Glory (novel)

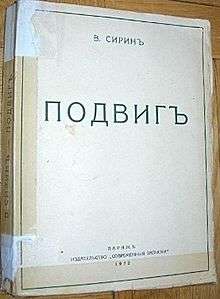

Glory (Russian: Подвиг) is a Russian novel written by Vladimir Nabokov between 1930 and 1932 and first published in Paris.

First edition | |

| Author | Vladimir Nabokov |

|---|---|

| Original title | Podvig |

| Translator | Dmitri Nabokov |

| Language | Russian |

Publication date | 1932 |

Published in English | 1971 |

The novel has been seen by some critics as a kind of fictional dress-run-through of the author's famous memoir Speak, Memory. Its Swiss-Russian hero, Martin Edelweiss, shares a number of experiences and sensations with his creator: goal-tending at Cambridge University, Cambridge fireplaces, English morning weather, a passion for rail travel. It is, however, the story of an émigré family's escape from Russia, a young man's education in England, and his (perhaps) disastrous return to the nation of his birth—the "feat" of the novel's Russian title.

Translation

The text was translated by the author's son, Dmitri Nabokov, with revisions by the author, and published in English in 1971. The Russian title, Podvig, also translates as "feat" or "exploit."[1] Its working title was Romanticheskiy vek (romantic times), as Nabokov indicates in his foreword. He goes on to characterize Martin as the "kindest, uprightest, and most touching of all my young men," whose goal is fulfillment. Nabokov remarks that he has given Martin neither talent nor artistic creativity.

Plot summary

Martin Edelweiss grows up in pre-Revolutionary St. Petersburg. His grandfather Edelweiss had come to Russia from Switzerland, and was employed as a tutor, eventually marrying his youngest pupil. The watercolor image of a dense forest with a winding path hangs over Martin's crib and becomes a leading motif in his life. During Martin's upbringing, his parents get divorced. His father, whom he did not love very much, soon dies. With the revolution, his mother, Sofia, takes Martin first to the Crimea, then out of Russia.

On the ship to Athens, Martin is enchanted by and has his first romance with the beautiful, older poet Alla, who is married. After Athens, Martin and his mother find refuge in Switzerland with his uncle Henry Edelweiss, who will eventually become Martin's stepfather.

Martin goes to study at Cambridge and, on the way, stays with the Zilanov family in London; he is attracted to their 16-year-old daughter, Sonia. At Cambridge, he enjoys the wide academic offerings of the university and takes some time to choose a field. He is fascinated by Archibald Moon, who teaches Russian literature. He meets Darwin, a fellow student from England, who has a literary talent and history as a war hero. Darwin also becomes interested in Sonia, but she rejects his marriage proposal. Martin has a very brief affair with a waitress named Rose, who blackmails Martin by faking a pregnancy, until Darwin unveils her ruse and pays her off. Just before the end of their Cambridge days, Darwin and Martin engage in a boxing match.

Martin does not settle down after Cambridge, to the dismay of his uncle and step-father, Henry. He follows the Zilanovs to Berlin and meets the writer Bubnov. During this period, Martin and Sonia imagine Zoorland, a northern country championing absolute equality. Sonia pushes Martin away, making him feel alienated among the group of friends he had in Berlin. He takes a train trip to the South of France. At some distance he sees some lights in the distance at night, mimicking an episode in his childhood. Martin gets off the train and finds the village of Molignac. He stays there and works a while, identifying himself alternately as Swiss, German, and English, but never Russian. Getting another negative letter from Sonia, he returns to Switzerland. Picking up an émigré publication, Martin realizes that Bubnov has published a story called Zoorland—a betrayal by Sonia, who has become Bubnov's lover.

In the Swiss mountains, he challenges himself to conquer a cliff, ostensibly as a form of training for his future exploits. It becomes clear that Martin has been planning on slipping over the border into Soviet Russia. He meets Gruzinov, a renowned espionage specialist, who knows how to secretly enter the Soviet Union. Gruzinov gives him information, but Martin doubts that Gruzinov is taking him seriously and giving him reliable information.

Preparing for this expedition, Martin says his farewells, first in Switzerland, then back in Berlin, where he meets Sonia, then Bubnov, and then Darwin, who now works as a journalist. He tells Darwin the basics of his plan and enlists his assistance, giving him a series of four postcards to send his mother in Switzerland so she does not get suspicious. Darwin does not believe he is serious. Martin takes the train to Riga, planning to cross from there into the Soviet Union. After two weeks, Darwin gets nervous and follows his friend to Riga. However, Martin is nowhere to be found: he seems to have disappeared. Darwin takes his concerns to the Zilanovs, and then travels to Switzerland to inform Martin's mother of her son's disappearance. The novel ends with Martin's whereabouts unknown and Darwin leaving the Edelweisses' house in Switzerland having delivered the troubling news.

Critical response

Glory was, as the writer and critic John Updike observed in a 1972 New Yorker review, the author's fifth Russian-language novel but his last to be translated to English. "In its residue of bliss experienced," Updike writes, "and in its charge of bliss conveyed, 'Glory' measures up as, though the last to arrive, far from the least of this happy man's Russian novels." [2] In his non-fiction book U & I, the writer Nicholson Baker classes Glory as among his favorites of Nabokov's Russian works.[3] James Wood writes, 'His novel Glory, for instance, is an absolutely ravishing Bildungsroman, but it must be one of the most idea-free novels of its genre in literature. Nabokov writes, of his hero Martin, that “to listen to Moon’s rich speech was like chewing thick elastic Turkish Delight powdered with confectioner’s sugar.” That is rather one’s sweet, obstructive experience of reading a book like Glory. It is a long corridor of intensified sensations.'[4]

References

- Vladimir Nabokov, Glory, New York: Macgraw Hill, 1971. p. v.

- John Updike, "The Crunch of Happiness," The New Yorker February 26, 1972. p. 101.

- Nicholson Baker, U & I, New York: Random House, 1991.

- https://slate.com/culture/1999/04/discussing-nabokov-2.html