Hanging scroll

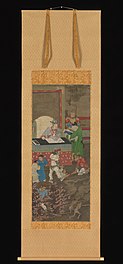

A hanging scroll is one of the many traditional ways to display and exhibit East Asian painting and calligraphy. The hanging scroll was displayed in a room for appreciation; it is to be distinguished from the handscroll, which was narrower and designed to be viewed flat on a table in sections and then stored away again.

| Hanging scroll | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Chinese hanging scrolls on display | |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Chinese | 立軸[1] 掛軸[1] 軸[1] | ||||||

| |||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Quải Trục | ||||||

| Chữ Hán | 掛軸 | ||||||

| Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 족자 | ||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | 掛軸 | ||||||

Hanging scrolls are generally intended to be displayed for short periods of time and are then rolled up to be tied and secured for storage.[2][3] The hanging scrolls are rotated according to season or occasion, and such works are never intended to be on permanent display.[4] The painting surface of the paper or silk can be mounted with decorative brocade silk borders.[3] In the composition of a hanging scroll, the foreground is usually at the bottom of the scroll while the middle and far distances are at the middle and top respectively.[3]

The traditional craft involved in creating a hanging scroll is considered an art in itself.[5] Mountings for Chinese paintings can be divided into a few types, such as handscrolls, hanging scrolls, album leaves, and screens amongst others.[6] In the hanging scroll the actual painting is mounted on paper, and provided at the top with a stave, to which is attached a hanging cord, and at the bottom with a roller.

History

Scrolls originated in their earliest form from literature and other texts written on bamboo strips and silk banners across ancient China.[5][7] The earliest hanging scrolls are related to and developed from silk banners in early Chinese history.[5][8][9] These banners were long and hung vertically on walls.[5] Such silk banners and hanging scroll paintings were found at Mawangdui dating back to the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE).[8][9] By the time of the Tang dynasty (618–907), the aesthetic and structural objectives for hanging scrolls were summarized, which are still followed to this day.[2] During the early Song dynasty (960–1279), the scrolls became well suited to the art styles of the artists,[7][8] consequently hanging scrolls were made in many different sizes and proportions.[5]

Originally introduced to Japan from China as a means of spreading Buddhism, it has found a place in Japanese culture and art and plays an important role in interior decoration.[10]

Description

The hanging scroll provides an artist with a vertical format to display his art on a wall.[3][7] It is one of the most common types of scrolls for Chinese painting and calligraphy.[11] Horizontal hanging scrolls are also very frequently used and a common form.[11] The hanging scroll is different from the handscroll in that the latter is not hung. The handscroll is a long narrow scroll for displaying a series of scenes in Chinese painting.[7][11] This scroll is intended to be viewed section for section during the unrolling and flat on a table,[11] which is in contrast to a hanging scroll that is appreciated in its entirety while guiding the eyes through the artwork.[5][8]

Mounting styles

There are several hanging scroll styles for mounting, such as:

- Yisebiao (一色裱, one color mount)[2]

- Ersebiao (二色裱, two color mount)[2]

- Sansebiao (三色裱, three color mount)[2]

- Xuanhezhuang (宣和裝, Xuanhe style),[2][12] also known as Songshibiao (宋式裱, Song dynasty mount)[12]

Arrangements and formats

Besides the previous styles of hanging scroll mountings, there are a few additional ways to format the hanging scroll.

- Hall painting (中堂畫)

- Hall paintings are intended to be the centerpiece in the main hall.[11] It's usually quite a large hanging scroll that serves as a focal point in an interior and often has a complicated subject.[11]

- Four hanging scrolls (四條屏)

- These hanging scrolls were developed from screen paintings.[11] It features several narrow and long hanging scrolls and is usually hung next to each other on a wall, but can also be hung on its own.[11] The subjects have related themes,[11] such as the flowers of the four seasons, the Four Gentlemen (orchid, bamboo, chrysanthemum, plum blossom), the Four Beauties (ladies renowned for their beauty).

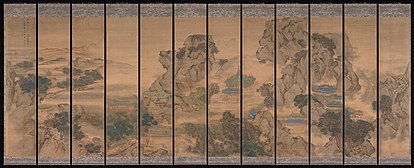

- Panoramic screen (通景屏)

- The panoramic screen consists of several hanging scrolls that have continuous images, in which the subject continues further in another scroll.[11] These hanging scrolls cover large areas of a wall and usually do not have a border in between.[11]

- Couplet (對聯)

- A couplet is two hanging scrolls placed side by side or accompanying a scroll in the middle. These are with poetic calligraphy in vertical writing. This style came to popularity during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).[13]

- Thin strip painting (條幅畫)

- Narrow strip paintings intended for smaller rooms and spaces.

Features and materials

Chinese mounting and conservation techniques are considered a traditional craft and are believed to have developed around 2,000 years ago.[2] This craft is considered an art onto itself.[5] Careful attention was and still is paid to ensure the quality and variety of the silk and paper to protect and properly fit the artwork onto the mounting, as it gives form to the art.[5] The art is fixed onto a four-sided inlay, made from paper or silk, thus providing a border.[5]

The artwork in the middle of the scroll is called huaxin (畫心; literally "painted heart").[1] There is sometimes a section above the artwork called a shitang (詩塘; literally "poetic pool"), which is usually reserved for inscriptions onto the work of art, ranging from a short verse to poems and other inscriptions.[7] These inscriptions are often done by people other than the artist.[7] Although inscriptions can also be placed onto the material of the artwork itself.[8] The upper part of the scroll is called tiantou (天頭; symbolizing "Heaven") and the lower part is called ditou (地頭; symbolizing "Earth").[1][5]

At the top of the scroll is a thin wooden bar, called tiangan (天杆), on which a cord is attached for hanging the scroll.[3] Two decorative strips, called jingyan (惊燕; literally "frighten swallows"), are sometimes attached to the top of the scroll.[2][5] At the bottom of the scroll is a wooden cylindrical bar, called digan (地杆), attached to give the scroll the necessary weight to hang properly onto a wall, but it also serves to roll up a scroll for storage when the artwork is not in display.[2][3][5][14] The two knobs at the far ends of the lower wooden bar are called zhoutou (軸頭) and help to ease the rolling of the scroll.[2] These could be ornamented with a variety of materials, such as jade, ivory, or horn.[5]

Method and processes

Traditional scroll mounters go through a lengthy process of backing the mounting silks with paper using paste before creating the borders for the scroll. Afterwards, the whole scroll is backed before the roller and fittings are attached. The whole process can take two weeks to nine months depending on how long the scroll is left on the wall to dry and stretch before finishing by polishing the back with Chinese wax and fitting the rod and roller at either end. This process is generally called 'wet mounting' due to the use of wet paste in the process.

In the late 20th century a new method was created called 'dry mounting' which involves the use of heat activated silicone sheets in lieu of paste which reduced the amount of time from a few weeks to just a few hours. This new method is generally used for mass-produced artwork rather than serious art or conservation as mounting done this way tends not to be as robust as wet mounting whose scrolls can last for over a century before it requires remounting.

References

- "立軸". National Palace Museum. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- Lee, Valerie; Gu, Xiangmei; Hou, Yuan-Li (2003). "The treatment of Chinese ancestor portraits: An introduction to Chinese painting conservation techniques". Journal of the American Institute for Conservation. 42 (3): 463–477. doi:10.2307/3179868.

- "A Look at Chinese Painting". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- Andrews, Julia F. (1994). Painters and politics in the People's Republic of China: 1949 - 1979. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-520-07981-6.

- Sze, Mai-Mai (1957). The Tao of painting. Taylor & Francis. pp. 62–65. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- Norwich, John Julius (1993). The arts (updated impression ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-19-869137-2.

- Dillon, Michael (1998). China: A historical and cultural dictionary. Richmond: Curzon. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-7007-0439-2.

- "Technical Aspects of Painting". Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- Sullivan, Michael (1984). The arts of China (3rd ed.). London: University of California Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-520-04918-5.

- "Hanging Scroll(2018)". Les Ateliers de Japon.

- Qu, Lei Lei (2008). The simple art of Chinese brush painting. New York: Sterling. pp. 58–9. ISBN 978-1-4027-5391-6.

- "宣和装". National Palace Museum. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- "Approaching "Pride of China": Understanding Chinese Calligraphy and Painting". Chinese Civilisation Centre. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- Spielvogel, Jackson J.; Duiker, William J. (2010). The essential world history, Volume 1: To 1800 (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Wadsworth/Cengage Learning. p. 258. ISBN 978-0-495-90291-1.

External links

- MoreInfo: Formats (Mounting). National Palace Museum. (for a diagram of the components of a hanging scroll)

- Short documentary about how a japanese hanging scroll is being made

_label_stip_sf.jpg)