Laigh Milton Viaduct

Laigh Milton Viaduct is a railway viaduct near Laigh Milton mill to the west of Gatehead in East Ayrshire, Scotland, about 5 miles (8 km) west of Kilmarnock. It is probably the world's earliest surviving railway viaduct on a public railway,[1] and the earliest known survivor of a type of multi-span railway structure subsequently adopted universally.[2]

Laigh Milton Viaduct | |

|---|---|

Laigh Milton Viaduct in East Ayrshire over the River Irvine | |

| Coordinates | 55.59882°N 4.56719°W |

| Carries | Traffic suspended |

| Crosses | River Irvine |

| Locale | Laigh Milton mill at Gatehead in East Ayrshire, Scotland |

| Official name | Laigh Milton Viaduct |

| Maintained by | East Ayrshire Council |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | William Jessop |

| Total length | 270 ft (82.3 m) long by 19 ft (5.8 m) wide. |

| Longest span | 40 ft (12.2 m) span with piers 9 ft (2.7 m) wide. |

| History | |

| Opened | 1812 |

| |

The viaduct was restored in 1995-96[3] and is a Category A listed structure since 1982.[4] It bridges the River Irvine which forms the boundary between East Ayrshire and South Ayrshire.

It was built for the Kilmarnock and Troon Railway, opened in 1812; the line was a horse drawn plateway (although locomotive traction was tried later). The first viaduct was closed in 1846 when the railway line was realigned to ease the sharp curve for locomotive operation, and a wooden bridge was built a little to the south to carry the realigned route. This was in turn replaced by a third structure further south again, which carries trains at the present day.

The first Laigh Milton viaduct

The first viaduct was constructed as part of the Kilmarnock and Troon Railway, which opened on 6 July 1812. It is located at National Grid Reference NS 3834 3690.

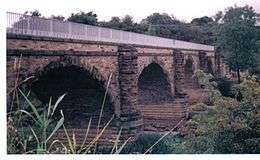

It was built with four segmental arches of 12.3 m (40 feet) span, and a rise of one-third span; the voussoirs were 610 mm (24 inches) thick. The railway was carried about 8 m (25 feet) above the river surface.[2]

The arches were of local freestone with sandstone ashlar facings and rounded cutwaters: these were later extended to form semi-circular buttresses. Built in 1811 - 1812, it is the oldest surviving railway viaduct in Scotland.[1] and one of the oldest in the world.

It is about 82 m (270 ft) long by 5.8 m (19 ft) wide over all. The piers are 9 ft (2.7 m) wide. Photographs taken prior to the recent restoration show the viaduct without parapets, and there is no evidence that these were provided.[5]

The engineer for the whole line was William Jessop, and the resident engineer was Thomas Hollis, and he was probably allowed considerable autonomy by Jessop. The stonemason was probably John Simpson, who had been extensively employed by Jessop at Ardrossan and on the Caledonian Canal.[2]

Hollis was refused permission to dismantle part of the mill dam to lower water level for pier construction, and "in July 1809 he was authorized to proceed by means of a cofferdam, involving 'very little more expense', with the advantage that 'the stones for the bridge can be floated down on a punt'."[6]

Paxton suggests that the original standard of construction was poor:

This utilitarian, medium-scale viaduct was designed in accordance with traditional rather than 1810 state-of-the-art practice. It did not incorporate the hollow cross-tied spandrel improvement then being adopted with increasing frequency by leading engineers. If this had been adopted here instead of clay fill, it would have obviated the spandrel bulging and some of the stone loss that occurred. Much of the viaduct's stone quality and some workmanship at the west end were only just adequate for the purpose ... but the flat-stone, lime-mortar-bedded, pier hearting carried up to 1.5 m above arch springing was an effective feature which had probably saved the piers from collapse. In cross-section, the spandrels presented an unusual application of the classic gravity retaining wall.[2]

In the later decades of the twentieth century the viaduct had fallen into an ever-worsening condition, with much serious erosion and loss of facings; the western arch had sagged and the second arch had hogged; cracks up to 60 mm had opened up in the extrados of the arch rings. It had become obvious that the structure was near to collapse, and in February 1992 the Laigh Milton Viaduct Conservation Project was formed.[2] It is described below.

When it was by-passed, it remained in place, and was used as a footway and possibly for cartage to and from the pit on the west side of the river, Fairlie Colliery No. 3.

Second viaduct

In 1846 the proprietors determined the need to improve their railway for ordinary locomotive use. Part of this process involved easing some of the very sharp curves on the line. This process included providing a new viaduct to cross the River Irvine, a little distance south of the first viaduct. This second bridge was wooden; it was located where the river banks were lower than at the first viaduct, and elevated approaches were needed. Little detail of this second viaduct has survived.

This structure is no longer in place, but the remains of the abutments can still be seen in the River Irvine when the water is exceptionally low.

Third viaduct

In 1865 the wooden structure was itself replaced by a new viaduct further south, improving the alignment of the railway once more. The new viaduct remains in use by Network Rail at the present day; it may be known as Gatehead Viaduct.

The Kilmarnock & Troon Railway

In 1807 the Marquess of Titchfield (later the 4th Duke of Portland) commissioned William Jessop to build a railway line between Kilmarnock and Troon. Bentinck had coal pits near Kilmarnock and was constructing a harbour at Troon. Much of his coal was destined for Ireland from Troon.

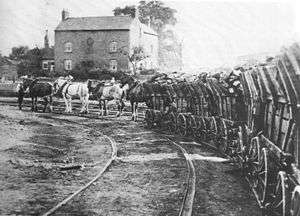

The line opened in 1812; it was made as a double track line, as a plateway, in which the rails were L-shaped in cross section; wagons with plain wheels could use the line. The railway used horses for traction; a locomotive was tried, but it was too heavy and broke the plates. Passengers were carried by independent hauliers.

The plateway system had significant limitations, and the Company converted the line to an edge railway from 1841. Locomotive traction was intended, and some very sharp curves on the original line needed to be eased. Laigh Milton Viaduct was located on a sharp curve, and the conversion work included the provision of a new structure a short distance to the south.

The Kilmarnock and Troon Railway was a local line, and as larger concerns extended their area of influence, the Glasgow, Paisley, Kilmarnock and Ayr Railway (GPK&AR) leased the line from 1846, and built connecting lines so that it became an integral part of their network. The alignment at the second Laigh Milton Viaduct was still unsatisfactory and in 1865 a third viaduct was built further south. The GPK&AR was taken over by the Glasgow and South Western Railway and the line remains in use today (2013), owned by Network Rail. Passenger and freight trains operate over the route.[7][8][9]

Conservation project

In February 1992 the Laigh Milton Viaduct Conservation Project was formed, with the objective of conserving the structure. The Project did not necessarily anticipate taking on ownership, but this became necessary as a condition of funding, and Strathclyde Regional Council agreed to let and oversee the main contract for restoration, and to take over ownership on completion.

Ownership proved difficult to trace, but was eventually found to rest with adjoining farm owners, and the viaduct was purchased from them for a nominal sum.

Contracts were prepared on a design and build basis, and funding was obtained from:

- National Heritage Memorial Fund: £400,000

- Historic Scotland: £277,300

- European Union: £200,000

- Strathclyde Regional Council: £63,000, in addition to roads and planning services

- Kyle & Carrick District Council: £65,000

- Kilmarnock & Loudoun District Council: £45,000

- Enterprise Ayrshire: £15,000

The lowest tender for execution of the project was accepted in February 1995, and the out-turn was £1.024 million, representing 95% of the funding; preliminary works accounted for 1.5% and legal costs and administration for 3.5%.[2] Barr Construction were the main contractor.

Paxton records that

The viaduct had become fragile largely because of crumbling of much of its stone, which was not of the best quality, being of a minutely fissured weak texture. With lack of maintenance, vegetation and weather effects this weakness had led to widespread stone loss and serious undercutting to all piers at or near water level. The west pier was seriously cracked, mainly around its traditional hearting, and had lost about a third of its 2.9 m thickness. Some movement had occurred long ago causing stretching and hogging of the arches adjoining the west pier. ... The north spandrel wall had suffered extensive stone loss at the top and some peeling away of pier bull-noses.[2]

The site agent had shown initiative by artificially ageing a trial area of new stone with peat and milk, but it was insisted that the new stone should remain untreated in order that old and new work could be identified.

The original viaduct had not had parapets and had probably never had handrails, which were now essential for safety. It was considered appropriate to make them of steel in an authentic period style, and after examining photographs of the cast iron railings of Chirk Aqueduct and other early examples, masonry copings and light-coloured railings were provided. The preservation of the 300 mm distortion of arch 2 was maintained; the light coloured railings are unobtrusive visually against the sky.

The viaduct was formally re-opened on 29 October 1996, and ownership of the viaduct was handed over to East and South Ayrshire Councils on 18 April 1997.[2]

Indications from Ordnance Survey and other maps

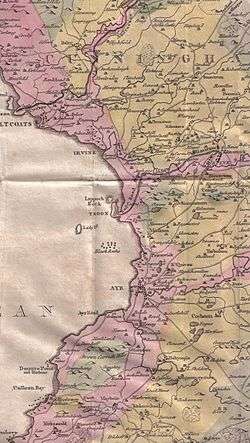

John Ainslie's map of 1821 and John Thomson's map of 1828 both show the route of the Kilmarnock & Troon railway and the position of Laigh Milton viaduct crossing the River Irvine.[10][11]

The first Ordnance Survey map of 1860 shows a farm track crossing the viaduct as part of a byway from West Gatehead farm to Cockhill farm and the Craig estate. The new wooden viaduct of 1846 carries the railway. The new bridge required embankments to give sufficient height over the river, whereas the first viaduct was sprung from higher river embankments. On the Troon side the site of the old track has been obliterated by Fairlie Colliery (Pit No.3) and its spoil heaps.

| Etymology |

| 'Laigh' is the Scots for 'Low'. A 'Toun' or 'Ton' was a farm and its outbuildings, associated here with the Mill as millers often farmed on a small scale.[12] |

The 1898–1904 Ordnance Survey map shows that the wooden bridge (the second structure) has been abandoned and a new bridge built further up river.

The 1911 Ordnance Survey map marks the trackbed alignment of the first and second bridges, whilst the 1860 mineral line to Thorntoun and Gatehead collieries is now shown as a footpath. Fairlie Colliery (Pit No.3) is still active with several sidings and spoil heaps. No track or lane is shown running to West Gatehead farm.

McNaught's map of 1912 shows the colliery siding and indicates the access over the old viaduct to West Gatehead.[13] It is likely that this access across Laigh Milton viaduct to the colliery allowed coal to be taken off the site by road and allowed pedestrian access to the colliery.

The 1921–28 Ordnance Survey map shows the area as Laigh Milton for the first time. The first viaduct is still clearly shown as part of the farm track to Cockhill farm from West Gatehead. No sign of the wooden viaduct is indicated and a saw mill is now marked, possibly the cause of the need for the extra definition of the name of the site.

The 1985 1:25,000 Ordnance Survey map shows the inter-farm route as still intact; the saw mill is not marked; and Laigh Milton mill had become a public house. The embankments of the old railway line that ran up to the old wooden viaduct are however shown here.

Traditions and local history

The viaduct has gone by several alternative names, such as Gateside Viaduct, Drybridge Viaduct, West Gatehead Viaduct or even the 'wet bridge',[14] as distinct from the nearby 'Drybridge'. [15]

Gatehead railway station was situated nearby, in the village of that name. It closed on 3 March 1969. Gatehead is likely to be named from the turnpike road and the tool bar. A 'Gatehead Toll Bar' is still marked on the road down to Laigh Milton mill and the Craig house estate on the 1860 OS map.

A hamlet called 'Milton' is marked on the 1821 and 1828 maps,[10][11] but the name is not marked on the 1860 and the more recent OS maps.

The remains of the old Drybridge railway station and the village of the same name are nearby. The name 'Drybridge' comes from the fact that most bridges up until the era of the railways were built over watercourses and were therefore 'wet bridges'. A 'Dry bridge' was such a novelty that the name has survived ever since. This part of the railway is still active as the part of the Glasgow South Western Line (and officially known as the 'Burns Line') running from Kilmarnock to Troon.

Views of Laigh Milton Viaduct in 2007

- Looking towards the old bings of Fairlie Colliery (Pit No.3)

- A side view, looking across to the 'Troon' side

- Detail of a supporting pier, buttress, ashlar construction, etc.

- A freight train can be seen on the 'new bridge' through the arch.

- The 'new' railway bridge can be seen through the arch on the left

- The river Irvine and the view of the viaduct from near Laigh Milton Mill

- The operational bridge from the restored viaduct

- The Gatehead side embankment of the 1846 to 1865 wooden bridge

The foundations of the wooden bridge in the river, 2008 - A section of the replica plateway; this is not an accurate reproduction

- Detail of a section of the replica of the Kilmarnock and Troon plateway

- An original plateway sleeper situated below the bridge with several others

- The restored viaduct trackbed

- The old Fairlie Colliery's (Pit No.3) bings on the 'Troon' side of the river

- Laigh Milton Mill

Another early Scottish railway structure

The Blackhall Bridge in Paisley was built in the period 1808 - 1810 as an aqueduct for the Glasgow, Paisley and Ardrossan Canal. It was converted for railway use in 1885, and currently carries the Paisley Canal branch railway. The bridge is probably the longest span masonry aqueduct of the canal age on a British canal, and one of the world's earliest bridges carrying a public railway.[1]

References

- Roland Paxton and Jim Shipway, Civil Engineering Heritage: Scotland Lowlands and Borders, Thomas Telford Publishing, London, 2007, ISBN 978-0-7277-3487-7.

- R A Paxton, Conservation of Laigh Milton Viaduct, Ayrshire, Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers, Volume 126, London, 1998

- Sou' West the G&SWR Newsletter, P.5

- Engineering Timelines, at

- Laigh Milton Mill, Railway Viaduct, on the website of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland, at

- Kilmarnock and Troon Minute Book, quoted in Paxton (ICE)

- Henry Grote Lewin, Early British Railways: A short history of their origin & development: 1801-1844, The Locomotive Publishing Co Ltd, London, 1925

- Ian M Mackintosh, Old Troon and District George Outram, Kilmarnock, 1969

- William Robertson, Old Ayrshire Days, Stephen & Pollock, Ayr, 1905

- Ainslie, John (1821). A Map of the Southern Part of Scotland.

- Thomson, John (1828). A Map of the Northern Part of Ayrshire.

- Warrack, Alexander (1982)."Chambers Scots Dictionary". Chambers. ISBN 0-550-11801-2.

- McNaught, Duncan (1912). Kilmaurs Parish and Burgh. Pub. A.Gardner.

- Adamson, Archibald R. (1875). Rambles Round Kilmarnock. Pub. T.Stevenson, Pps. 168–170.

- http://helch.net/