugby Tavern.[7]

Literary connections

The street has strong literary and publishing connections and former residents include:

- Novelist and poet George Meredith lived at No. 26 in the 1840s.[8]

- The poet Algernon Charles Swinburne lived at No. 3 in the 1870s.[8]

- Critic and friend of Swinburne, Theodore Watts Dunton, lived at No. 15 in 1872/73.[8]

- Detective story writer Dorothy L. Sayers lived at No. 24 from 1921 to 1929.

- Author and critic Frank Swinnerton lived at No. 4.[8]

- Humorist, poet, and playwright E. V. Lucas lived at No. 5.[8]

- The Nation & Athenaeum, chaired by John Maynard Keynes[9] and described as "the mouthpiece of Bloomsbury liberalism",[10] was published from No. 38 in the 1920s.[9] It eventually merged and became the New Statesman.[10]

- The Nonesuch Press was based in the street from 1924 to 1936.[11]

- Sinologist Arthur Waley lived at No. 22 in the 1960s.[8]

- The Paternoster Press, publishers of Christian literature, were at No. 11 until 1962.[12]

Other former residents

- The surveyor Thomas Browne had his town house in the street and died there in 1780.[13]

- The surveyor Alfred Bailey and architect William Wood Deane were in partnership at No. 13 in the early 1850s.[14]

References

- Pevsner, Nikolaus & Bridget Cherry. (2002). The Buildings of England: London 4 North. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. p. 312. ISBN 0300096534.

- Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- Bebbington, Gillian. (1972) London Street Names. London: B.T. Batsford. pp. 112-113. ISBN 0713401400

- Hyde, Ralph. (1982) The A to Z of Georgian London. London: London Topographical Society. p. 7. ISBN 0902087169

- London Topographical Society. (1994) Topography of London: Facsimile of John Lockie's Gazetteer 1813. London: London Topographical Society. Map. ISBN 0902087398

- Laxton, Paul & Joseph Wisdom. (1985) The A to Z of Regency London. London: London Topographical Society. p. 7. ISBN 0902087193

- Historic England. "Rugby Public House (1271397)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- Williams, George G. Assisted by Marian and Geoffrey Williams. (1973) Guide to Literary London. London: Batsford. p. 249. ISBN 0713401419

- The Nation and Athenæum, Vol. 41, 17 September 1927, p. 1.

- About the New Statesman. New Statesman. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- "Great James Street" in Christopher Hibbert; Ben Weinreb; John Keay; Julia Keay. (2008). The London Encyclopaedia (3rd ed.). London: Macmillan. p. 342. ISBN 978-0-230-73878-2.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- The Bookseller, 1962, p. 1372.

- Browne, Thomas. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 9 July 2020. (subscription required)

- Deane, William Wood. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 9 July 2020. (subscription required)

External links