Goldbeating

Goldbeating is the process of hammering gold into an extremely thin unbroken sheet for use in gilding.

History

5,000 years ago, Egyptian artisans recognized the extraordinary durability and malleability of gold and became the first goldbeaters and gilders. They pounded gold using a round stone to create the thinnest leaf possible.[1] Except for the introduction of a cast iron hammer and a few other innovations, the tools and techniques have remained virtually unchanged for thousands of years.

Process

Rolling

The karat and color of gold leaf varies depending on the amount of silver or copper added to the gold. Most goldbeaters make 23 karat leaf. The gold and its alloy are put in a crucible and melted in a furnace. The liquid gold is poured into a mold to cast it into a bar. The bar of gold is put through a rolling mill repeatedly. Each time through the mill, the rollers are adjusted closer and closer to each other, to make the gold thinner and thinner. The bar is rolled to a thickness of 25 micrometres (1⁄1000 in).

Beating

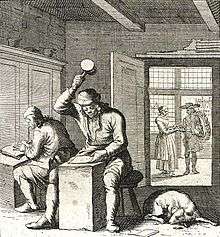

After rolling, the ribbon of gold is cut into one-inch squares. The first step in the beating process is called the cutch.[2] The cutch is made up of approximately 150 skins. In the early days of the trade, ox intestine membrane (Goldbeater's skin) was used to interleave the gold as it was beaten. Today other materials, such as Mylar, are used. Using wooden pincers, the preparer picks up each square of gold and places it in the center of each skin. When the cutch is filled with the small gold squares, it is wrapped in several bands of parchment which serve to hold the packet together during the beating. Parchment is still the best material known to withstand the hours of repeated hammer blows needed to beat the gold.

The gold is beaten on a large, heavy block of marble or granite. These stone blocks were sometimes placed on top of a tree trunk set deep into the ground. This created greater resiliency for the hammer. Beating of the cutch by hand takes about one hour using a fifteen-pound hammer. The goldbeater instinctively follows a pattern and sets up a rhythm, striking the packet with up to seventy strokes a minute. The packet is rotated and turned over to ensure that the gold inside expands evenly in all directions. The original small squares of gold are beaten until they have expanded to the outer edges of the four inch square cutch. The gold is taken out of the cutch and each piece is cut into four pieces with a knife. Using the pincers, these squares of gold are put into a second packet called the shoder, which has approximately 1,500 skins. The shoder is beaten for about three hours until the gold has expanded to a five-inch square.

Packaging

The gold is taken out of the shoder and placed on a leather-covered surface. The gold is thin enough now that the cutter can simply blow on it to flatten it out. Using a wooden implement called a wagon, the gold is quickly cut into four pieces and immediately placed in a packet called a mold for the final beating.[1] The wagon has sharp cutting blades, traditionally made from malacca cane (rattan). The mold contains 1,500 pieces of gold. Before the mold is filled with gold, the skins are coated with a gypsum powder. This process prevents the delicate gold leaf from sticking to the skins.[3] The mold is beaten with an 8-pound (3.6 kg) hammer for three to four hours until it has been beaten into a circle about six inches (15 cm) in diameter. The finished leaf forms an unbroken sheet of gold with a thickness of approximately 100 nanometres (1⁄250000 in). After the leaves are taken out of the mold, they are conventionally cut into a three-and-three-eighths-inch (8.6 cm) square and packaged in tissue-paper books containing twenty-five leaves.

See also

References

- Nicholson, Eric D. (December 1979). "The ancient craft of gold beating". Gold Bulletin. 12 (4): 161–166. doi:10.1007/BF03215119.

- Ward, Gerald W. R., ed. (2008). "Gilding". The Grove Encyclopedia of Materials and Techniques in Art. Oxford University Press. pp. 230–232. ISBN 9780195313918. Retrieved June 30, 2017 – via Google Books.

- Chambers; Patrick, David; Geddie, William (1901). Chambers's encyclopaedia: A dictionary of universal knowledge. p. 283.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Goldbeating. |

- Gold Beating sections from 1903 American Library Edition Of Workshop Receipts Vol5 by Ernest Spon

- Goldschlägerstadt Schwabach (in German) partly illustrated history of goldbeating

- Gold Beating 1959 and Gold Beating Out Takes 1950-1959, two British Pathé newsreel clips depicting the goldbeating process

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.