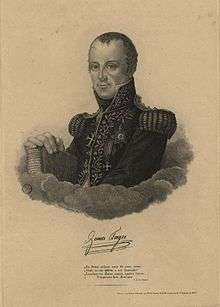

Gomes Freire de Andrade

Gomes Freire de Andrade, ComC (27 January 1757, in Vienna – 18 October 1817) was a field marshal and officer of the Portuguese army who served France at the end of his military career.

Gomes Freire de Andrade | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 27 January 1757 Vienna, Austria |

| Died | 18 October 1817 (aged 60) Oeiras e São Julião da Barra, Portugal |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1782-1814 |

| Rank |

|

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars | Russo-Turkish War War of the Pyrenees War of the Oranges Napoleonic Wars Peninsular War |

| Awards |

|

History

Early life

Gomes Freire de Andrade was the son of Anthony Ambrose Pereira Freire de Andrade e Castro (? – 11 November 1770), Portuguese ambassador to the Austrian court, and his wife Maria Anna Elisabeth, Countess Schaffgotsch (9 October 1738 – November 27, 1787),[1] who was from an old noble family of Bohemia[2] related to the second wife of the Marquis of Pombal.

Freire spent his youth in Vienna, where he received the classical education customarily given to the children of the nobility,[3] excelling in science and mathematics.[4] Whether through his lessons or life experience, Freire became fluent in Portuguese, German and French; and remained devoted to the arts, literature and philosophy throughout his life. His father was an ally of the Marquis of Pombal in his campaign against the Society of Jesus in Portugal, but died in 1770, when Freire was 13 years old, leaving the family in dire straits. Freire was forced to remain in Vienna until he could accumulate funds, then moved to France where he joined the service of the French diplomat Comte de Laforêt for several years before finally achieving his goal of living in Portugal. He went there in February 1781 at the age of 24, having acquired a knighthood in the Order of Christ from the Portuguese government to facilitate the process.[5]

Military service

Destined for a military career from childhood, his father desiring him to have a career in the army[6] and continue the family tradition of military service, Freire joined the Portuguese army as an infantry cadet in September 1782.[7] After completing his training, he was promoted to lieutenant and assigned to the 5th Company of the infantry regiment stationed at Peniche. Freire then went into the Portuguese Royal Navy, embarking in 1784 with an auxiliary squadron sent to assist the Spanish naval forces of Charles III of Spain in the shelling of Algiers. He returned to Lisbon in September, where he was promoted to lieutenant, and in April 1788 volunteered to rejoin the army, and returned to his old regiment with the rank of staff sergeant.

When Russia went to war with Turkey, Freire obtained an appointment to serve in the army of Catherine II and left for St. Petersburg, where he made a favorable impression on the royal court and the empress herself. During the campaign of 1788 – 1789, commanded by Prince Potemkin, Freire served with distinction in the Crimean War, on the plains of the Danube and particularly at the Siege of Ochakov, where he was among the first in his regiment on the front lines when the garrison surrendered on 17 October 1788 after a prolonged siege. Freire was overlooked when decorations were awarded for service in battle, denying him the Order of St. George. He protested, and importuned Colonel Markoff for his due certificates of heroism,[8] leading the empress to reward him with a ceremonial sword and the rank of Colonel of the Imperial Russian Army, which rank was confirmed in absentia by the Portuguese army in 1790.[9]

Later, fighting with the Prince of Nassau's squadron in the naval battle of Svensksund,[10][11] Freire was rescued after Swedish cannons destroyed the "floating battery" he commanded. Although Freire lost his crew, he eventually was decorated with the Order of St. George, one of the most esteemed military orders of Russia; receiving it not from the hands of the empress, as has been said, but from the Prince of Nassau on her behalf. There was gossip at court that Andrade had amorous feelings for the empress, seemingly confirmed by the rise of disagreements between him and Prince Potemkin, known to be her favorite.

Freire returned to Lisbon, where he was assigned to the Marquês das Minas regiment, part of the division Portugal was sending to assist Spain against the French Republic, and about to sail for Catalonia. Having arrived in Lisbon on the eve of the departure of the fleet, Freire did not accompany the expedition by sea, but hurried overland across Spain to take command of the regiment. The Portuguese army arrived in Catalonia with a force of five thousand men under the command of General John Forbes, disembarking at the port of Roses near Barcelona on 11 November 1793. Among the officers of the expedition were foreigners including the Duke of Northumberland, general and peer of England, the Prince of Luxembourg Montmorency, the Count of Chalons and the Count Liautaud. Shortly after arriving at Roses, the Portuguese division left for Céret, while the regiments of Freire de Andrade and Cascais proceeded to occupy the village of Rebós at the front lines. The passage on the road from Roses to Céret having been made during a violent storm, they arrived completely soaked and fatigued by their accelerated march; in spite of this, they soon had to run to the trenches by the bridge over the River Tech at Céret to aid the Spanish army, which already was preparing to attack.[12] Freire's regiment made a brilliant debut in battle, and the French were defeated on 26 November 1793. Freire subsequently pitched camp in Arles, where he set up winter quarters for the Second Brigade. There, according to Latino Coelho, he began to show his restless and undisciplined spirit, "...the haughty courage of the Colonel abrogated full submission and fomented indiscipline throughout the division."[13]

Despite the Spanish-Portuguese army's defeat of the French Republican forces, its campaign in Roussillon would become a trap: the Spanish having 18,000 wounded men in hospital and the Portuguese a thousand men incapacitated, while the French received constant reinforcements. On 29 April 1794, General Dugommier attacked the left flank of the Spanish army, which was made up of units of the Portuguese division. The Portuguese sustained fire from daybreak till two in the afternoon, yet, remarkably, were able to save the day for the Spanish army.

Freire was initiated into Freemasonry before 1785, probably in the Vienna Masonic lodge Zur gekrönten Hoffnung (To Hope Crowned) an organization to which he is known to have belonged together with Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart by 1790, attaining the rank of Worshipful Master of the Regeneration. In 1801 a meeting was held in his home which led to the organization of Portuguese Freemasonry, with the subsequent creation in 1802 of the Grande Oriente Lusitano, the oldest Portuguese Masonic order, of which he became the 5th Grand Master, c. 1815–1817.[14] Freire also belonged to the Portuguese Military Lodge, Chevaliers de la Croix (Knights of the Cross) in Grenoble, between 1808 and 1813.

End of Napoleonic Wars, charges of conspiracy

Having returned to Portugal to join the Portuguese Legion organised by Jean-Andoche Junot and under the command of the Marquis de Alorna, Freire left for France in April 1808, where he was received by Napoleon Bonaparte on 1 June, and subsequently took part in the French invasion of Russia.

Portugal was freed in 1811 of its occupation by French troops with Marshal Masséna's retreat. Following the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815, Freire returned to Portugal in 1817, where he was soon implicated in and accused of leading a conspiracy against the monarchy of King John VI, who, although in exile in Brazil, was still represented by the Regency in mainland Portugal under the British military government of Marshal William Carr Beresford. Freire was arrested, imprisoned, sentenced to death and hanged on 18 October (although he asked to be shot) next to the Fort of São Julião da Barra[15] in Oeiras, for the crime of treason along with eleven other people, including Colonel Manuel Monteiro de Carvalho, the Majors José Campelo de Miranda and Jose da Fonseca Neves and eight army officers.[16] The bodies of Gomes Freire and some of the others were decapitated, burnt, and their ashes thrown into the sea.[17][18] This date was for more than a century a day of mourning in Portuguese Freemasonry, and even today Freire is revered as one of the great Masons and a martyr for liberty, having numerous lodges named after him and many initiates choosing his as their symbolic name.

After the trial and execution of Gomes Freire and other accused conspirators, Beresford sailed to Brazil to request expanded powers over the Portuguese military.[19] He had intended to suspend execution of the sentence until it was confirmed by the sovereign, "but the Regency took offence at the very suggestion, as if sensing an intention to usurp authority, and ordered him in an imperious and arrogant manner to proceed immediately in implementing it."[20]

This action on the part of the Regency and Lord Beresford aroused public protests and intensified anti-British sentiment throughout Portugal, leading to the Liberal Revolution of 1820 (Revolução Liberal) and the fall of Beresford (1820), who was prevented from landing in Lisbon upon his return from Brazil.

Promotion and Units

| French Service to 1814 | |||

| Rank | Unit | Date | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Général de Division | Portuguese Legion | 1810 | |

| 2nd in Command | Portuguese Army under French command | 1807 | |

| Portuguese Service to 1807 | |||

| Rank | Unit | Date | |

| Lieutenant General | 24 May 1807 | ||

| Major General | 20 November 1796 | ||

| Chief | 4th Infantry Regiment of Freire | ||

| Major General graduated | 17 December 1795 | ||

| Colonel | 4th Infantry Regiment of Minas | 8 October 1790 | |

| Major | 13th Infantry Regiment of Peniche | 27 Abril 1788 | |

| Naval Lieutenant | Portuguese Navy | 8 March 1787 | |

| Ensign | 5th Company, 13th Infantry Regiment of Peniche | 9 October 1782 | |

| Cadet | 13th Infantry Regiment of Peniche | 19 September 1782 | |

References

- O Instituto: revista scientifica e literária. Imprensa da Universidade. 1930. p. 277.

- Esteves Pereira (1903). Portugal; diccionario historico, biographico, bibliographico, heraldico, chorographico, numismatico e artistico. J. Romano Torres. p. 505.

- Manuel Barradas (1892). O general Gomes Freire. Typographia Minerva central. p. 11.

- "O Bom senso". 1 (1). 1823: 15–16. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - João Ameal; Rodrigues Cavalheiro (1939). Erratas à História de Portugal de d. João v a d. Miguel. Livraria Tavares Martins. p. 130.

- Raúl Brandão; Gomes Freire de Andrade (1922). 1817, a conspiração de Gomes Freire: quem matou Gomes Freire--Beresford, D. Miguel Forjaz, o principal Souza--Mathilde de Faria e Mello. Editores Renascença Portuguesa. p. 9.

- Raúl Brandão; Gomes Freire de Andrade (1988). Vida e morte de Gomes Freire. Editorial Comunicação. p. 240.

- António Ferrão; Gomes Freire de Andrade (1917). Gomes Freire na Russia. Imprensa da Universidade. p. 175.

- "FerrãoAndrade, 1917, p. 377

- William Guthrie; John Knox; James Ferguson (1801). A New Geographical, Historical, and Commercial Grammar; and Present State of the Several Kingdoms of the World ... Vernon & Hood. p. 150.

- The Scots Magazine. Sands, Brymer, Murray and Cochran. 1790. p. 403.

- Claudio de Chaby, Minister of War of Portugal (1863). Excerptos historicos e collecção de documentos relativos á guerra denominada da Peninsula, e ás anteriores de 1801, e do Roussillon e Cataluña. Resultado da commissão de investigaçoes historicas commettida as capitão de primeira classe Claudio de Chaby, etc. pp. 54–55.

- José Maria Latino Coelho (1891). Historia politica e militar de Portugal: desde os fins do XVIII seculo até 1814. Imprensa Nacional. p. 492.

...e que o animo altivo do coronel, avesso, como era a toda a sujeição, difundia na divisão auxiliar o fermento da indisciplina,...

- Joaquim Gervasio Figueiredo. Dicionário de Maçonaria. Editora Pensamento. p. 356. ISBN 978-85-315-0173-9.

- Joaquim Ferreira de Freitas; Hum portuguez (amigo da justiça e da verdade.) (1822). Memoria sobre a conspiração de 1817: vulgarmente chamada a conspiração de Gomes Freire. Ricardo e Artur Taylor. p. 205.

- Filippe Arnaud de Medeiros (1820). Allegação de facto, e de direito: no processo, em que por Accordão do Juizo da Inconfidencia, e Commissão especialmente constituida, foi nomeado para defender os Pronunciados, como Reos da Conspiração, denunciada em Maio de 1817. Na impressão regia. pp. 5–6.

- Sylvanus Urban (1817). The Gentleman's Magazine: and Historical Chronicle. p. 457.

- Laurentino Gomes (29 August 2013). 1808: The Flight of the Emperor: How a Weak Prince, a Mad Queen, and the British Navy Tricked Napoleon and Changed the New World. Lyons Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-7627-9665-6.

- H. V. Livermore (1947). A History of Portugal. Cambridge University Press. p. 405.

- José Francisco da Rocha Pombo (1953). História do Brasil. W.M. Jackson. p. 12.

mas a Regência melindra-se de semelhante insinuação como se sentisse intuito de diminuir-se-lhe a autoridade, e imperiosa e arrogante, ordena que se proceda à execução imediatamente.

- This article incorporates text translated from a publication now in the public domain: "Portugal; diccionario historico, biographico, bibliographico, heraldico, chorographico, numismatico e artistico", by Esteves Pereira.