Fredrik Magnus Piper

Fredrik Magnus Piper (1746–1824) was a Swedish landscape architect and architect. He introduced the theory and practice of the English landscape garden to Sweden.[1][2] Among his tangible contributions are the creation of the general plan for the royal park Hagaparken in Stockholm, part of the current Royal National City Park, and contributions to the development of the park at Drottningholm Palace.[1]

Biography

Fredrik Magnus Piper was a nobleman but came from a bourgeois family, his father having been ennobled only in 1776. He studied mathematics and hydraulics at Uppsala University between 1764 and 1766, after which he went on to specialise in engineering in a special school in Trollhättan and at the naval base in Karlskrona. In Karlskrona he befriended Admiral Fredrik Henrik af Chapman, who supported his artistic ambitions. After continuing his studies in Stockholm, partly under the tutelage of the architect Carl Fredrik Adelcrantz, he went on a study trip to the United Kingdom. He left Sweden in 1773, only to return in 1780.[3]

Aided by a letter of recommendation by af Chapman, Piper was introduced to William Chambers and to institutions such as the Royal Academy. During his stay in England, Piper was introduced to the then new theory and practice of English landscape gardens. He made well-executed drawings of The Leasowes, Painshill and Stourhead, and worked for a while at Chambers' firm. He later left England and continued his studies in France and Italy. In France he studied the gardens of André Le Nôtre and in Italy he made visits to the gardens at Villa Lante, Villa Doria Pamphili and Villa Aldobrandini. He returned briefly to England where he married in 1780, and then finally went back to Sweden.[3][4] Chambers was unhappy that Piper had left England, writing to Admiral af Chapman to complain that he had not been consulted sufficiently. It appears, however, that Piper always held Chambers in high regard as "his first art teacher".[5]

In Sweden he was quickly promoted and given prestigious commissions by King Gustav III, despite having an undiplomatic and overly straightforward demeanour. Most of his work was executed during the reign of Gustav III, who strongly supported Piper. After the assassination of the king in 1792, his activity declined.[3]

Works

One of the first works carried out by Piper after his return to Sweden was a design for the park at Drottningholm Palace near Stockholm. His ideas were in this case widely disregarded, as the king had his own ideas for the re-shaping of the park.[3] His design, however, did include copper tents and Turkish pavilions, which Piper is credited with.[6]

Instead, Haga park outside Stockholm became Piper's chef d'oeuvre. He was given a wide mandate by the monarch to pursue his own ideas. He repeated the idea of the copper tent and Turkish pavilion,[6] but here he introduced an accomplished form of the English landscape garden. Among his innovations were the introduction of great, oval-shaped lawns, so-called pelouses, a sophisticated deployment of monuments and pavilions within the landscape, and a radical integration of architecture into the landscape without any intermediary elements such as steps or gravel borders. Although the plans for the park were not executed in their entirety, the park still largely reflects Piper's general plan.[3]

Piper also produced designs for several other parks, both private and public, some of which still exist, e.g. Hogland park in Karlskrona and Bellevue park in Stockholm. As a landscape architect, Piper has been described as skilful and open-minded; he was able to produce both radical and more traditional types of parks with equal skill.[3]

Piper was also active as an architect; he designed the main building of Bjärka-Säby Castle in about 1796 and Listonhill villa on Djurgården (Stockholm) in 1790 and 1791.[7] He wrote but never published a theoretical treatise on landscape gardening, and produced other theoretical works such as ideal plans.[3]

Gallery

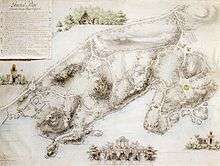

General plan for Drottningholm Palace park

General plan for Drottningholm Palace park Design for a temple of Neptune in Haga park (not executed)

Design for a temple of Neptune in Haga park (not executed) Design for a pyramid-shaped pavilion in Haga park (not executed)

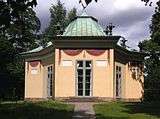

Design for a pyramid-shaped pavilion in Haga park (not executed) The Turkish pavilion, designed by Piper, in Haga park

The Turkish pavilion, designed by Piper, in Haga park Villa Listonhill, Djurgården (Stockholm)

Villa Listonhill, Djurgården (Stockholm)

References

- "Fredrik Magnus Piper". Lexikonett Amanda (in Swedish). Kultur1. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- Carlquist, Gunnar, ed. (1960). Svensk Uppslagsbok (in Swedish). 22. Malmö: Förlagshuset Norden AB. p. 1081.

- Olausson, Magnus (2004). Beskrifning öfwer idéen och general-plan till en ängelsk lustpark. Stockholm.

- "A Biography of Fredrik Magnus Piper". gardenvisit.com. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- Harris et al (Ed.), John (1996). Sir William Chambers: Architect to George III. Couutald. p. 16. ISBN 0300069405.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Treib, Marc (2011). Meaning in Landscape Architecture and Gardens. p. 129. ISBN 978-1136804595.

- "Fredrik Magnus Piper". Oxford Reference. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

External links