Doughty Street

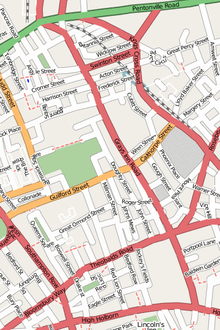

Doughty Street is a broad tree-lined street in the Holborn district of the London Borough of Camden. The southern part is a continuation of the short John Street, which comes off Theobald's Road. The northern part crosses Guilford Street and ends at Mecklenburgh Square. The street is named after a landlord of the area at the time it was built, Henry Doughty.[2]

| |

| |

| Length | 0.1 mi[1] (0.2 km) |

|---|---|

| Location | Camden, London |

| Postal code | WC1 |

| Nearest Tube station | |

| south end | Roger Street 51.5229°N 0.1160°W |

| north end | Mecklenburgh Square 51.5248°N 0.1176°W |

| Construction | |

| Construction start | 1790 |

History

The street contains mainly grade II listed Georgian houses built between 1790 and the 1840s. Many of the houses have been converted into offices and are popular with companies in the legal profession and the media. In the last few years, many of these have been converted back to family homes.

In the nineteenth century, it was an exclusive residential street and had gates at either end to restrict entry and these were manned by porters.[3]

"It was a broad, airy, wholesome street – none of your common thoroughfares, to be rattled through by vulgar cabs and earth-shaking Pickford's vans; but a self-included property, with a gate at each end, and a lodge with a porter in a gold-laced hat and the Doughty arms on the buttons of his mulberry coat, to prevent any one, except with a mission to one of the houses, from, intruding on the exclusive territory."[4]

The London Post Office Railway passes underneath the street, but is now disused.

Notable occupants

- A notable resident of Doughty Street was Charles Dickens. On 25 March 1837, Dickens moved with his family into No. 48 (on which he had a three-year lease at £80 a year) where he would remain until December 1839. He wrote Oliver Twist in the house. His sister-in-law, Mary Hogarth died here. This address is now a grade I listed building and has housed the Charles Dickens Museum since 1925.[3]

- Novelist and dramatist, and friend of Charles Dickens, Edmund Yates lived at No. 43 in the 1850s and recorded memories of the house and street in his memoirs.[5]

- Authors Vera Brittain and Winifred Holtby shared a flat at No. 58 in the 1920s and earlier Sydney Smith lived at No. 14.[6]

- The poet Charlotte Mew was born at No. 30 in 1869 and lived there until 1890.

- The novelist and writer E. M. Delafield occupied a flat on the street, and it serves as the setting for several entries in her pseudo-autobiographical works 'The Provincial Lady Goes Further' and 'The Provincial Lady in America'.

- Doughty Street Chambers (No.10-11 & 53–54). This prominent Human Rights Chambers have occupied property on the street since opening its doors for business for the first time in 1990. Starting with only 30 members, they now have 100 barristers.

- The Spectator, a conservative magazine was based at No. 55 for many years until moving to new premises.

- 18 Doughty Street (Doughty Media Ltd.), a conservative internet site.

- Sir Travers Humphreys, the eminent judge, was born here in 1867.

- The British Thoracic Society, a medical professional body are at No. 17.

- The UK office of the US educational charity the Fulbright Commission is based at No. 62.

- The literary agency, Sheil Land Associates, is based at No. 52, having previously been based at No. 43. Their post is often still delivered to their old address.

References

- "Driving directions to Doughty St". Google. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- Weinreb, Ben & Hibbert, Christopher (1992). The London Encyclopaedia (reprint ed.). Macmillan. p. 241.

- "Dickens House Museum". Archived from the original on 1 April 2007.

- Page 181, "Edmund Yates, His Recollections and Experiences" 1885 Richard Bentley & Son.Works by/about Edmund Yates, at Internet Archive

- Page 181, "Edmund Yates, His Recollections and Experiences" 1885 Richard Bentley & Son.

- "English Heritage". www.english-heritage.org.uk.