George William Gordon

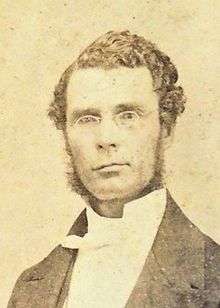

George William Gordon (1820 – 23 October 1865)[1] was a wealthy mixed-race Jamaican businessman, magistrate and politician, one of two representatives to the Assembly from St. Thomas-in-the-East Parish. He was a leading critic of the colonial government and the policies of Jamaican Governor Edward Eyre.[2]

George William Gordon | |

|---|---|

George William Gordon | |

| Born | 1820 Mavis Bank, Jamaica |

| Died | Executed,

23 October 1865 Morant Bay, Jamaica |

After the start of the Morant Bay rebellion in October 1865, Eyre declared martial law in that area, directed troops to suppress the rebellion, and ordered the arrest of Gordon in Kingston. He had him returned to Morant Bay to stand trial under martial law. Gordon was quickly convicted of conspiracy and executed, on suspicion of having planned the rebellion. Eyre's rapid execution of Gordon on flimsy charges during the crisis, and the death toll and violence of his suppression of the revolt, resulted in a huge controversy in Britain. Opponents of Eyre and his actions attempted to have him prosecuted for murder, but the case never went to trial. He was forced to resign. The British government passed legislation to make Jamaica a Crown Colony, governing it directly for decades. In 1969, the Jamaican government proclaimed Gordon as a National Hero of Jamaica [3].

Early life

George William Gordon was the second of eight children born in Jamaica to a Scottish planter, Joseph Gordon (1790?–1867),[4] and an enslaved woman, Ann Rattray (1792? – before 1865).[5] His siblings were Mary Ann (1813?), Margaret (1819?), Janet Isabella (1824?), John (1825?), Jane (1826?), Ann (1828?) and Ralph Gordon (1830). Gordon was self-educated, teaching himself to read, write, and perform simple accounting. At the age of ten, he was allowed to live with his godfather, James Daly of Black River, Jamaica. Within a year, Gordon began working in Daly's business.[6]

Business career

In 1836, young Gordon opened a store in Kingston and operated as a produce dealer. Richard Hill (Jamaica), a mixed-race lawyer and leader of the free coloured community, met him in that year and said of him, "He impressed me then, though young-looking, with the air of a man of ready business habits." In 1842, he had earned enough to be able to send his sisters to England and France to be educated. Three years later, worth £10,000, he married Lucy Shannon, the white daughter of an Irish newspaper editor.[7]

Gordon later moved to St. Thomas-in-the-East Parish at the eastern end of the island, where he became a wealthy businessman and a landowner.[6] In the 1840s, he married a white Jamaican woman named Mary Jane Perkins, and he co-founded the Jamaica Mutual Life Assurance Society, and was appointed a justice of the peace in seven parishes. In the early 1860s, Gordon lost heavily in coffee dealings.[8]

Political career

Gordon was elected from St. Thomas-in-the-East parish as a member of the House of Assembly. On more than one occasion, Gordon deputised as mayor of Kingston for Edward Jordon.[9] Gordon was a radical politician who was popular in the parish of St Thomas-in-the-East, and he was deeply affected by the suffering of the black poor. He complained to a previous governor, Charles Henry Darling, about the poor conditions of the Morant Bay gaol. In 1862, when he made similar complaints to Eyre, the governor immediately removed Gordon from the magistracy. The Colonial Office took the curious stance of backing Eyre while praising Gordon for calling for prison conditions to be improved.[10]

Gordon earned a reputation by the mid-1860s as a critic of the colonial government, especially Governor Edward John Eyre. He maintained a correspondence with English evangelical critics of colonial policy. He also established a Native Baptist church, where Paul Bogle was a deacon.[11]

In 1863, Gordon defeated his rival, a white planter, for a seat on the Assembly for St Thomas-in-the-East with the support of the small settler vote, galvanised by Bogle. Gordon was also made a member of the parish vestry. However, the colonial elite who ran the parish vestry objected to the presence of Gordon, because he represented the concerns of the black peasantry. A father and son team of the same name, Stephen Cooke, conspired to have Gordon expelled from the parish vestry, a move that angered the black peasantry. The next year, the settlers re-elected Gordon to the parish vestry, and he brought a court action against the custos of the parish, Baron von Ketelhodt.[12]

In May 1865 Gordon allegedly attempted to purchase an ex-Confederate schooner with a view to ferrying arms and ammunition to Jamaica from the United States of America, although this was unknown at the time.[13] In 1865 the mass of Jamaicans were ex-slaves and their descendants; they struggled with poverty and crop failure in the mostly rural economy, and the aftermath of crippling epidemics of cholera and smallpox.

Morant Bay Rebellion

There were several causes for the Morant Bay Rebellion of 1865, and one of them was outrage among the black peasantry of St Thomas-in-the-East over the colonial government's actions in expelling Gordon and Bogle from the local vestry.[14]

In October, a riot led by Bogle was ruthlessly suppressed by Eyre, with the support of Jamaican Maroons from Moore Town, and hundreds of black Jamaican men and women were killed by government forces without trial, or in hastily-arranged trials under martial law.[15]

Death and aftermath

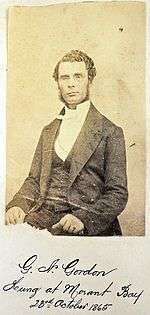

In October 1865, following the Morant Bay Rebellion led by Bogle, Governor Eyre ordered the arrest of Gordon, whom he suspected of planning the rebellion. By order of Eyre, Gordon was transported from Kingston, where martial law was not in force, to Morant Bay, where it was. Within two days Gordon was tried for high treason by court-martial, without due process of law, sentenced to death, and executed on 23 October.[16]

The execution of Gordon and the brutality of Eyre's suppression of the revolt, with hundreds of Jamaicans killed by soldiers and more executed after trials, made the affair a cause célèbre in Britain. John Stuart Mill and other liberals sought unsuccessfully to have Eyre (and others[17]) prosecuted. When they were unable to get the cases to trial, the liberals worked to bring civil proceedings against Eyre.[18] He was forced to resign from office but never went to trial.[19]

Legacy and honours

In the 20th-century aftermath of the labour rebellion of 1938, Gordon came to be seen as a precursor of Jamaican nationalism. The play George William Gordon (1938) by Roger Mais was about his life.

In 1960 the Parliament of Jamaica moved into the new Gordon House, named for the politician.[20]

In 1969, Gordon and Bogle were each proclaimed as Jamaican National Heroes in a government ceremony at Morant Bay.

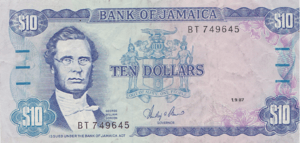

In 1969, Jamaica converted its currency to a decimal system, and it issued new currency. Gordon was featured on the ten-dollar note (now a coin).

George William Gordon is mentioned in the song "Innocent Blood" and also "See them a come" by the reggae band Culture. He is noted in the song "Silver Tongue Show" by Groundation, "Give Thanks and Praise" by Roy Rayon, "Prediction" and "Born Fe Rebel" by Steel Pulse, and "Our Jamaican National Heroes" by Horace Andy.

References

- "George William Gordon", Jamaica Information Service.

- "George William Gordon (Biographical details)". The British Museum. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- "George William Gordon". Jamaica Information Service. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "National Heroes | The National Library of Jamaica". Nlj.gov.jm. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- George William Gordon Website Archived 26 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "National Heroes". Jis.gov.jm. Archived from the original on 7 September 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- C.V. Black, A History of Jamaica (London: Collins, 1975), p. 188.

- Gad Heuman, The Killing Time: The Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1994), p. 63.

- C.V. Black, A History of Jamaica (London: Collins, 1975), p. 189.

- Heuman, The Killing Time, pp. 10, 64–5.

- "Jamaica National Heritage Trust – Jamaica". Jnht.com. 19 February 2007. Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- Heuman, The Killing Time, pp. 66–7.

- Handford, Peter. "Edward John Eyre and the Conflict of Laws" (PDF). Melbourne University Law Review. [2008]: 822–860. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- Heuman, The Killing Time, pp. 14, 184.

- Gad Heuman, The Killing Time: The Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1994).

- Gad Heuman, The Killing Time: The Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1994), pp. 146–151.

- Specifically Colonel Abercrombie Nelson and Lieutenant Herbert Brand (Hanford, page 841).

- In relation to the civil proceedings, see Phillips v Eyre (1870) LR 6 QB 1

- Heuman, The Killing Time, pp. 164–182

- "History of Jamaica's Legislature". Japarliament.gov.jm. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

Further reading

Duncan Fletcher, Personal Recollections of the Honourable George W. Gordon, late of Jamaica (1867), available online