Free City of Cracow

The Free, Independent, and Strictly Neutral City of Cracow[lower-alpha 1] with its Territory (Polish: Wolne, Niepodległe i Ściśle Neutralne Miasto Kraków z Okręgiem), more commonly known as either the Free City of Cracow or Republic of Cracow (Polish: Rzeczpospolita Krakowska, German: Republik Krakau), was a city republic created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815, which included the city of Kraków and its surrounding areas.

Free, Independent, and Strictly Neutral City of Cracow with its Territory Wolne, Niepodległe i Ściśle Neutralne Miasto Kraków z Okręgiem | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1815–1846 | |||||||||

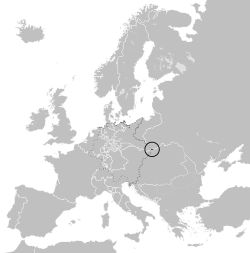

Location of the Free City of Cracow within Europe | |||||||||

Territory of the Free City of Cracow (orange) and its three neighbours (Kingdom of Prussia, Austrian Empire and Russian Empire) | |||||||||

| Status | Protectorate of Austria, Prussia and Russia | ||||||||

| Capital | Kraków | ||||||||

| Common languages | Polish (official), Yiddish, German | ||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic, Judaism | ||||||||

| Government | Constitutional republic | ||||||||

| President of the Senate | |||||||||

| Legislature | Assembly of Representatives (Cracow) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 3 May 1815 | |||||||||

| 29 November 1830 | |||||||||

• Kraków Uprising | 16 November 1846 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1815 | 1,164 km2 (449 sq mi) | ||||||||

| 1843 | 1,164 km2 (449 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1815 | 95,000 | ||||||||

• 1843 | 146,000 | ||||||||

| Currency |

| ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

It was jointly controlled by its three neighbours (Russia, Prussia, and Austria), and was a centre of agitation for an independent Poland. In 1846, in the aftermath of the unsuccessful Kraków Uprising, the Free City of Cracow was annexed by the Austrian Empire.[1] It was a remnant of the Duchy of Warsaw, which was partitioned between the three states in 1815.

The Free City of Cracow was an overwhelmingly Polish-speaking city-state; of its population 85% were Catholics, 14% were Jews while other religions comprised less than 1%. The city of Kraków itself had a Jewish population reaching nearly 40%, while the rest were almost exclusively Polish-speaking Catholics.[2]

History

The Free City was approved and guaranteed by Article VII of the Treaty between Austria, Prussia, and Russia of 3 May 1815.[3] The statelet received an initial constitution at the same time,[3] revised and expanded in 1818, establishing significant autonomy for the city. The Jagiellonian University could accept students from the partitioned territory of Poland. The Free City thus became a centre of Polish political activity on the territories of partitioned Poland.

During the November Uprising of 1830–31, Kraków was a base for the smuggling of arms into the Russian-controlled Kingdom of Poland. After the end of the uprising the autonomy of the Free City was severely restricted. The police were controlled by Austria and the election of the president had to be approved by all three powers. Kraków was subsequently occupied by the Austrian army from 1836 to 1841. After the unsuccessful Kraków uprising of 1846, the Free City was annexed by Austria on 16 November 1846 as the Grand Duchy of Cracow.

| Part of a series on |

| Polish statehood |

|---|

|

| Poland |

|

| Poland portal |

- Granting of the constitution of the Free City of Cracow, 1815-1818. (Painting from the mid-19th century).

- Galician slaughter (Polish "Rzeź galicyjska") by Jan Lewicki (1795-1871).

Geography, population, and economy

The Free City of Cracow was created from the southwest part of the Duchy of Warsaw (part of the former Kraków Department on the left bank of the Vistula river). The territory of the city was at its least 1164–1234 km² (sources vary). It bordered the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia and the Austrian Empire. It comprised the city of Kraków and its environs; the other settlements in the area administered by the Free City included 224 villages and three towns (Chrzanów, Trzebinia and Nowa Góra).

In 1815, its population was 95,000; as of 1843, it had a population of 146,000. 85% of them were Catholics, 14% Jews, while other religions comprised 1%. The most notable szlachta family was the Potocki family of magnates, who had a mansion in Krzeszowice.

The Free City was a duty-free area, allowed to trade with Russia, Prussia and Austria. In addition to no duties, it had very low taxes, and various economic privileges were granted by the neighbouring powers. As such, it became one of the European centres of economic liberalism and supporters of laissez-faire, attracting new enterprises and immigrants, which resulted in impressive growth of the city. Weavers from Prussian Silesia had often used the Free City as a contraband outlet to avoid tariff barriers along the borders of Austria and the Kingdom of Poland, but with Austria's annexation of the Free City came a significant drop in Prussian textile exports.[4]

Free City of Cracow, 1815-1846.

Free City of Cracow, 1815-1846. 5 groszy coin displaying the coat of arms of the Free City, and 1 złoty coin of 1835.

5 groszy coin displaying the coat of arms of the Free City, and 1 złoty coin of 1835.

Politics

The statelet received an initial constitution in 1815 which had mainly been devised by Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski. The constitution was revised and expanded in 1818, establishing significant autonomy for the city. Legislative power was vested in the Assembly of Representatives (Izba Reprezentantów), and the executive power was given to a Governing Senate.

In 1833, in the aftermath of the November Uprising and the foiled plan by some Polish activists to start an uprising in Kraków, the partitioning powers issued a new, much more restrictive constitution: the number of senators and deputies was lowered and their competences limited, while the commissars of the partitioning powers had their competences expanded. Freedom of the press was also curtailed. In 1835 a secret treaty between the three partitioning powers presented a plan in which in case of additional Polish unrest, Austria was given the right to occupy and annex the city. That would take place after the Kraków Uprising of 1846.

The law was based on the Napoleonic civil code and French commercial and criminal law. The official language was Polish. In 1836 the local police force was disbanded and replaced by Austrian police; in 1837 the partitioning powers curtailed the competences of the local courts which refused to bow down to their demands.

The Free City of Kraków was the first purely republican government in the history of Poland.

See also

Notes

- The Polish variant of Kraków is occasionally retroactively applied in English to the historical Free City.

References

- Degan 1997, p. 378.

- Censuses of the Austro-Hungarian Statistical Central Commission, cited in Anson Rabinbach, The Migration of Galician Jews to Vienna. Austrian History Yearbook, Volume XI, Berghahn Books/Rice University Press, Houston 1975, p. 46/47 (table III)

- Hertslet 1875, p. 127.

- Feuchtwanger 1970, p. 157.

References

- Degan, Vladimir Đuro (1997), Developments in International Law: Sources of Internat'l, Developments in International Law Series, 27 (illustrated ed.), Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, p. 378, ISBN 9789041104212

- Feuchtwanger, E. J. (1970), Prussia: Myth and Reality, Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, p. 262, ISBN 0-85496-108-9

- Hertslet, Edward (1875), "No.15", The map of Europe by treaty; showing the various political and territorial changes which have taken place since the general peace of 1814, London: Butterworths. (No. 12), p. 127

Further reading

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

![]()

- EB staff, "Republic of Cracow", Encyclopædia Britannica online, retrieved 12 December 2012