Gong Kai

Gong Kai (simplified Chinese: 龚开; traditional Chinese: 龔開; pinyin: Gōng Kāi; Wade–Giles: Kung K’ai; 1222–1307) was a Chinese government official during the last years of the Song Dynasty. The latter part of the Song Dynasty, in which Gong Kai lived, is known as the Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279). After the fall of the Song Dynasty to the Yuan Dynasty, he became what was known as a scholar-amateur painter. The artists of the Song were mostly influenced by momentary and sporadic pleasures and beauty. However, there is no evidence that Gong Kai painted during this period. Instead, most paintings attributed to Gong Kai are from Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368).

Life in the Southern Song Dynasty

Gong Kai was born in Huaiyin in present-day Jiangsu Province in 1222. His courtesy name was Shengyu (圣予) and his pseudonym was Cuiyan (翠岩). As was traditional in the Song Dynasty, Gong Kai received the standard classical education. As a boy, his teachers saw that he showed great potential in painting, poetry, and calligraphy. Unfortunately, Gong Kai failed to pass the examinations necessary to become a high-ranking government official. During the Song Dynasty (960-1279), Gong Kai served the Song government as a minor official in the Board of Salt Revenues. To some extent, he also served as a general’s secretary prior to the invasion of the Mongols.

Life under the Mongol Rule

In 1271, Kublai Khan and the Mongols began assembling the oppressed Chinese people of the Song Dynasty to rise up against the current government. Over several years, he successfully brought the Song Dynasty to an end in 1279 with the Battle of Yamen and established the Yuan Dynasty, also called Da Yuan. The Mongols offered government positions to some servants of the Song Dynasty because they wanted to employ certain aspects of the previous government. However, it was unlikely that they would have asked Gong Kai. Even though he had previously served under the former government, Gong Kai, being from Southern China, was now at the bottom of the social hierarchy under the Mongol Rule.

As a Song loyalist, Gong Kai could not work under the new government. He and many other loyalists became i-min. An i-min was literally a “left-over subject” who chose to live a life of exile. Without a productive method of protest, the i-min turned to forms of symbolic protest, such as their paintings. Quite frequently, they would meet and write poetry about their losses due to the fall of the Song Dynasty. After the defeating of the Song, Gong Kai fled to Hangzhou on the Yangtze River where he would spend his time writing and painting. He used his paintings as a medium of expression for his thoughts of the new government. This is most reflected in the painting Jun Gu a Noble Horse. Without his government job, Gong Kai’s family became extremely impoverished. The only sources of income to the family were the sale of Gong Kai’s paintings and calligraphy and the occasional trade for essential goods. Some accounts even suggest that Gong Kai was not able to afford a table and instead laid the paper on his son’s back to paint.

Paintings

Paintings from the Yuan Dynasty were unlike any others produced in previous eras in China. Due to the Mongol seizure of the Song Dynasty and the difficult economic state, the existence of many professional art schools and painters in China began to decline. Now, fewer artists were working for the imperial courts or other wealthy sponsors. This led to the rise of the preexisting class of scholar-amateur painters, like Gong Kai.

Since he was not a trained professional painter, Gong Kai's style of painting could be described as amateur in appearance and straightforward. Some scholars believe that reason for his style was due to his appearance. He was reported as being an "imposing figure," very tall and with a long beard. They feel that his rough looks caused his brushwork to be coarse and added the “oddness of the images in his paintings."

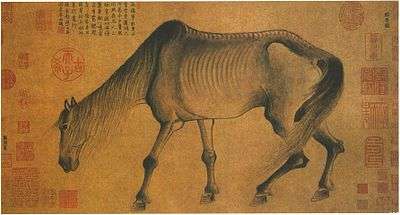

Jun Gu a Noble Horse

Jun Gu a Noble Horse is Gong Kai’s most famous painting. This Yuan Dynasty painting was created using ink on a paper hand scroll. Horses were considered a specialty of Gong Kai, specifically those drawn in the style of the Tang Dynasty. In fact, Gong Kai’s Jun Gu a Noble Horse very closely resembles the painting Night-Shining White by Han Gan in the Tang Dynasty. Chou Mi, a Song Dynasty scholar and acquaintance of Gong Kai, said that Gong’s horses were "flying like the wind, with misty manes and warlike bones, muscles supple as orchid leaves – truly endowed with all he noble attributes".

The animal is probably meant to be from the Song Dynasty (even though drawn in the Tang Dynasty style). In previous years, this horse had been a noble, lively, and youthful creature, but now is reduced to a mere skeleton, clutching onto the last pieces of his shattered dignity. One possibility is that the horse is a symbol for the devastated Song Dynasty. Another possibility is that the horse represents Gong Kai and other scholars like himself (especially since horses during this time period generally were used as a metaphor for humans). To Gong Kai, Jun Gu a Noble Horse is an i-min just like himself.

A poem associated with the painting reads:

“Ever since the clouds and mist fell upon the Heavenly Pass, Empty have been the twelve imperial stables of the former dynasty. Today who will have pity for the shrunken form of his splendid body? In the light of the setting sun, on the sandy bank, he casts his towering shadow – like a mountain!”[1]

Zhong Kui Traveling

Gong Kai’s second most famous work of art is Zhong Kui Traveling, also from the Yuan Dynasty. It is sometimes referred to as Zhong Kui Traveling with his Sister. In the painting, Zhong Kui and his sister are being carried in “palanquins” by several demons. Towards the back of the processional, nine more demons are carrying luggage and other items. The demons are pictured as gangly, grotesque creatures wearing only loin clothes and hats. Some are barely more than skin and bones. The hand scroll containing the painting is over one and a half meters long.

When Zhong Kui originated, he was basically a god of folklore legends who prevailed over ghosts and controlled demons. According to legend, Emperor Minghuang of the Tang Dynasty claimed that Zhong Kui first appeared to him in a dream. In the dream, the emperor watches Zhong Kui slay the demon that had stolen from the emperor. The emperor immediately told his court artist, who then painted a portrait of Zhong Kui by the description given to him. Since then, thousands of pictures of Zhong Kui have been produced. Most often these pictures are painted above entrances to houses and businesses to ensure that Zhong Kui protect them from demons.

However, the paintings occasionally take on a different and more political meaning. This is the case with Gong Kai’s painting. As a loyalist of the Song Dynasty, Gong Kai probably used this painting as a way of expressing that he longed for a being like Zhong Kui to chase the Mongols, or “demons,” out of the country. The calligraphy accompanying the hand scroll indirectly supports this interpretation.

The Captivity of Cai Wenji and Wenji’s Return to China

Though it is not known for certain, the paintings The Captivity of Cai Wenji and Wenji’s Return to China are believed to have been painted by Gong Kai. These were both painted using ink on paper. Both paintings are kept at the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

Cai Wenji was born at the end of the second century, during the Han Dynasty. After two years of marriage, Cai Wenji’s husband died and she returned to Chenliu, the city of her birth. Once there, she was captured by the Xiongnus' army and forced to marry Zuoxian, a Xiongnu chief, with whom she had two sons. Twelve years passed before the new prime minister and friend of her father, Cao Cao, sent out a search party with brides for Zuoxian in return for Cai Wenji.

According to some scholars, Gong Kai painted Wenji’s Return to China. However, the style of the painting is so different from Gong Kai’s usual style that no one knows for certain if he is its artist. Nonetheless, scholars attribute this painting to Gong Kai because of knowledge of an illustrated Cai Wenji story done by him. This painting and a similar one, The Captivity of Cai Wenji, are possibly part of that story.

Other Paintings

There are other paintings that experts believe may have been painted by Gong Kai. Still, only Emaciated Horse and Zhong Kui Traveling are known for certain to be Gong Kai's works. Several other possible paintings of his are the hanging scrolls titled The Three Stars, Searching for Plum Blossoms by Boat, and Fishing with Cormorants.

Poetry

Aside from his paintings, Gong Kai is also known for his poetry. His most famous poem is "宋江三十六人赞". His only surviving book is "龟城叟集".[2]

Notes

- Chinese text: "一從雲霧降天關,空盡先朝十二閑。今日有誰憐瘦骨,夕陽沙岸影如山"

- Cihai: Page 1661.

References

- "Gong Kai." The Concise Grove Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press, Inc., 2002.

- Cahill, James. "The Yuan Dynasty."Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting. 1997.

- Cahill, James. Hills Beyond A River. New York: John Weatherhill, Inc., 1976.

- Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman. "Siyah Qalem and Gong Kai: An Istanbul Album Painter and A Chinese Painter of the Mongolian Period." Muqarnas Volume IV: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture (1987): 59-71. Print.

- Department of Asian Art. "Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279)". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ssong/hd_ssong.htm (October 2001).

- “Cai Wenji - A Brilliant but Stifled Talent." All-China Women's Federation 29 Mar 2007 Web.20 Apr 2009. <http://www.womenofchina.cn/Profiles/Women_in_History/1%5B%5D

- Ci hai bian ji wei yuan hui (辞海编辑委员会). Ci hai (辞海). Shanghai: Shanghai ci shu chu ban she (上海辞书出版社), 1979.