Godiva Procession

The Godiva Procession is an annual procession in the city of Coventry, England, which re-enacts the story of Lady Godiva. They have been held in Coventry since the 17th century.

History

The first written record of the Godiva Processions is in the Coventry City Annals of 1678. These celebrate and re-enact Godiva's legendary naked ride through Coventry, undertaken to persuade her husband to free the people of the city from the burden of oppressive tolls. Although Godiva certainly existed, the historicity of the ride itself is debated. Godiva, or Godgifu, meaning 'God's Gift', was the wife of Leofric, Earl of Mercia. Apart from references to her donations of land and gifts, there are no mentions to Godiva in contemporary chronicles. The first mention of the ride was over 150 years after her death, and appeared in Wendover's Flores Historiarum in 1190, though this survives only in a fourteenth-century manuscript.[1]

In 1217/18 Henry III granted the Charter for the Great Fair in Coventry, the event with which the Godiva Procession came to be associated. The charter stated that the fair was to begin on the feast day of the Holy Trinity, and continue for eight days.[2] Such a fair would be of great economic benefit to the city and was usually celebrated with a parade by the civic authorities. However, it was over four centuries later that a representative of Godiva was introduced to this procession.

Seventeenth Century

The Coventry Corporation records provide the earliest record of the Godiva Procession:

In this year (1677-8), in the Mayoralty of Mr Michael Earle, there was a new show on the summer, or Great Fair, of followers- that is boys sent out by the several companies, and each Company having new Streamers, and Lady Godiva rode before the Mayor to proclaim the Fair.[2]

The son of James Swinnerton took the part of Lady Godiva in this procession, and a medal was later struck to commemorate the event.[3] By 19th century the Godiva procession was firmly attached to the eight-day-long Coventry Fair. In June 1824, Ann Rollason's Coventry Mercury described the mayor, magistrates and Charter Officers, as well as numerous societies and children following Godiva in procession.[1]

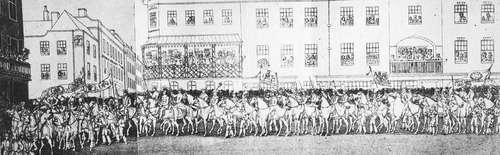

The scale of the procession grew in the following years, and by 1829, the programme describes the order of the procession: led by city guards, St George, bugles and city banners, then Lady Godiva, followed by the civic leaders and staff, numerous bands, Companies such as carpenters and blacksmiths, each with their own banners and followers, then the many Benefit Societies, with their bands and followers. Towards the rear came Woolcombers representing the wool trade in the city, together with the mythical Jason with his Golden Fleece and drawn sword.

Nineteenth Century

The first procession that encouraged the idea of Godiva riding naked was probably in 1842, when she wore a tight fitting, flesh coloured dress, causing fights among spectators trying to get a better view. By 1845, due to complaints about the procession, the Mayor, William Clark, promised to stop the event ‘which has too long disgraced our city’. The Coventry Herald, 25 April 1845, quoted a statement signed by all the main church leaders in the city regretting a proposal ‘during the approaching fair, to get up a procession similar in character to those by which the streets of this City were disgraced in 1842 and 1844’. Despite this, the procession did go ahead that year, and Godiva wore 'a tunic of white satin' and a 'girdle of the same kind' over her flesh coloured dress, with scarves thrown across her shoulders, a mantle, sleeves and a headdress with ostrich feathers.[1] After 1862 processions were held less frequently and did not reach the earlier level of notoriety.[1]

Twentieth Century

For a long time, the names of the women who impersonated Lady Godiva were not made public and by the beginning of 20th Century, an actress was usually employed. Godiva processions were held every three to seven years, and were sometimes organised to celebrate special occasions.[4] In 1902, in the procession marking the coronation of Edward VII, Vera Guedes, from the London Hippodrome, rode as Godiva. To celebrate the coronation of George V in 1911, the actress Miss Viola Hamilton rode in the procession, led for the first time by a nun, with 23,000 school children in the parade, and hundreds more dressed as various historical characters.[5] In 1919, Lady Godiva appeared in the full dress robes of a Saxon countess, with even her horse wearing trousers. This was Miss Gladys Mann, the first Coventry girl to act the role.

The first time a non-actress rode in the procession was in the Coventry Hospital Pageant in 1929, when Muriel Mellerup from Gloucestershire was Lady Godiva.[5]

The first Post war Godiva pageant was in 1951 for the Festival of Britain. There were sixty tableaux illustrating historical and industrial aspects. The organiser, Mr Leonard Turner, obtained 1500 period costumes, for tableaux which included the visit of Henry VII to Coventry in 1500 and a representation of the elephant and castle coat of arms, which included real elephants. The 5-mile-long procession was led by a London student and actress, Ann Wrigg, portraying Lady Godiva, surrounded by the now traditional lines of nuns.[4]

During the second half of the 20th century the Godiva aspect was lost and was replaced by Coventry Carnival. With the loss of the large firms and their apprentice schools in Coventry, this carnival dwindled and eventually ceased. However, in 1997 the Godiva procession was revived and in 2000 Coventry Carnival returned with arts group inspired costumes and tableaux. In 2003 the two combined to become the Godiva Carnival Procession which is associated with the three-day Godiva Festival held in Coventry's War Memorial Park.

References

- McGrory, David (2003). A History of Coventry. Phillimore. ISBN 1-86077-264-1.

- Poole, Benjamin (1869). Coventry: Its History and Antiquities. p. 64.

- Burbidge, F. Bliss (1952). Old Coventry and Lady Godiva. Cornish Brothers Limited. p. 55.

- Newbold, E.B. (1972). Portrait of Coventry. Robert Hale and Company. pp. 193–4. ISBN 0-7091-3194-1.

- McGrory, David (1994). Coventry in Old Photographs. Alan Sutton Publishing Ltd. p. 47. ISBN 0-7509-0674-X.