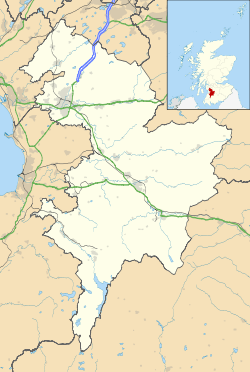

Gatehead, East Ayrshire

The village or hamlet of Gatehead is located in East Ayrshire, Parish of Kilmaurs, Scotland. It is one and a quarter miles from Crosshouse and one and a half miles from Kilmarnock. In the 18th and 19th centuries the locality was a busy coal mining district. The settlement runs down to the River Irvine where a ford and later a bridge was located.

Introduction

Gatehead, an old colliers' village,[1] lies at or near the junction of several roads, namely the main road to Kilmarnock, Dundonald & Troon , nearby are other roads that run to Symington or Kilmarnock via Old Rome and Earlston, another to Springside, North Ayrshire or Crosshouse via Craig and yet another to Crosshouse, branching off the main Kilmarnock road. The settlement no doubt developed to cater for travellers on these roads and from the railway which was used also by carts and pedestrians as a 'toll' road or tramway prior to 1846. The local shop and post office next to the old station closed within the last ten years (1985 OS). The River Irvine forms the boundary with South Ayrshire, previously 'Kyle and Carrick', Parish of Dundonald.

History

Gatehead is most likely to have been named after the Turnpike road and the toll bar or gate. A 'Gatehead Toll Bar' is still marked nearby on the road to Laigh Milton mill and the Craig House estate as late as 1860 on the Ordnance Survey (OS) map of that year. 'Gatehead' is apparently first recorded marked on General Roy's Military Survey map of Scotland (1745–55) and then by Armstrong's 1775 map.[2] The RCAHMS website records the site of a Toll house at NS 3898 3670.[3] Archibald Adamson records a walk through Old Rome and Gatehead in 1875.[4] He mentions a neat lodge house at Fairlie, then owned by a Captain Tait and records that the Irvine bridge has recently replaced an older one. The Old Rome miners cottages are in ruins following the local coal pits being worked out and the distillery ruins are still apparent. He goes on to say that Gatehead was established around fifty years back, i.e. circa 1825, and has neither kirk, smithy, mill or market, but it does have a station.

Laigh Milton viaduct over the River Irvine stands nearby. This is the oldest railway viaduct in Scotland,[5] and one of the oldest in the world.[6]

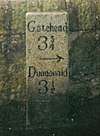

The Cochrane Inn is likely to have originally been a coaching inn, serving the stagecoach route from Kilmarnock to Troon and Ayr. A milestone near the Crosshouse junction on the main road in 1860 gave Troon as 7 miles and Dundonald as 21⁄4 miles and another near the junction for Laigh Milton Mill gave Ayr as 10 miles and Kilmarnock as 21⁄4 miles.

A hamlet called 'Milton' is marked on the 1821 and 1828 maps,[7][8] but the name is not marked on the 1860 and the more recent OS maps. Laigh Milton mill still stands, but is now in a ruinous condition (2007). A laithe or saw mill existed across the river from Craig House, which had its own mill and a ford, together with another mill near Drybridge at 'Girtrig' or previously 'Greatrig'.

A 'Romford', 'Rameford', 'Room' or 'Rome Ford' was situated where the modern road bridge crossing the River Irvine is located. In Scots 'Rommle' is to rumble or stir violently,[9] a more likely explanation than some memory of the Roman occupation of Scotland. Another suggestion is that 'Room' or 'Rome' in Scots meant a small farm.[9][10] Both Thomson[8] and Ainslie[7] show the railway apparently branching and crossing the Irvine by means of a bridge near to the ford and this branch or mineral line halting near Fairlie House on Thomson's map and carrying on towards Symington on Ainslie's map. This branch may never have been built, shown due to its planned, but not executed, construction.

The railway level crossing has been here[7] since the Kilmarnock and Troon Railway opened in 1811,[11] but as stated, the name 'Gatehead' predates the railway. A stable was located hereabouts and the horses pulling the wagons were changed here.[12] Gatehead railway station closed in 1967, having opened with the rest of the line on 6 July 1812. The 1860 OS map shows a milepost indicating Kilmarnock at 23⁄4 miles and Troon at 71⁄4 miles.

A distillery once existed near Old Rome,[4] although no signs of its existence are now visible. A smithy existed, as marked on the 1880s OS. It was on the left-hand side, just across the bridge from Old Rome. A school existed at Old Rome that may also have been used by pupils from Gatehead.

Estates

Gatehead was surrounded by several country estates which provided employment and helped create the need for the establishment of settlements such as Old Rome and Gatehead.

The Craig estate of the Dunlops and more recently the Pollok-Morrises, lying within the ancient Barony of Robertoun, lay just beyond Laigh Milton Mill and the Fairlie estate is just across the River Irvine. Capringtoun, a Cunninghame clan estate is nearby and Thorntoun and Carmel Bank (previously known as Mote or Moit in 1604),[13] previously another Cunninghame property lies near Springside.

Craig House was sold after WWII to Glasgow Corporation as a 'respite home' for mainly Glaswegian children .,[14] After the school closed it was badly vandalised and eventually burnt out becoming a ruin. It has since been rebuilt and converted into flats with executive style houses built in the grounds extending right up to the mansion.

Fairlie was locally termed "Fairlie o' the five lums" according to Adamson in 1875,[15] on account of the five large chimneys in a row along the roof ridge of the mansion.[16] Fairlie had been known as 'Little Dreghorn', until William Fairlie of Bruntsfield gave it his family name in around 1704.[17] Robert Gordon's manuscript map of ca. 1636 – 52 indicates a small mansion at 'Little Drogarn',[18] and it has been suggested by McNaught that the woodland here was locally known as 'Old Rome Forest' at this time.[19] The 'Laird of Fairlie' also owned Arrothill. Sir William Cunninghame of Fairlie and Robertland is recorded by George Robertson in 1823 as living "in a shewy modern mansion",[20] i.e. Fairlie. A mineral spring known as 'Spiers Well' existed near Gatehead in 1789.[21]

At the time of Alexander Fairlie one of his estate workers, Josey Smith,[22] composed the following lines :-

|

The Barony of Robertoun

This barony, once part of the Barony of Kilmaurs, ran from Kilmaurs south to the river Irvine. It had no manor house and belonged to the Eglinton family latterly. The following properties were part of the barony: Gatehead, parts of Kilmaurs, Craig, Woodhills, Greenhill, Altonhill, Plann, Hayside, Thorntoun, Rash-hill Park, Milton, Windyedge, Fardelhill, Muirfields, Corsehouse and Knockentiber and Busbie.[21]

Robert Burns

Robert Burns' father worked on the Fairlie Estate as a gardener for a time.[23] Old Rome Forest or Old Room Ford was a house in the Fairlie estate where Jean Brown, an aunt of Burns on his mother's side, lived with her husband, James Allan. When Burns had to go into hiding as a result of James Armour's warrant for his arrest, the poet stayed at his aunt's house. Nothing remains of Old Rome Forest, but according to Duncan M'Naught, (in an article in the Burns Chronicle, 1893) the house was on the Fairlie estate.[24] McNaught states that Fairlie House was called 'Old Rome Forest' in his day.

Collieries and Coal Pits

A branch of rail way (sic) ran in from the Kilmarnock and Troon 'main line' near Gateside to coal works belonging to Sir William Cuninghame of Robertland Bart. The length of the branch was four furlongs and one hundred and seven yards nearly. The line crossed the river downstream of the Romeford bridge.[25]

On the 1923 OS mineral lines still run to collieries near Earlston, Nether Craig and Cockhill farm (Fairlie (Pit No.3)). Earlston has a sawmill marked as well. The 1860 OS names the 'Fairlie Branch' and indicates its operation by the Glasgow and South Western Railway company. The bridges built for these lines are still clearly visible with the exception of the wooden bridge crossing the river near the original stone viaduct. The latter either being demolished or succumbing to the elements when the main line was moved to its current position. The 1895 OS shows a colliery at Templeton near Earlston and another mineral line running up to a colliery at Bogside near Ellerslie in Kilmarnock. A coal pit is marked at Old Rome in 1860, with miners rows and a school. The school building survives as a private house, being the last building (2007) on the left before the junction for Symington. Another coalpit was located near a smithy opposite Peatland House. John Finnie of 'Kilmarnock fame' enlarged Peatland House for his sisters.

Farms

West and East Gatehead Farms are close by, New Bogside is on the direct Crosshouse road, while Arrathill (1860 OS) or Arrothill (1985 OS) farm lies across the river towards Earlston. An Arrathill Mount overlooks Old Rome . In 1829 the Kilmarnock & Troon Railway agreed to pay compensation to the Earl of Eglinton of £185.13s.10d for damage to East & West Gatehead Farms and land used.[26]

Cholera

In 1832 an outbreak of Cholera claimed many lives in Kilmaurs and to prevent the entrance of strangers or vagrants, guards were placed at Gatehead, Knockentiber and other places to prevent any communication between the occupants of Kilmaurs and the rest of the community.[27]

Scrappy

There was a scrap metal yard in the village which was located on the main road just south of the existing railway . This site could have possibly been sidings of the rail network and railway station which was on the north side of the railway . The site, which was surrounded by a mesh fence on the south village side and a sandstone wall on the main road and railway sides had a large Sandstone building was located within it . When the Yard was closed the land was used to build houses on .

Views in and around Gatehead – 2007

- Gatehead station which opened in 1812 and closed on 3 March 1969.

- A coal train from the 'Troon' end of the line.

- A coal train heading up to Kilmarnock.

- Looking towards the River Irvine, Old Rome and the Fairlie estate.

- Looking towards the Cochrane Inn from the level crossing, the old post office and shop on the left.

- West Gatehead farm. 2007. A track ran from here to Fairlie Pit No.3 across the Laigh Milton viaduct.

- Laigh Milton viaduct, looking towards the old waste bings of Fairlie Colliery (Pit No.3).

- Craig House from Laigh Milton viaduct.

- Laigh Milton Mill.

- The lodge house and gates at Fairlie House.

- The woodland policies and Fairlieholm from Gatehead.

- Old Rome from Gatehead's bridge over the Irvine.

- The old railway bridge at Templeton on the G&SWR.s Fairlie branch.

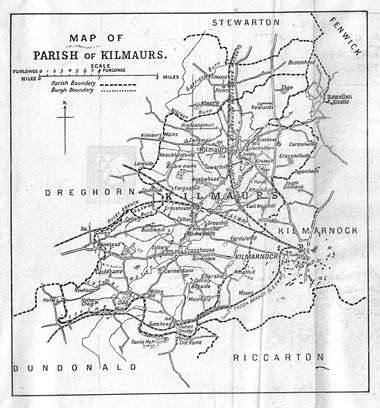

A Map of the Parish of Kilmaurs

See also

- Agnes Broun

- Earlston, East Ayrshire

- Old Rome, South Ayrshire

- Allan Line Royal Mail Steamers

- Murder of James Young - the act took place near Fortacres Farm.

References

- Groome, Francis H. (1903). Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland. Pub. Caxton. London. P. 643.

- Armstrong and Son. Engraved by S.Pyle (1775). A New Map of Ayr Shire comprehending Kyle, Cunningham and Carrick.

- RCAHMS Canmore

- Adamson, Archibald R. (1875). Rambles Round Kilmarnock. Pub. Kilmarnock. Pps. 93 – 94.

- "The Official Site of Scotland's National Tourist Board". Archived from the original on 3 May 2007. Retrieved 21 March 2007.

- "The Official Site of Scotland's National Tourist Board". Archived from the original on 29 August 2008. Retrieved 21 March 2007.

- Ainslie, John (1821). A Map of the Southern Part of Scotland.

- Thomson, John (1828). A Map of the Northern Part of Ayrshire.

- Warrack, Alexander (1982)."Chambers Scots Dictionary". Chambers. ISBN 0-550-11801-2.

- 'Room' or 'Rome' Archived 12 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Awdry, Christopher, (1990). Encyclopaedia of British Railway Companies. London: Guild Publishing.

- Mackintosh, Ian M. (1969), Old Troon and District. Pub. George Outram, Kilmarnock. P. 43.

- Pont, Timothy (1604). Cuninghamia. Pub. Blaeu in 1654.

- Strawhorn, John and Boyd, William (1951). The Third Statistical Account of Scotland. Ayrshire. Pub. P. 475

- Adamson, Archibald R. (1875). Rambles Round Kilmarnock. Pub. Kilmarnock. P.93.

- Millar, A. H. (1885).Which in more recent times was shortened to "Fairlie Five Lums" by local people . The Castles & Mansions of Ayrshire. Reprinted The Grimsay Press. ISBN 1-84530-019-X. P. 78

- Paterson, James (1863–66). History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. V.II. – Part II – Kyle. J. Stillie. Edinburgh. P. 477.

- Gordon, Robert (1636–52). Cuningham. Manuscript map held by the NLS.

-

- McNaught, Duncan (1912). Kilmaurs Parish and Burgh. Pub. A.Gardner.

- Robertson, George (1823). A Genealogical Account of the Principal Families in Ayrshire. Pub. A.Constable, Irvine. P. 330

- National Archives of Scotland. RHP3 / 37.

- Strawhorn, John (1995). The Scotland of Robert Burns. Darvel : Alloway Publishing. ISBN 0-907526-67-5. P. 56.

- Private Burns

- Old Rome Forest

- Mackintosh, Ian M. (1969), Old Troon and District. Pub. George Outram, Kilmarnock. Map facing p. 48.

- National Archives of Scotland. GD3/3/150.

-

- McNaught, Duncan (1912). Kilmaurs Parish and Burgh. Pub. A.Gardner. P. 254.