Frogner Park

Frogner Park (Norwegian: Frognerparken) is a public park located in the West End borough of Frogner in Oslo, Norway.[1] The park is historically part of Frogner Manor, and the manor house is located in the south of the park, and houses Oslo Museum. Both the park, the entire borough of Frogner as well as Frognerseteren derive their names from Frogner Manor.

| Frogner Park | |

|---|---|

Part of Frogner Park (from the Vigeland monolith) | |

| Location | Frogner Manor, Frogner, Oslo |

| Nearest city | Oslo |

| Area | 0.45 square kilometres (110 acres) |

| Established | C. 1750 as a baroque garden of Frogner Manor Early 20th century as a large public park |

Frogner Park contains, in its present centre, the Vigeland installation (Norwegian: Vigelandsanlegget; originally called the Tørtberg installation), a permanent sculpture installation created by Gustav Vigeland between 1924 and 1943.[2] It consists of sculptures as well as larger structures such as bridges and fountains. The installation is not a separate park, but the name of the sculptures within the larger Frogner Park. Informally the Vigeland installation is sometimes called "Vigeland Park" or "Vigeland Sculpture Park"; the director of Oslo Museum Lars Roede said "Vigeland Park" "doesn't really exist" and is "the name of the tourists," as opposed to "Oslo natives' more down-to-earth name, Frogner Park."[3]

The park of Frogner Manor was historically smaller and centered on the manor house, and was landscaped as a baroque park in the 18th century by its owner, the later general Hans Jacob Scheel. It was landscaped as a romantic park in the 19th century by then-owner, industrialist Benjamin Wegner. Large parts of the estate were sold to give room for city expansion in the 19th century, and the remaining estate was bought by Christiania municipality in 1896 and made into a public park. It was the site of the 1914 Jubilee Exhibition, and Vigeland's sculpture arrangement was constructed from the 1920s. In addition to the sculpture park, the manor house and a nearby pavilion, the park also contains Frognerbadet (the Frogner Baths) and Frogner Stadium. The Frogner Pond is found in the centre of the park.

Frogner Park is the largest park in the city and covers 45 hectares;[4] the sculpture installation is the world's largest sculpture park made by a single artist. Frogner Park is the most popular tourist attraction in Norway, with between 1 and 2 million visitors each year,[5] and is open to the public at all times. Frogner Park and the Vigeland installation (Norwegian: Frognerparken og Vigelandsanlegget) was protected under the Heritage Act on 13 February 2009 as the first park in Norway.[6][7]

History

In the middle of the 18th century Hans Jacob Scheel, then owner of the Frogner Manor, laid out a baroque garden adjacent to his new manor house. It was expanded by the people who followed him, starting with Bernt Anker (1746–1805) who bought Frogner in 1790 and expanded the main building. Benjamin Wegner took over the property in 1836 and he transformed the garden into a romantic park around 1840. Later, most of the arable land was sold to private developers.

Around one square kilometer remained when the City of Oslo bought the property in 1896 to secure space for further urban development. The municipal government decided around 1900 to make a park for recreation and sports. Frogner Stadium was opened near the road and the area near the buildings was opened to the public in 1904. Norwegian architect Henrik Bull designed the grounds and some of the buildings erected in Frogner Park for the 1914 Jubilee Exhibition. [8][9]

The municipal government subsequently decided that Gustav Vigeland's fountain and all his monuments and statues should be placed in the park. The area was ready for Gustav Vigeland fountain in 1924 and the final plan was released in 1932 by the city-council. Most of the statues depict people engaging in various typically human pursuits, such as running, wrestling, dancing, hugging, holding hands and so on. However, Vigeland occasionally included some statues that are more abstract, including one statue, which shows an adult male, fighting off a horde of babies.[10]

Would-be General and Chamberlain Hans Jacob Scheel (owner of Frogner from 1747) laid out a baroque garden around 1750

Would-be General and Chamberlain Hans Jacob Scheel (owner of Frogner from 1747) laid out a baroque garden around 1750 Industrialist Benjamin Wegner (owner of Frogner from 1836) transformed the garden into a romantic park around 1840

Industrialist Benjamin Wegner (owner of Frogner from 1836) transformed the garden into a romantic park around 1840 Landscape architect and city gardener Marius Røhne was a central person in the development of the park from the early 1900s

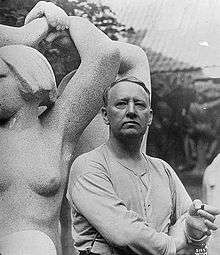

Landscape architect and city gardener Marius Røhne was a central person in the development of the park from the early 1900s Sculptor Gustav Vigeland created the sculpture arrangement in the centre of the present enlarged park from the 1920s until his death in 1943

Sculptor Gustav Vigeland created the sculpture arrangement in the centre of the present enlarged park from the 1920s until his death in 1943

Manor house

The manor buildings are located in the southern part of the park. The buildings in Danish country house style were built in the 1750s when Hans Jacob Scheel took over the property. After Bernt Anker, who was Norway's richest man, took over the estate in 1790, the buildings were further extended, and the manor house became one of the most important meeting places of Norwegian high society. They were rebuilt again by the industrialist Benjamin Wegner, who became owner in 1836 and who moved the tower to the main building.

Under Wegner, some surrounding buildings were also built, the pavilion on the nearby height "Utsikten" (The View) and the coachman house at the main gate in front of the manor house. The pavilion was a wedding gift from Wegner to his wife Henriette Seyler, and was moved from Blaafarveværket in the 1830s. It is a classical octagonal round temple with colonnade. The ceiling is a painted replica in miniature of the dome of the Pantheon, Rome. In front of the main buildings is also a sundial built for Wegner.

Today, the manor buildings are occupied by Oslo City Museum.

Outside the manor buildings, there is also a café opened in 1918 (Frogner Park Café) and a restaurant opened in 1960 (Herregårdskroen, "the Manor House Restaurant").

Vigeland installation – the sculptures in Frogner Park

The Vigeland installation (Norwegian: Vigelandsanlegget), originally called the Tørtberg installation, is located in the present centre of Frogner Park. It is the name of the arrangement of sculptures and not of an area as such, as the entire park is called Frogner Park.[3] The Vigeland installation in Frogner Park is sometimes referred to as "Vigeland Park," but this name has no official status, is not commonly used in Oslo and is considered inaccurate; the director of Oslo Museum Lars Roede said "Vigeland Park" "doesn't really exist" and is "the name of the tourists," as opposed to "Oslo natives' more down-to-earth name, Frogner Park."[3] The legal name of the entire park in accordance with the Place Name Act (stadnamnlova) is Frognerparken (Frogner Park).[11] The sculpture installation was, as part of Frogner Park, protected under the Heritage Act on 13 February 2009 under the name Frogner Park and the Vigeland installation (Norwegian: Frognerparken og Vigelandsanlegget), enshrining its name Vigelandsanlegget in law.[6]

The sculpture area in Frogner Park covers 80 acres (320,000 m2) and features 212 bronze and granite sculptures, all designed by Gustav Vigeland. The Bridge was the first part to be opened to the public, in 1940. The Bridge forms a 100 metre (328 ft)-long, 15 metre (49 ft)-wide connection between the Main Gate and the Fountain, lined with 58 sculptures, including one of the park's more popular statues, Angry Boy (Sinnataggen). Visitors could enjoy the sculptures while most of the park was still under construction. At the end of the bridge lies the Children’s Playground, a collection of eight bronze statues showing children at play.

Most of the statues in the park are made of Iddefjord granite.[12]

Originally designed to stand in Eidsvolls plass in front of the Parliament of Norway, the bronze Fountain (Fontenen) is adorned with 60 individual bronze reliefs, and is surrounded by an 1800 square metre black and white granite mosaic.

The Vigeland installation's granite and wrought iron Main Gate also serves as the eastern entrance to Frogner Park from Kirkeveien. From there an 850 m (2,790 ft) long axis leads west through the Bridge to the Fountain and the Monolith, and ends with the Wheel of Life. The Main Gate consists of five large gates, two small pedestrian gates and two copper-roofed gate houses, both adorned with weather vanes. It was designed in 1926, redesigned in the 1930s and erected in 1942. It was financed by a Norwegian bank.

The Monolith Plateau is a platform in the north of Frogner Park made of steps that houses the Monolith totem itself. 36 figure groups reside on the elevation, representing a “circle of life” theme. Access to the Plateau is via eight wrought iron gates depicting human figures. The gates were designed between 1933 and 1937 and erected shortly after Vigeland died in 1943.

At the highest point in Frogner Park lies the park's most popular attraction, the Monolith (Monolitten). The name derives from the Latin word monolithus, from the Greek μονόλιθος (monolithos), μόνος meaning "one" or "single" and λίθος "stone", and in this case is a genuine monolith, being fabricated from one piece of solid stone. Construction of the massive monument began in 1924 when Gustav Vigeland modelled it in clay in his studio in Frogner. The design process took ten months, and it is supposed that Vigeland used sketches drafted in 1919. A model was then cast in plaster.[13]

In the autumn of 1927 a block of granite weighing several hundred tons was delivered to the park from a quarry in Halden. It was erected a year later and a wooden shed was built around it to keep out the elements. Vigeland’s plaster model was erected next to it for reference. Transferring the design began in 1929 and took three masons 14 years to accomplish. The Monolith was first shown to the public at Christmas 1944, and 180,000 people crowded into the wooden shed to get a close look at the creation. The shed was demolished shortly afterwards. The Monolith towers 14.12 metres (46.32 ft) high and is composed of 121 human figures rising towards the sky.

At the end of the installation's axis there is a sundial, forged in 1930 (there is also an 1830s sundial outside the manor house in the south of the park), and finally the Wheel of Life stone sculpture, carved 1933–1934. The wheel depicts four adults, a child and a baby (the baby and child are on opposite sides).

The latest addition to the park is a statue titled Surprised (Overrasket), originally completed in plaster in 1942 only months before one of the models for the work, Austrian refugee Ruth Maier, was sent to Auschwitz and killed. A bronze cast made in 2002 is now installed in the park.[14][15][16]

Frogner Park with the Vigeland installation seen in the centre

Frogner Park with the Vigeland installation seen in the centre The monolith

The monolith Frogner Pond seen from the main bridge

Frogner Pond seen from the main bridge Frogner park Pond during winter

Frogner park Pond during winter The central bridge during winter

The central bridge during winter Frogner Park

Frogner Park

Sports and bathing facilities

On the outskirts of Frogner Park is Frognerbadet (Frogner Baths), which opened in 1956. Old Frogner Stadium opened in 1901 and was the city's main arena for skating. In 1914 the current Frogner Stadium was built right next to the old stadium. At the site of the old Frogner Stadium, there are now tennis courts.

In popular culture

- The book The Doomsday Key written by author James Rollins has scenes in Frogner Park

- The Norwegian movie Elling features a scene in which the sex-obsessed Kjell-Bjarne admires the sculptures of the park with Elling.

- The science fiction novel Mockymen by Ian Watson utilizes the park as a plot point.

- The song "Vigeland's Dream"' on Eleanor McEvoy's album Out There describes a walk in the park.

- The science fiction novella The State of the Art by Iain M Banks includes a walk in the park by the main characters.

- In the detective thriller The Leopard, part of the Harry Hole series, Frogner Park is the scene of a sensational murder case.

- In the TV series The Love Boat, some of the crew visited and saw the Vigeland sculptures in Frogner Park in a two-episode special.[17]

- The 2017 film The Snowman features scenes in the park.

References

- "Frogner Park. Interactive Google Street View image and map". Geographic.org/streetview. Retrieved 2017-07-02.

- Frogner Park (Visitnorway.com)

- Einar Solvoll (2008-11-14). "Aften spør for deg". Aftenposten.

Vigelandsparken finnes egentlig ikke! Vigelandsanlegget er en del av Frognerparken, som er det store restarealet av Frogner hovedgård [...] turistenes Vigelandsparken [...] Oslo-folkets mer jordnære navn, Frognerparken

- Frognerparken (Frogner Park's friends) Archived 2010-05-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Om Frognerparken Archived 2012-06-22 at the Wayback Machine, Frognerparkens Venner

- Frognerparken og Vigelandsanlegget Archived 2014-12-20 at the Wayback Machine, Kulturminnesøk

- Miljøverndepartementet: «Frognerparken fredet» besøkt 13 February 2009

- Welcome to Frogner Park (Agency for Outdoor Recreation and Nature Management)

- Jubileumsutstillingen i Kristiania, 1914 (Geir Tandberg Steigan)

- History of Frogner Park (Aktiv I Oslo.no) Archived 2011-06-02 at the Wayback Machine

- "Frognerparken," in Sentralt stedsnavnregister (The National Place Name Register), Norwegian Mapping and Cadastre Authority

- Inge, Bryhni; Askheim, Svein. "Iddefjordsgranitt". Store Norske Leksikon (in Norwegian). Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- Monolitten (Vigeland-museet)

- NRK P2 7 August 2002 (read online 3 September 2012)

- http://www.aftenposten.no/amagasinet/article2042118.ece Archived 2007-10-14 at the Wayback Machine Aftenposten om Ruth Maier, Norges «Anne Frank»

- http://www.vigeland.museum.no/no/frognerparken/andre-skulpturer%5B%5D Accessed 3 September 2012

- source: viewed these episodes on MeTV network

Further reading

- Roede, Lars (2012). Frogner hovedgård; bondegård, herskapsgård, byens gård, Pax forlag, ISBN 8253034962

- Sanstøl, Jorunn (ed.) (1996). Frognerparken – fra dyrket mark til byens park. Byminner, No. 1/2–96, Oslo Bymuseum/Frognerparkens venner

- Wikborg, Tone (1985). Gustav Vigeland – His Art and Sculpture Park (Oslo: Aschehoug) ISBN 82-03-16150-2

- Stępnik, Małgorzata. Modernist sculpture parks and their ideological contexts – on the basis of the oeuvres by Gustav Vigeland, Bernhard Hoetger and Einar Jónsson, „The Polish Journal of Aesthetics”, No. 47 (4/2017), pp. 143–169. e-ISSN 2353-723X / p-ISSN 1643-1243

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to |

- Frognerparkens venner (Friends of Frogner Park)

- Oslo City Museum

- Vigeland Sculpture Arrangement and the Vigeland Museum