Filippo Salvatore Gilii

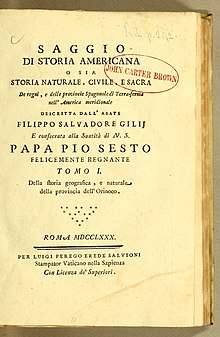

Filippo Salvatore Gilii (Spanish: Felipe Salvator Gilij) (1721–1789) was an Italian Jesuit priest who lived in the Province of Venezuela (in present day central Venezuela) on the Orinoco River. Gilii is a highly celebrated figure in early South American linguistics due to his advanced insights into the nature of languages. Gilii was born in Legogne, Italy (Umbria region). Most of what is known about the ethnology of the Tamanaco Indians was recorded by Gilii. One of his most notable works was Saggio di Storia Americana, o sia Storia Naturale, Civile, e Sacra De regni, e delle provincie Spagnuole di Terra-ferma nell' America meridionale, first published in four volumes in 1768.

Linguistic insights

Gilii recognized sound correspondences (e.g. between /s/ : /tʃ/ : /ʃ/ in the Cariban family) and predated William Jones' third discourse suggesting genealogical relationships between languages. Unlike Jones, Gilii presented evidence in support of his hypothesis.

He also discussed major concepts of linguistics such as areal features between unrelated languages, loanwords (among American languages and from American languages into European languages), word order, language death, language origins, and nursery forms of child language (i.e. Lallwörter) discussed by Roman Jakobson.

Gilii's nine lenguas matrices

Gilii found that the languages spoken in the Orinoco area belonged to nine "mother languages" (lenguas matrices), i.e. language families:

- Caribe (Cariban)

- Sáliva (Salivan)

- Maipure (Maipurean)

- Otomaca & Taparíta (Otomacoan)

- Guama & Quaquáro (Guamo)

- Guahiba (Guajiboan)

- Yaruro

- Guaraúno (Warao)

- Aruáco (Arhuacan)

This classification is one of the earliest proposals of South American language families.

See also

- Classification schemes for indigenous languages of the Americas

- Lorenzo Hervás y Panduro

External links

Bibliography

- Campbell, Lyle. (1997). American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509427-1.

- Del Rey Fajardo, José. (1971). Aportes jesuíticos a la filología colonial venezolana (Vols. 1-2). Caracas: Universidad Católica Andrés Bello, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, Seminario de Lenguas Indígenas.

- Denevan, William M. (1968). "Review of Ensayo de historia americana by Felipe Salvador Gilij & El Orinoco ilustrado y defendido by P. Jose Gumilla," The Hispanic American Historical Review, 48 (2), 288-290.

- Durbin, Marshall. (1977). "A survey of the Carib language family" In E. B. Basso (Ed.), Carib-speaking Indians: Culture, Society and Language (pp. 23–38). Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Gilij, Filippo S. (1780–1784). Sagio di storia americana; o sia, storia naturale, civile e sacra de regni, e delle provincie spagnuole di Terra-Ferma nell' America Meridionale descritto dall' abate F. S. Gilij (Vols. 1-4). Rome: Perigio. (Republished as Gilij 1965).

- Gilij, Filippo S. (1965). Ensayo de historia americana. Tovar, Antonio (Trans.). Fuentes para la historia colonial de Venezuela (Vols. 71-73). Caracas: Biblioteca de la Academia Nacional de la Historia.

- Gray, E.; & Fiering, N. (Eds.). (2000). The Language Encounter in the Americas, 1492-1800: A Collection of Essays. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Loukotka, Čestmír. (1968). Classification of South American Indian Languages. Los Angeles: Latin American Studies Center, University of California.