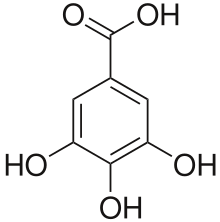

Gallic acid

Gallic acid (also known as 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoic acid) is a trihydroxybenzoic acid, a type of phenolic acid, found in gallnuts, sumac, witch hazel, tea leaves, oak bark, and other plants. The chemical formula of gallic acid is C6H2(OH)3COOH. It is found both free and as part of hydrolyzable tannins. The gallic acid groups are usually bonded to form dimers such as ellagic acid. Hydrolyzable tannins break down on hydrolysis to give gallic acid and glucose or ellagic acid and glucose, known as gallotannins and ellagitannins, respectively.[1]

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

3,4,5-Trihydroxybenzoic acid | |||

| Other names

Gallic acid | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.228 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID |

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C7H6O5 | |||

| Molar mass | 170.12 g/mol | ||

| Appearance | White, yellowish-white, or pale fawn-colored crystals. | ||

| Density | 1.694 g/cm3 (anhydrous) | ||

| Melting point | 260 °C (500 °F; 533 K) | ||

| 1.19 g/100 mL, 20°C (anhydrous) 1.5 g/100 mL, 20 °C (monohydrate) | |||

| Solubility | soluble in alcohol, ether, glycerol, acetone negligible in benzene, chloroform, petroleum ether | ||

| log P | 0.70 | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | COOH: 4.5, OH: 10. | ||

| -90.0·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

| Hazards | |||

| Main hazards | Irritant | ||

| Safety data sheet | External MSDS | ||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose) |

5000 mg/kg (rabbit, oral) | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related |

phenols, carboxylic acids | ||

Related compounds |

Benzoic acid, Phenol, Pyrogallol | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Gallic acid forms intermolecular esters (depsides) such as digallic and trigallic acids, and cyclic ether-esters (depsidones).[2]

Gallic acid is commonly used in the pharmaceutical industry[3] as a standard for determining the phenol content of various analytes by the Folin-Ciocalteau assay; results are reported in gallic acid equivalents.[4] Gallic acid can also be used as a starting material in the synthesis of the psychedelic alkaloid mescaline.[5]

The name is derived from oak galls, which were historically used to prepare tannic acid. Despite the name, gallic acid does not contain gallium. Salts and esters of gallic acid are termed "gallates".

Historical context and uses

Gallic acid is an important component of iron gall ink, the standard European writing and drawing ink from the 12th to 19th centuries, with a history extending to the Roman empire and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD) describes the use of gallic acid as a means of detecting an adulteration of verdigris[6] and writes that it was used to produce dyes. Galls (also known as oak apples) from oak trees were crushed and mixed with water, producing tannic acid. It could then be mixed with green vitriol (ferrous sulfate) — obtained by allowing sulfate-saturated water from a spring or mine drainage to evaporate — and gum arabic from acacia trees; this combination of ingredients produced the ink.[7]

Gallic acid was one of the substances used by Angelo Mai (1782–1854), among other early investigators of palimpsests, to clear the top layer of text off and reveal hidden manuscripts underneath. Mai was the first to employ it, but did so "with a heavy hand", often rendering manuscripts too damaged for subsequent study by other researchers.[8]

Gallic acid was first studied by the Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele in 1786.[9] In 1818, French chemist and pharmacist Henri Braconnot (1780–1855) devised a simpler method of purifying gallic acid from galls;[10] gallic acid was also studied by the French chemist Théophile-Jules Pelouze (1807–1867),[11] among others.

Gallic acid is a component of some pyrotechnic whistle mixtures.

Metabolism

Biosynthesis

Gallic acid is formed from 3-dehydroshikimate by the action of the enzyme shikimate dehydrogenase to produce 3,5-didehydroshikimate. This latter compound tautomerizes to form the redox equivalent gallic acid, where the equilibrium lies essentially entirely toward gallic acid because of the coincidentally occurring aromatization.[12][13]

Degradation

Gallate dioxygenase is an enzyme found in Pseudomonas putida that catalyses the reaction

- gallate + O2 → (1E)-4-oxobut-1-ene-1,2,4-tricarboxylate.

Gallate decarboxylase is another enzyme in the degradation of gallic acid.

Conjugation

Gallate 1-beta-glucosyltransferase is an enzyme that uses UDP-glucose and gallate, whereas its two products are UDP and 1-galloyl-beta-D-glucose.

Research

It is a weak carbonic anhydrase inhibitor.[14] One study indicated that gallic acid has an effect on amyloid protein formation by modifying the properties of alpha-synuclein, a protein associated with the onset of neurodegenerative diseases.[15]

Gallic acid is assumed to be an antimutagen and is classified as a teratogen.[16][2]

Natural occurrence

Gallic acid is found in a number of land plants, such as the parasitic plant Cynomorium coccineum,[17] the aquatic plant Myriophyllum spicatum, and the blue-green alga Microcystis aeruginosa.[18] Gallic acid is also found in various oak species,[19] Caesalpinia mimosoides,[20] and in the stem bark of Boswellia dalzielii,[21] among others. Many foodstuffs contain various amounts of gallic acid, especially fruits (including strawberries, grapes, bananas),[22][23] as well as teas,[22][24] cloves,[25] and vinegars.[26] Carob fruit is a rich source of gallic acid (24-165 mg per 100 g).[27]

Production

Gallic acid is easily freed from gallotannins by acidic or alkaline hydrolysis. When gallic acid is heated with concentrated sulfuric acid, rufigallol is produced by condensation. Oxidation with arsenic acid, permanganate, persulfate, or iodine yields ellagic acid, as does reaction of methyl gallate with iron(III) chloride.[2]

Spectral data

| UV-Vis | |

|---|---|

| Lambda-max: | 220, 271 nm (ethanol) Spectrum of gallic acid |

| Extinction coefficient (log ε) | |

| IR | |

| Major absorption bands | ν : 3491, 3377, 1703, 1617, 1539, 1453, 1254 cm−1 (KBr) |

| NMR | |

| Proton NMR

|

δ : 7.15 (2H, s, H-3 and H-7) |

| Carbon-13 NMR

|

δ : 167.39 (C-1), |

| Other NMR data | |

| MS | |

| Masses of main fragments |

ESI-MS [M-H]- m/z : 169.0137 ms/ms (iontrap)@35 CE m/z product 125(100), 81(<1) |

Reference[20]

Esters

Also known as galloylated esters:

- Methyl gallate

- Ethyl gallate, a food additive with E number E313

- Propyl gallate, or propyl 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoate, an ester formed by the condensation of gallic acid and propanol

- Octyl gallate, the ester of octanol and gallic acid

- Dodecyl gallate, or lauryl gallate, the ester of dodecanol and gallic acid

- Epicatechin gallate, a flavan-3-ol, a type of flavonoid, present in green tea

- Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), also known as epigallocatechin 3-gallate, the ester of epigallocatechin and gallic acid, and a type of catechin

- Gallocatechin gallate (GCG), the ester of gallocatechin and gallic acid and a type of flavan-3ol

- Theaflavin-3-gallate, a theaflavin derivative

See also

- Hydrolyzable tannin

- Pyrogallol

- Syringol

- Syringaldehyde

- Syringic acid

- Shikimic acid

References

- Andrew Pengelly (2004), The Constituents of Medicinal Plants (2nd ed.), Allen & Unwin, pp. 29–30

- Edwin Ritzer; Rudolf Sundermann (2007), "Hydroxycarboxylic Acids, Aromatic", Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (7th ed.), Wiley, p. 6

- Fiuza, S. M.; Gomes, C.; Teixeira, L. J.; Girão da Cruz, M. T.; Cordeiro, M. N. D. S.; Milhazes, N.; Borges, F.; Marques, M. P. M. (2004). "Phenolic acid derivatives with potential anticancer properties—a structure-activity relationship study. Part 1: Methyl, propyl, and octyl esters of caffeic and gallic acids" (PDF). Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. Elsevier. 12 (13): 3581–3589. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2004.04.026. hdl:10316/45150. PMID 15186842.

- Andrew Waterhouse. "Folin-Ciocalteau Micro Method for Total Phenol in Wine". UC Davis. Archived from the original on 2008-03-27.

- Tsao, Makepeasce (July 1951). "A New Synthesis Of Mescaline". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 73 (11): 5495–5496. doi:10.1021/ja01155a562. ISSN 0002-7863.

- Pliny the Elder with John Bostock and H.T. Riley, trans., The Natural History of Pliny (London, England: Henry G. Bohn, 1857), vol. 6, p. 196. In Book 34, Chapter 26 of his Natural History, Pliny states that verdigris (a form of copper acetate (Cu(CH3COO)2·2Cu(OH)2), which was used to process leather, was sometimes adulterated with copperas (a form of iron(II) sulfate (FeSO4·7H2O)). He presented a simple test for determining the purity of verdigris. From p. 196: "The adulteration [of verdigris], however, which is most difficult to detect, is made with copperas; … The fraud may also be detected by using a leaf of papyrus, which has been steeped in an infusion of nut-galls; for it becomes black immediately upon the genuine verdigris being applied."

- Fruen, Lois. "Iron Gall Ink". Archived from the original on 2011-10-02.

- L.D. Reynolds and N.G. Wilson, "Scribes and Scholars" 3rd Ed. Oxford: 1991, pp 193–4.

- Carl Wilhelm Scheele (1786) "Om Sal essentiale Gallarum eller Gallåple-salt" (On the essential salt of galls or gall-salt), Kongliga Vetenskaps Academiens nya Handlingar (Proceedings of the Royal [Swedish] Academy of Science), 7: 30–34.

- Braconnot Henri (1818). "Observations sur la préparation et la purification de l'acide gallique, et sur l'existence d'un acide nouveau dans la noix de galle" [Observations on the preparation and purification of gallic acid, and on the existence of a new acid in galls]. Annales de Chimie et de Physique. 9: 181–184.

- J. Pelouze (1833) "Mémoire sur le tannin et les acides gallique, pyrogallique, ellagique et métagallique," Annales de chimie et de physique, 54: 337–365 [presented February 17, 1834].

- Gallic acid pathway on metacyc.org

- Dewick, PM; Haslam, E (1969). "Phenol biosynthesis in higher plants. Gallic acid". Biochemical Journal. 113 (3): 537–542. doi:10.1042/bj1130537. PMC 1184696. PMID 5807212.

- Satomi, H; Umemura, K; Ueno, A; Hatano, T; Okuda, T; Noro, T (1993). "Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors from the pericarps of Punica granatum L". Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 16 (8): 787–90. doi:10.1248/bpb.16.787. PMID 8220326.

- Liu, Y; Carver, J. A.; Calabrese, A. N.; Pukala, T. L. (2014). "Gallic acid interacts with α-synuclein to prevent the structural collapse necessary for its aggregation". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics. 1844 (9): 1481–1485. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2014.04.013. PMID 24769497.

- Hour, Tzyh-Chyuan; Liang, Yu-Chih; Chu, Iou-Sen; Lin, Jen-Kun (June 1999). "Inhibition of Eleven Mutagens by Various Tea Extracts, (−)Epigallocatechin-3-gallate, Gallic Acid and Caffeine". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 37 (6): 569–579. doi:10.1016/s0278-6915(99)00031-9.

- Zucca, Paolo; Rosa, Antonella; Tuberoso, Carlo; Piras, Alessandra; Rinaldi, Andrea; Sanjust, Enrico; Dessì, Maria; Rescigno, Antonio (11 January 2013). "Evaluation of Antioxidant Potential of "Maltese Mushroom" (Cynomorium coccineum) by Means of Multiple Chemical and Biological Assays". Nutrients. 5 (1): 149–161. doi:10.3390/nu5010149. PMC 3571642. PMID 23344249.

- Nakai, S (2000). "Myriophyllum spicatum-released allelopathic polyphenols inhibiting growth of blue-green algae Microcystis aeruginosa". Water Research. 34 (11): 3026–3032. doi:10.1016/S0043-1354(00)00039-7.

- Mämmelä, Pirjo; Savolainen, Heikki; Lindroos, Lasse; Kangas, Juhani; Vartiainen, Terttu (2000). "Analysis of oak tannins by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry". Journal of Chromatography A. 891 (1): 75–83. doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(00)00624-5. PMID 10999626.

- Chanwitheesuk, Anchana; Teerawutgulrag, Aphiwat; Kilburn, Jeremy D.; Rakariyatham, Nuansri (2007). "Antimicrobial gallic acid from Caesalpinia mimosoides Lamk". Food Chemistry. 100 (3): 1044–1048. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.11.008.

- Alemika, Taiwo E.; Onawunmi, Grace O.; Olugbade, Tiwalade A. (2007). "Antibacterial phenolics from Boswellia dalzielii". Nigerian Journal of Natural Products and Medicine. 10 (1): 108–10.

- Pandurangan AK, Mohebali N, Norhaizan ME, Looi CY (2015). "Gallic acid attenuates dextran sulfate sodium-induced experimental colitis in BALB/c mice". Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 9: 3923–34. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S86345. PMC 4524530. PMID 26251571.

- Koyama, K; Goto-Yamamoto, N; Hashizume, K (2007). "Influence of maceration temperature in red wine vinification on extraction of phenolics from berry skins and seeds of grape (Vitis vinifera)". Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 71 (4): 958–65. doi:10.1271/bbb.60628. PMID 17420579.

- Hodgson JM, Morton LW, Puddey IB, Beilin LJ, Croft KD (2000). "Gallic acid metabolites are markers of black tea intake in humans". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 48 (6): 2276–80. doi:10.1021/jf000089s. PMID 10888536.

- Pathak, S. B.; Niranjan, K.; Padh, H.; Rajani, M.; et al. (2004). "TLC Densitometric Method for the Quantification of Eugenol and Gallic Acid in Clove". Chromatographia. 60 (3–4): 241–244. doi:10.1365/s10337-004-0373-y.

- Gálvez, Miguel Carrero; Barroso, Carmelo García; Pérez-Bustamante, Juan Antonio (1994). "Analysis of polyphenolic compounds of different vinegar samples". Zeitschrift für Lebensmittel-Untersuchung und -Forschung. 199: 29–31. doi:10.1007/BF01192948.

- Goulas, Vlasios; Stylos, Evgenios; Chatziathanasiadou, Maria; Mavromoustakos, Thomas; Tzakos, Andreas (10 November 2016). "Functional Components of Carob Fruit: Linking the Chemical and Biological Space". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 17 (11): 1875. doi:10.3390/ijms17111875. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 5133875. PMID 27834921.