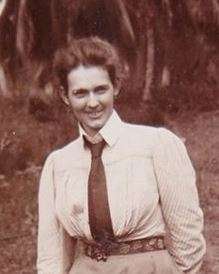

Grace Schneiders-Howard

Grace Schneiders-Howard (16 September 1869 – 4 February 1968) was a Surinamese social worker and politician. Initially beginning her career in civil service as an agent for immigrant workers, she later worked in the Hygiene Department to develop sanitation services in the country. When women were allowed to run for office, but without the right to vote, she ran as a candidate for the Estates of Suriname. Elected in 1938, she became the first woman to serve in the Surinamese legislature. A controversial and abrasive figure, Schneiders-Howard was convinced of her own racial and social superiority, using her work with migrants and the poor to propel her own aims and views of how society should be organized. A pioneer woman in many fields, she was condemned by her opponents, who questioned her morals, her motivations and even her sanity. Her lasting impact was upon bringing improved sanitation of the country.

Grace Schneiders-Howard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Grace Ruth Howard 16 September 1869 |

| Died | 4 February 1968 (aged 98) |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Other names | Grace Ruth Schneiders, Gay Howard |

| Occupation | social worker, politician |

| Years active | 1911–1946 |

| Known for | establishing public drainage, sewage and water supply systems in Suriname |

Early life

Grace Ruth Howard, known as "Gay" was born on 16 September 1869 in Paramaribo, capital of the Dutch Colony of Surinam to Helena Sophia (née van Emden) and Alfred Ernest Howard. Her father was a plantation owner, originally from Barbados and her mother was from the upper-echelons of the Surinamese Jewish community.[1] Her parents divorced when Howard was two years old[2] and she and her mother moved to The Hague, where part of her family lived.[1] Howard recalled her childhood as privileged, noting she rode in carriages to school; however, her father, whose business was impacted by the abolition of slavery in 1863 faced financial difficulties.[3] Howard wanted to become a doctor, but her parents prohibited the career choice.[2] During her schooling, she became politically active and attended meetings of the socialist party. After completion of her studies, in 1893 in Dover, England, she married Wilhelm Schneiders, a German headmaster who had been living in Aachen and they subsequently had three children: Helen (1895–1982), Charles (1896–1989) and Erna (1898–1935).[1]

Career

In 1902, Schneiders-Howard and her family moved back to Suriname, where her husband began working as a bookbinder.[1] She wanted to missionize at the prisons, but her plan was rejected. Turning her sights to cleaning up the city, she initially worked as a yard cleaner and then worked for a garbage collection service.[4] Her husband suffered from a bone-marrow illness and was hospitalized for it. During his confinement, Schneiders-Howard took up with a French deportee from French Guiana and had a fourth child Hendrik (also known as Hein, 1908–1974) with him in 1908.[5][1] Police reports from the time described her as a woman of dubious reputation[5] and the governor called her morality into question in a letter to the colonial minister about her affair with the Frenchman.[6]

In 1911, she founded an association called Ikhtiyar aur Hakh (Freedom and Law) to assist Indo-Caribbean workers in enforcement of their rights under their labor contracts.[1] During this period in the Dutch West Indies, many contract workers from India and Southeast Asia were brought to the colonies as indentured laborers.[7] A similar organization, the Surinamese Immigrants' Association had been founded by Sital Persad, a Hindi interpreter with close ties to the colonial government.[1] In part, because she felt she was socially and racially superior to Persad and in part because she believed she knew what was best for the Asian migrants and African laborers, Schneiders-Howard's organization helped workers enforce their rights, while simultaneously ensuring that they remained at the bottom of the social hierarchy and in the rural areas of the country.[8] Accusing Persad of fraud,[1] he filed criminal charges against her for disparaging his reputation. In one of the few cases in Surinamese legal history of defamation, Persad won his case and Schneiders-Howard was sentenced to two months in jail.[9] Leniency was asked, but because the courts were unconvinced of her regret, Schneiders-Howard served her entire sentence.[1]

In 1915, the Colonial Governor of Suriname contracted with the U.S.-based Rockefeller Foundation's International Health Commission to eradicate hookworm disease in the country.[10] Migrant workers with no immunity to local disease had been widely affected by malaria and hookworm, which cause an inability to work, though was not often fatal.[4][11] Schneiders-Howard was employed by the foundation in its attempts to improve hygiene by constructing latrines and education.[1] Initial reports on the program proved an 83% success rate of treating patients and curing the disease, but increasingly laborers, planters and government officials thwarted the efforts of the program. Neither the Surinamese authorities nor the Dutch government were willing to spend their own funds to assist in implementation, insisting that the foundation had adequate funds. Migrants were convinced that the medicine was poison or a potion which could force them to convert to Christianity and planters simply wanted their laborers to work, healthy or not.[12] In 1917, the director of the program returned to the United States on temporary leave and did not return until 1921.[13] Schneiders-Howard wrote numerous letters to the government authorities in both the colony and The Hague, urging them to bring the Foundation back,[14] and in the meantime continued their work on behalf of the Surinamese government.[1]

In 1919, Schneiders-Howard became an employee on a contingency basis for the sanitation department. Within two years, she was promoted to temporary sanitation inspector. An ordinance was passed, in 1923, to enforce hookworm controls and appoint sanitary inspectors who had been trained by the Rockefeller foundation. The following year, Schneiders-Howard was made Chief Sanitation Inspector, becoming the highest ranking woman employee in the colonial administration.[15] Her duties included inspecting latrines, rubbish and weeds in Paramaribo and the surrounding plantations and settlements.[14] Imposing fines for failure to build latrines or keep them clean, Schneiders-Howard worked around ten hours per day inspecting 150 plots of land.[16] Dismissed for her outspoken disagreement with her superiors and officials in 1930, she was reinstated in 1933.[15] Not content with pressing for financial support from officials to deal with public health issues and construction of the drainage and sewage system,[14] Schneiders-Howard saw rainwater collection as a breeding ground for mosquitoes, which carried the yellow fever virus, among other diseases.[16] She was instrumental in bringing a water supply system to Paramaribo in 1933 and simultaneously blocking wells and removing all open collection vessels.[14][16] In 1937, she was again fired from her position for insubordination to her superiors.[15]

Though not a feminist nor a suffragist who fought for women's right to vote, Schneiders-Howard was quick to take advantage of the opportunity when women were first allowed to run for office in 1936. Asians, workers and women did not have enfranchisement, but when she ran and was elected in 1938, Schneiders-Howard became the first woman to serve in the Estates of Suriname, as the legislature was called at that time. Her areas of interest, while in office, were on the cost of living, wages and working conditions; public health, clean water and sanitation; small agriculture; and road conditions. She staunchly supported Dutch rule,[17] was not in favor of changing governance from the colonial system,[18] and was fervently against Nazism.[17] As she had in her previous civil service position, Schneiders-Howard often clashed with her male colleagues, personally attacking them and their positions. In one case, she falsely accused a prominent businessman of burning a Dutch flag.[17] These types of behaviors made her a controversial figure, praised by some for her well-informed, trustworthy, willingness to work[17] and belittled by others for her failure to behave as a respectable woman.[19] After one term, she was not returned to parliament, though she ran again in 1942, 1943, and 1946.[17]

Death and legacy

Schneiders-Howard died on 4 February 1968 in Paramaribo. At the time of her death, she was most remembered for her efforts in public health but is most often cited in the present as the first woman legislator of Suriname. A postage stamp of Suriname bears her likeness, a school in the Nickerie District was named in her honor, and a street in Paramaribo carries her name.[1]

References

Citations

- Hoefte 2017.

- Hoefte 2007, p. 85.

- Hoefte 2007, pp. 85–86.

- Hoefte 2007, p. 87.

- Hoefte 2007, p. 94.

- Hoefte 2007, p. 98.

- Hoefte 2007, p. 86.

- Hoefte 2007, p. 97.

- Jadnanansing 2015.

- Hoefte 2010, p. 211.

- Hoefte 2010, p. 213.

- Hoefte 2010, pp. 215–216.

- Hoefte 2007, p. 89.

- Hoefte 2010, p. 220.

- Hoefte 2007, p. 90.

- Hoefte 2007, p. 91.

- Hoefte 2007, p. 93.

- Hoefte 2007, p. 96.

- Hoefte 2007, p. 95.

Bibliography

- Hoefte, Rosearijn (2010). "10. The Difficulty of Unhooking the Hookworm". In De Barros, Juanita; Palmer, Steven; Wright, David (eds.). Health and Medicine in the circum-Caribbean, 1800–1968. New York, New York: Routledge. pp. 211–226. ISBN 978-1-135-89482-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hoefte, Rosemarijn (6 March 2017). "Howard, Grace Ruth (1869-1968". Huygens ING (in Dutch). University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands: Digitaal Vrouwenlexicon van Nederland. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hoefte, Rosemarijn (Fall 2007). "The Lonely Pioneer: Suriname's First Female Politician and Social Activist, Grace Schneiders-Howard". Wadabagei. Brooklyn, New York: Caribbean Diaspora Press. 10 (3): 84–103. ISSN 1091-5753. Retrieved 28 October 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Jadnanansing, Carlo (21 December 2015). "Denigrerende uitlatingen jegens een politiek leider" [Denigrating statements against a political leader] (in Dutch). Paramaribo, Suriname: Star Nieuws. Archived from the original on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)