Lady Godiva

Godiva, Countess of Mercia (/ɡəˈdaɪvə/; died between 1066 and 1086), in Old English Godgifu, was a late Anglo-Saxon noblewoman who is relatively well documented as the wife of Leofric, Earl of Mercia, and a patron of various churches and monasteries. Today, she is mainly remembered for a legend dating back at least to the 13th century, in which she rode naked—covered only in her long hair—through the streets of Coventry to gain a remission of the oppressive taxation that her husband, Leofric, imposed on his tenants. The name "Peeping Tom" for a voyeur originates from later versions of this legend, in which a man named Thomas watched her ride and was struck blind or dead.

Historical figure

Godiva was the wife of Leofric, Earl of Mercia. They had nine children; one son was Ælfgar.[1][2][3][4][5] Godiva's name occurs in charters and the Domesday survey, though the spelling varies. The Old English name Godgifu or Godgyfu meant "gift of God"; Godiva was the Latinised form. Since the name was a popular one, there are contemporaries of the same name.[5][6]

If she is the same Godiva who appears in the history of Ely Abbey, the Liber Eliensis, written at the end of the 12th century, then she was a widow when Leofric married her. Both Leofric and Godiva were generous benefactors to religious houses. In 1043 Leofric founded and endowed a Benedictine monastery at Coventry[7] on the site of a nunnery destroyed by the Danes in 1016. Writing in the 12th century, Roger of Wendover credits Godiva as the persuasive force behind this act. In the 1050s, her name is coupled with that of her husband on a grant of land to the monastery of St. Mary, Worcester and the endowment of the minster at Stow St Mary, Lincolnshire.[8][9][10] She and her husband are commemorated as benefactors of other monasteries at Leominster, Chester, Much Wenlock, and Evesham.[11] She gave Coventry a number of works in precious metal by the famous goldsmith Mannig and bequeathed a necklace valued at 100 marks of silver.[12] Another necklace went to Evesham, to be hung around the figure of the Virgin accompanying the life-size gold and silver rood she and her husband gave, and St Paul's Cathedral in the City of London received a gold-fringed chasuble.[13] She and her husband were among the most munificent of the several large Anglo-Saxon donors of the last decades before the Norman Conquest; the early Norman bishops made short work of their gifts, carrying them off to Normandy or melting them down for bullion.[14]

The manor of Woolhope in Herefordshire, along with four others, was given to the cathedral at Hereford before the Norman Conquest by the benefactresses Wulviva and Godiva—usually held to be this Godiva and her sister. The church there has a 20th-century stained glass window representing them.[15]

Her signature, Ego Godiva Comitissa diu istud desideravi [I, The Countess Godiva, have desired this for a long time], appears on a charter purportedly given by Thorold of Bucknall to the Benedictine monastery of Spalding. However, this charter is considered spurious by many historians.[16] Even so, it is possible that Thorold, who appears in the Domesday Book as sheriff of Lincolnshire, was her brother. (See Lucy of Bolingbroke.)

After Leofric's death in 1057, his widow lived on until sometime between the Norman Conquest of 1066 and 1086. She is mentioned in the Domesday survey as one of the few Anglo-Saxons and the only woman to remain a major landholder shortly after the conquest. By the time of this great survey in 1086, Godiva had died, but her former lands are listed, although now held by others.[17] Thus, Godiva apparently died between 1066 and 1086.[6]

The place where Godiva was buried has been a matter of debate. According to the Chronicon Abbatiae de Evesham, or Evesham Chronicle, she was buried at the Church of the Blessed Trinity at Evesham, which is no longer standing. According to the account in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, "There is no reason to doubt that she was buried with her husband at Coventry, despite the assertion of the Evesham chronicle that she lay in Holy Trinity, Evesham."[6] Her husband was buried in St Mary's Priory and Cathedral in 1057.

William Dugdale (1656) says that a window with representations of Leofric and Godiva was placed in Trinity Church, Coventry, about the time of Richard II.[18]

Legend

.jpg)

The legend of the nude ride is first recorded in the 13th century, in the Flores Historiarum and the adaptation of it by Roger of Wendover. Despite its considerable age, it is not regarded as plausible by modern historians,[20] nor is it mentioned in the two centuries intervening between Godiva's death and its first appearance, while her generous donations to the church receive various mentions.

According to the typical version of the story,[21][22] Lady Godiva took pity on the people of Coventry, who were suffering grievously under her husband's oppressive taxation. Lady Godiva appealed again and again to her husband, who obstinately refused to remit the tolls. At last, weary of her entreaties, he said he would grant her request if she would strip naked and ride on a horse through the streets of the town. Lady Godiva took him at his word, and after issuing a proclamation that all persons should stay indoors and shut their windows, she rode through the town, clothed only in her long hair. Just one person in the town, a tailor ever afterwards known as Peeping Tom, disobeyed her proclamation in what is the most famous instance of voyeurism.[23]

Some historians have discerned elements of pagan fertility rituals in the Godiva story, whereby a young "May Queen" was led to the sacred Cofa's tree, perhaps to celebrate the renewal of spring.[24] The oldest form of the legend has Godiva passing through Coventry market from one end to the other while the people were assembled, attended only by two knights.[25] This version is given in Flores Historiarum by Roger of Wendover (died 1236), a somewhat gullible collector of anecdotes. In a chronicle written in the 1560s, Richard Grafton claimed the version given in Flores Historiarum originated from a "lost chronicle" written between 1216 and 1235 by the Prior of the monastery of Coventry.[26]

Other attempts to find a more plausible rationale for the legend include one based on the custom at the time for penitents to make a public procession in their shift, a sleeveless white garment similar to a slip today and one which was certainly considered "underwear". Thus Godiva might have actually travelled through town as a penitent, in her shift. Godiva's story could have passed into folk history to be recorded in a romanticised version. Another theory has it that Lady Godiva's "nakedness" might refer to her riding through the streets stripped of her jewellery, the trademark of her upper class rank. However, these attempts to reconcile known facts with legend are both weak; in the era of the earliest accounts, the word "naked" is only known to mean "without any clothing whatsoever".[27]

A modified version of the story was given by printer Richard Grafton, later elected MP for Coventry. According to his Chronicle of England (1569), "Leofricus" had already exempted the people of Coventry from "any maner of Tolle, Except onely of Horses", so that Godiva ("Godina" in text) had agreed to the naked ride just to win relief for this horse tax. And as a condition, she required the officials of Coventry to forbid the populace "upon a great pain" from watching her, and to shut themselves in and shutter all windows on the day of her ride.[28] Grafton was an ardent Protestant and sanitized the earlier story.[24]

The ballad "Leoffricus" in the Percy Folio (ca. 1650)[29][30] conforms to Grafton's version, saying that Lady Godiva performed her ride to remove the customs paid on horses, and that the town's officers ordered the townsfolk to "shutt their dore, & clap their windowes downe," and remain indoors on the day of her ride.[31][32]

Peeping Tom

-p20.png)

The story of Peeping Tom, who alone among the townsfolk spied on the Lady Godiva's naked ride, probably did not originate in literature, but came about through popular lore in the locality of Coventry. Reference by 17th-century chroniclers has been claimed,[24] but all the published accounts are 18th-century or later.

According to an 1826 article submitted by someone well versed in local history and identifying himself as W. Reader,[33] there was already a well-established tradition that there was a certain tailor who had spied on Lady Godiva, and that at the annual Trinity Great Fair (now called the Godiva Festival) featuring the Godiva processions "a grotesque figure called Peeping Tom" would be set on display, and it was a wooden statue carved from oak. The author has dated this effigy, based on the style of armour he is shown wearing, from the reign of Charles II (d. 1685). The same writer felt the legend had to be subsequent to William Dugdale (d. 1686) since he made no mention of it in his works that discussed Coventry at full length.[34] (The story of the tailor and the use of a wooden effigy may be as old as the 17th century, but the effigy may not have always been called "Tom". See 1773 date below, and the alternate suggested name "Action".)

W. Reader dates the first Godiva procession to 1677,[35] but other sources date the first parade to 1678, and on that year a lad from the household of James Swinnerton enacted the role of Lady Godiva.[36]

The English Dictionary of National Biography (D.N.B.) gives a meticulous account of the literary sources.[37] The historian Paul de Rapin (1732) reported the Coventry lore that Lady Godiva performed her ride while "commanding all Persons to keep within Doors and from their Windows, on pain of Death", but that one man could not refrain from looking and it "cost him his life"; Rapin further reported that the town commemorates this with a "Statue of a Man looking out of a Window."[38]

Next, Thomas Pennant in Journey from Chester to London (1782) recounted: "[T]he curiosity of a certain taylor overcoming his fear, he took a single peep".[39] Pennant noted that the person enacting Godiva in the procession was not fully naked of course, but wore "silk, closely fitted to her limbs", which had a colour resembling the skin's complexion.[39] (In Pennant's time around 1782 silk was worn, but the annotator of the 1811 edition noted that a cotton garment had since replaced the silk fabric.[39]) According to the D.N.B., the oldest document that mentions "Peeping Tom" by name is a record in Coventry's official annals, dating to 11 June 1773, documenting that the city issued a new wig and paint for the wooden effigy.

There is also said to be a letter from pre-1700, stating that the peeper was actually Action (pronounced Actæon?), Lady Godiva's groom.[40]

Additional legend proclaims that Peeping Tom was later struck blind as heavenly punishment, or that the townspeople took the matter in their own hands and blinded him.[41]

Images in art and society

The Herbert Art Gallery and Museum in Coventry maintains a permanent exhibition on the subject. The oldest painting was commissioned by the County of the City of Coventry in 1586 and produced by Adam van Noort, a refugee Flemish artist. His painting depicts a "voluptuously displayed" Lady Godiva against the background of a "fantastical Italianate Coventry". In addition the Gallery has collected many Victorian interpretations of the subject described by Marina Warner as "an oddly composed Landseer, a swooning Watts and a sumptuous Alfred Woolmer".[24]

John Collier's Lady Godiva was bequeathed by social reformer Thomas Hancock Nunn. When he died in 1937, the Pre-Raphaelite-style painting was offered to the Corporation of Hampstead. He specified in his will that should his bequest be refused by Hampstead (presumably on grounds of propriety) the painting was then to be offered to Coventry. The painting now hangs in the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum.[1]

American sculptor Anne Whitney created a marble sculpture of Lady Godiva, now in the collection of the Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Texas.[42]

Gallery

Marshall Claxton: Lady Godiva (1850), the Herbert, Coventry

Marshall Claxton: Lady Godiva (1850), the Herbert, Coventry Jules Joseph Lefebvre, Lady Godiva, 1891

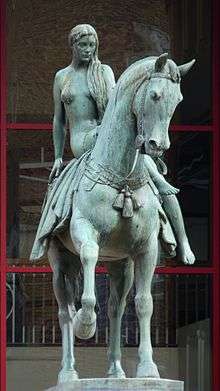

Jules Joseph Lefebvre, Lady Godiva, 1891 Lady Godiva at Maidstone Museum

Lady Godiva at Maidstone Museum Lady Godiva at Herbert Museum

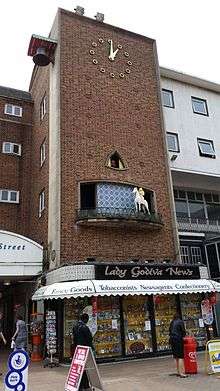

Lady Godiva at Herbert Museum Broadgate Clock, Coventry

Broadgate Clock, Coventry Lady Godiva Statue In Coventry Taken Early 1950s

Lady Godiva Statue In Coventry Taken Early 1950s

References

- Patrick W. Montague-Smith Letters: Godiva's family tree The Times, 25 January 1983

- Samuel Timmins, A History of Warwickshire 1889

- F. Smith ` Warwickshire Delineated' 1820

- Adam Fox 'Oral and Literate Culture in England, 1500-1700' 2000

- P.R. Cross 'Lordship, Knighthood and Locality: A Study in English Society, C. 1180-1280' 1991

- Ann Williams, 'Godgifu (d. 1067?)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edn, October 2006 accessed 18 April 2008 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- "Anglo-Saxons.net, S 1226". Anglo-saxons.net. 13 April 1981. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- "Anglo-Saxons.net, S 1232". Anglo-saxons.net. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- "Anglo-Saxons.net, S 1478". Anglo-saxons.net. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- In the Stow charter, she is called "Godgife" (Thorpe, Benjamin (1865). Diplomatarium anglicum aevi saxonici: A collection of English charters. 1. London: MacMillan. p. 320.)

- The Chronicle of John of Worcester ed. and trans. R.R. Darlington, P. McGurk and J. Bray (Clarendon Press: Oxford 1995), pp.582–583

- Dodwell, C. R.; Anglo-Saxon Art: A New Perspective, 1982, Manchester UP, ISBN 0-7190-0926-X (US edn. Cornell, 1985), pp. 25 & 66

- Dodwell, 180 & 212

- Dodwell, 220, 230 & passim

- "flickr.com". flickr.com. 11 August 2007. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- "Anglo-Saxons.net, S 1230". Anglo-saxons.net. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- K. S. B. Keats-Rohan, Domesday People: A prosopography of persons occurring in English documents 1066–1166, vol. 1: Domesday (Boydell Press: Woodbridge, Suffolk 1999), p. 218

- Dugdale, William (1656). Antiquities of Warwickshire. London.

- Douglas, Alton; Moore, Dennis; Douglas, Jo (February 1991). Coventry: A Century of News. Coventry Evening Telegraph. p. 62. ISBN 0-902464-36-1.

- Coe, Charles (1 July 2003). "Lady Godiva: The Naked Truth". Harvard Magazine. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- Joan Cadogan Lancaster. Godiva of Coventry. With a chapter on the folk tradition of the story by H.R. Ellis Davidson. Coventry [Eng.] Coventry Corp., 1967. OCLC 1664951

- French KL (1992). "The legend of Lady Godiva". Journal of Medieval History. 18: 3–19. doi:10.1016/0304-4181(92)90015-q.

- Lady Godiva, Historic-UK.com

- Marina Warner. When Godiva streaked and Tom peeped The Times, 10 July 1982

- "Lady Godiva (Godgifu)" Archived 22 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Flowers of History, University of California San Francisco

- White, Frances (14 July 2015). "Lady Godiva: Anglo-Saxon noblewoman or Medieval legend?". www.historyanswers.co.uk. Archived from the original on 16 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "The Naked Truth". BBC News. 24 August 2001.

- Grafton 1809, volume 1, p.148. Grafton, Richard (1809). Grafton's chronicle, or history of England: to which is added his table of the bailiffs, sheriffs and mayors of the city of London from the year 1189, to 1558, inclusive : in two volumes. 1. London: P. Johnson. p. 148.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hales, John W.; Furnivall, Frederick J., eds. (1868), "Leoffricus", Bishop Percy's folio manuscript: Ballads and romances, London: Trübner, 3, pp. 477–, pp.473-

- A variant of this ballad is in Collection of Old Ballads (1723–25)

- Hales & Furnivall 1868, 3:473-, vv. 53–60

- DNB 1890 thus was inaccurate in stating that "This ballad first mention the order..", since Grafton had printed it earlier.

- Reader, W. (1826). "Peeping Tom of Coventry and Lady Godiva". The Gentleman's Magazine. 96: 20.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link), ib., "Show Fair at Coventry described". p.22- (with a sketch of Peeping Tom wooden statue)

- Reader 1826, p. 22 "yet no one, including the late Sir W. Dugdale, even hints at the circumstance in question. We may safely, therefore, appropriate it to the reign of Charles II".

- Reader 1826, p. 22 "In 1677 ... the Procession at the great Fair was first instituted."

- Hartland, E. Sydney, Science of Fairy Tales, (1890), p.75, taken down from the Annals of Coventry, ms. D:"31 May 1678, being the great Fair at Coventry.. and Ja. Swinnertons Son represented Lady Godiva"

- DNB 1890, "That one person disobeyed the order ... first stated by Rapin (1732) ... Pennant (Journey from Chester to London)(1782) calls him 'a certain taylor.' The name 'peeping Tom' occurs in the city accounts on 11 June 1773 when a new wig and fresh paint were supplied for his effigy."

- Paul M. Rapin de Thoyras; N. Tindal Thomas (tr.) (1732). The History of England. 1 (2nd ed.). J., J. and P. Knapton. p. 135.

- Pennant, Thomas, The Journey from Chester to London 1811 edition, p.190

- DNB 1890, "Poole quotes from the 'Gentleman's Magazine' a letter from Canon Seward (ca. before 1700) which makes the peeper 'a groom of the countess,' named Action (?Actæon - same name as the figure in Greek mythology who was put to death by being hunted with hounds after seeing the goddess Artemis in her bath)".

- Leman Rede, "Peeping Tom", The New Monthly Magazine and Humorist, (1838), Part the First, p. 115: "Tradition adds, that the people resolved to close up their houses ... but ... that one, whose name has not survived, looked forth upon her, and was stricken blind, as some affirm, by the vengeance of Heaven; or, according to others, was deprived of sight by the inhabitants." (A quote from a source merely identified as "a modern writer".)

- "SIRIS - Smithsonian Institution Research Information System". siris-artinventories.si.edu. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

Further reading

- Sourced and additional bibliography

- Roger of Wendover; Matthew Paris; John Allen Giles (1891). Coxe, Henry O. (ed.). Rogeri de Wendover, Chronica, sive Flores Historiarum. 1. London: H. G. Bohn. pp. 496–7. (A.D. 1057)

- (historic texts)

- Roger of Wendover, Flores Historiarum

- Giles, J. A.; Roger of Wendover (1899), Roger of Wendover's Flowers of History, 1, London: Henry G. Bohn, p. 314(Eng. tr.)

- Matthew Paris

- Yonge, C. D. (1853), The Flowers of History, .. collected by Matthew of Westminster, 1, London: Henry G. Bohn, pp. 544–(Eng. tr.)

- (secondary sources)

- (anonymous), The history of lady Godiva and Peeping Tom of Coventry, with a description, Coventry, J. W. Mills, sixth ed., sans date. books.google(Shows Tom effigy with a bowtie)

- Dugdale, William, Antiquities of Warwickshire (1656)、p. 66 Internet Archive

- Hartland, E. Sydney (June 1890). "Peeping Tom and Lady Godiva". Folk-Lore. I (II): 217–226 – via Google Books.

- Stephen, Leslie; Lee, Sidney, eds. (1890). "Godiva". Dictionary of National Biography. 22. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 36.

- Poole, Benjamin, The History of Coventry (Woodcut of Tom effigy)

- Redgold, Eliza (2015). Naked: A Novel of Lady Godiva. New York: St Martin's Press (Macmillan).

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Lady Godiva |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lady Godiva. |

- Godgifu 2 at Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England

- Cecilia Parsons, "Countess Godiva", 1999, revised 2004: biography and developing legend

- BBC News – the unearthing of a stained glass window identified with Lady Godiva

- James Grout: Lady Godiva, part of the Encyclopædia Romana

- IMDb (2004). "The Bare Witch Project". IMDb.