Giuseppe Crespi

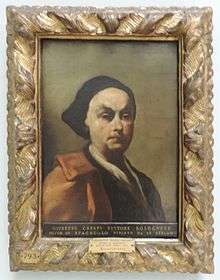

Giuseppe Maria Crespi (March 14, 1665 – July 16, 1747), nicknamed Lo Spagnuolo ("The Spaniard"), was an Italian late Baroque painter of the Bolognese School. His eclectic output includes religious paintings and portraits, but he is now most famous for his genre paintings.

Giuseppe Maria Crespi | |

|---|---|

Self-Portrait c.1700 | |

| Born | 14 March 1665 |

| Died | 16 July 1747 (aged 82) Bologna |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Education | Carlo Cignani |

| Known for | Painting Genre |

Giuseppe Crespi, together with Giambattista Pittoni, Giovan Battista Tiepolo, Giovan Battista Piazzetta, Canaletto and Francesco Guardi forms the traditional great Old Masters painters of that period.

Biography

Crespi was born in Bologna to Girolamo Crespi and Isabella Cospi. His mother was a distant relation of the noble Cospi family, which had ties to the Florentine House of Medici. He was nicknamed "the Spanish One" (Lo Spagnuolo) because of his habit of wearing tight clothes characteristic of Spanish fashion of the time.

By age 12 years, he apprenticed with Angelo Michele Toni (1640–1708). From the age of 15–18 years, he worked under the Bolognese Domenico Maria Canuti. The Roman painter Carlo Maratti, on a visit to Bologna, is said to have invited Crespi to work in Rome, but Crespi declined. Maratti's friend, the Bolognese Carlo Cignani invited Crespi in 1681–82 to join an Accademia del Nudo for the purpose of studying drawing, and he remained in that studio until 1686, when Cignani relocated to Forlì and his studio was taken over by Canuti's most prominent pupil, Giovanni Antonio Burrini. From this time hence, Crespi worked independently of other artists.

His main biographer, Giampietro Zanotti, said of Crespi: "(He) never again wanted for money, and he would make the stories and caprices that came into his imagination. Very often also he painted common things, representing the lowest occupations, and people who, born poor, must sustain themselves in serving the requirements of wealthy citizens". Thus it was for Crespi himself, as he began a career servicing wealthy patrons with artwork. He is said to have had a camera optica in his house for painting.[1] By the 1690s he had completed various altarpieces, including a Temptation of Saint Anthony commissioned by Count Carlo Cesare Malvasia, now in San Niccolò degli Albari.

He journeyed to Venice, but surprisingly, never to Rome. Bearing his large religious canvas of Massacre of the Innocents and a note from Count Vincenzo Rannuzi Cospi as an introduction, Crespi fled in the middle of the night to Florence in 1708, and gained the patronage of the Grand Duke Ferdinand I de' Medici.[2] He had been forced to flee Bologna with the canvas, which while intended for the Duke, had been fancied by a local priest, Don Carlo Silva for himself. The events surrounding this episode became the source of much litigation, in which Crespi, at least for the next five years, found the Duke a firm protector.

An eclectic artist, Crespi was a portrait painter and a brilliant caricaturist, and was also known for his etchings after Rembrandt and Salvator Rosa. He could be said to have painted a number of masterpieces in different styles. He painted few frescoes, in part because he refused to paint for quadraturists, though in all likelihood, his style would not have matched the requirements of a medium then often used for grandiloquent scenography. He was not universally appreciated, Lanzi quotes Mengs as lamenting that the Bolognese school should close with the capricious Crespi. Lanzi himself describes Crespi as allowing his "turn for novelty at length to lead his fine genius astray". He found Crespi included caricature in even scriptural or heroic subjects, he cramped his figures, he "fell in to mannerism", and painted with few colors and few brushstrokes, "employed indeed with judgement but too superficial and without strength of body".[3]

The Seven Sacraments

One celebrated series of canvases, the Seven Sacraments, was painted around 1712, and now hangs in the Gemäldegalerie, Dresden. It was originally completed for Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni in Rome, and upon his death passed to the Elector of Saxony. These imposing works are painted with a loose brushstroke, but still maintain a sober piety. Making no use of hieratic symbols such as saints and putti, they utilize commonplace folk to illustrate sacramental activity.

| The Seven Sacraments | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Crespi and the genre style

Crespi is best known today as one of the main proponents of baroque genre painting in Italy. Italians, until the 17th century, had paid little attention to such themes, concentrating mainly on grander images from religion, mythology, and history, as well as portraiture of the mighty. In this they differed from Northern Europeans, specifically Dutch painters, who had a strong tradition in the depiction of everyday activities. There were exceptions: the Bolognese Baroque titan of fresco, Annibale Carracci, had painted pastoral landscapes, and depictions of homely tradespeople such as butchers. Before him, Bartolomeo Passerotti and the Cremonese Vincenzo Campi had dallied in genre subjects. In this tradition, Crespi also followed the precedents set forth by the Bamboccianti, mainly Dutch genre painters active in Rome. Subsequently, this tradition would also be upheld by Piazzetta, Pietro Longhi, Giacomo Ceruti and Giandomenico Tiepolo to name a few.

He painted many kitchen scenes and other domestic subjects. The painting of The Flea (1709–10)[4] depicts a young woman readying for sleep and supposedly grooming for a nagging pest on her person. The environs are squalid—nearby are a vase with a few flowers and a cheap bead necklace dangling on the wall—but she is sheltered in a tender womb of light. She is not a Botticellian beauty, but a mortal, her lapdog asleep on the bed-sheets.

In another genre scene, Crespi captures the anger of a woman at a man publicly urinating on wall, with a picaresque cat also objecting to the man's indiscretion.

Searching for Fleas

Searching for Fleas Kitchenmaid

Kitchenmaid Dice players

Dice players The Courted Singer

The Courted Singer

Later works and pupils

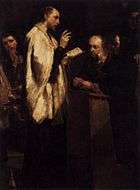

True to his eclecticism, is the naturalistic St John Nepomuk confessing the Queen of Swabia, made late in Crespi's life. In this painting, much is said by partially shielded faces. His Resurrection of Christ is a dramatic arrangement in dynamic perspectives, somewhat influenced by Annibale Carracci's altarpiece of the same subject.

While many came to work in the studio, Crespi established after Cignani's departure, few became notable. Antonio Gionima was moderately successful. Others included Giovanni Francesco Braccioli; Giacomo Pavia; Giovanni Morini; Pier Guariente; Felice and his brother Jacopo Giusti[5] and Cristoforo Terzi.[6] He may also have influenced Giovanni Domenico Ferretti. While the Venetian Giovanni Battista Piazzetta claimed to have studied under Crespi, the documentation for this is nonexistent.

Two of Crespi's sons, Antonio (1712–1781) and Luigi (1708–1779) became painters. According to their account, Crespi may have used a camera obscura to aid in depiction of outdoor scenes in his later years. After his wife's death, he became reclusive, rarely leaving the house except to go to daily mass.

Partial anthology of works

Woman with Lute

Woman with Lute-Pandurina.png) Woman with Pandurina

Woman with Pandurina Count Fulvio Grati

Count Fulvio Grati Cardinal Prospero Lambertini

Cardinal Prospero Lambertini Ecstasy of St Margaret of Cortona

Ecstasy of St Margaret of Cortona

- The Marriage at Cana, Art Institute of Chicago

- Holy Family (1688), Parish Church of Bergantino

- Madonna del Carmine

- Temptation of St. Anthony (1690), San Niccolò degli Albari, Bologna

- Aeneas, The Sibyl and Charon, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- Hecuba blinding Polynestor, Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels

- Tarquin and Lucretia, National Gallery, Washington D.C.

- The Triumph of Hercules, The Four Seasons, The Three Fates, Neptune and Diana, frescoes of Palazzo Pepoli Campogrande, Bologna

- The Finding of Moses & David and Abigail, Museo di Palazzo Venezia, Rome

- Love triumphant (L'Ingegno), Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg

- Chiron Teaches Achilles (1700s), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

- The Ecstasy of Saint Margaret of Cortona (1701), Duomo, Bologna

- Massacre of the Innocents (1706), Uffizi, Florence, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna, and National Gallery, Dublin

- The Fair at Poggio a Caiano (1709), Uffizi

- The Nurture of Jupiter (1729), Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth

- Singer at Spinet with an Admirer (1730s), Uffizi

- Village Fair with dentist (1715–20), Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan

- Series of The Seven Sacraments (1712), Gemäldegalerie, Dresden

- Meeting between James Stuart and the Prince Albani, Národní Galerie, Prague

- Annunciation with Saints (1722), Sarzana Cathedral

- The Crucifixion (Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan)

- Self-portrait (1725-1730), Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan

- The Assumption of the Virgin (1730), Archivio Arcivescovile, Lucca

- Two altarpieces for the church of the Gesù, Ferrara (1728–1729)

- Four altarpieces for the church of the Benedictine Monastery of San Paolo D'Argon, province of Bergamo (1728–1729)

- Martyrdom of Saint John the Evangelist

- Joshua Stopping the Sun (1737), Colleoni Chapel, Bergamo

- Martyrdom of Saint Peter of Arbuès (1737), Collegio di Spagna, Bologna

- Self-portrait, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna

- The Family of Zanobio Troni, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna

- The Lute Player, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- The Hunter, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna)

- The Messenger, Staatliche Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe

- Courtyard Scene, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna

- Searching for Fleas,(Louvre); variants (Uffizi), Museo Nazionale di San Matteo, Pisa, and Museo di Capodimonte, Naples

- The Woman Washing Dishes, Galleria degli Uffizi

- A Peasant Family with Boys Playing, London

- Peasants Playing Musical Instruments, London

- Peasants with Donkeys, London

- Importunate Lovers, Hermitage

- Peasant Flirtation, London

- Menghina from the Garden meets Cacasenno

- Music Library Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna

- Cupids at Play, El Paso Museum of Art

- St John Nepomuk Hears Confession from the Queen of Bohemia, Turin, Galleria Sabauda

- Man With Helmet, Nelson-Atkins Art Museum, Kansas City, Missouri

Notes

- Lanzi p. 162.

- "Artist Info". www.nga.gov. Retrieved 2017-08-18.

- Lanzi p. 162-3.

- "Giuseppe Maria Crespi | Italian painter". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-08-18.

-

- Guida di Pistoia per gli amanti delle belle arti con notizie, by Francesco Tolomei, 1821, page 177-178.

- Hobbes, 1849, p. 68

References

- Hobbes, James R. (1849). Picture collector's manual adapted to the professional man, and the amateur. T&W Boone; Digitized by Googlebooks. p. 68.

- Spike, John T. (1986). Giuseppe Maria Crespi and the Emergence of Genre Painting in Italy. Fort Worth: Kimball Museum of Art. pp. 14–35.

- Luigi, Lanzi (1847). Thomas Roscoe (ed.). The History of Painting in Italy; from period of the revival of the arts to the eighteenth century. Henry G. Bohn; Digitized by Googlebooks from Oxford University copy on January 31, 2007. pp. 162–165.

- Domenico Sedini, Giuseppe Maria Crespi, online catalogue Artgate by Fondazione Cariplo, 2010, CC BY-SA.

External links

![]()