Frederick Law Olmsted Jr.

Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. (July 24, 1870 – December 25, 1957) was an American landscape architect and city planner known for his wildlife conservation efforts. He had a lifetime commitment to national parks, and worked on projects in Acadia, the Everglades and Yosemite National Park. He gained national recognition by filling in for his father on the Park Improvement Commission for the District of Columbia beginning in 1901, and by contributing to the famous McMillan Commission Plan for redesigning Washington according to a revised version of the original L’Enfant plan.[3] Olmsted Point in Yosemite and Olmsted Island at Great Falls of the Potomac River in Maryland are named after him.

Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 24, 1870 Staten Island, New York |

| Died | December 25, 1957 (aged 87)[1] |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Roxbury Latin School Harvard University |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Parent(s) | Frederick Law Olmsted Mary Cleveland Perkins |

| Awards | Pugsley Medal (1953) |

| Practice | Olmsted Brothers |

| Buildings | Biltmore Estate |

| Projects | Washington, D.C.: National Mall; Jefferson Memorial; White House grounds; Rock Creek Park. Others: Bok Tower Gardens; Forest Hills Gardens; Leimert Park, Los Angeles, Lake Wales, Florida |

The son of Frederick Law Olmsted Sr., he and his older half-brother John C. Olmsted created Olmsted Brothers about 1896 as a successor firm to their father's firm. They had both worked with him before his retirement. Soon after his father's death, Olmsted stopped using the suffix "Jr." Works attributed to Frederick Law Olmsted after about 1896 are those of this son.

Early life and education

Olmsted was born in 1870 on Staten Island, New York, the youngest surviving child of three born to Frederick Law Olmsted, a landscape architect and journalist, and Mary Cleveland (née Perkins). Their first son died in infancy. Frederick Jr. had an older sister and three older half-siblings.

His mother had been married before, to Frederick's brother, and widowed after John Olmsted died of tuberculosis. His father married the widowed Mary a couple of years later and adopted their three children. Among them was John Charles Olmsted, born in 1852, and a younger sister and brother. [4][5]

After graduating from the Roxbury Latin School in 1890,[6] Olmsted began his design career as an apprentice to his noted father. Olmsted worked early on two significant projects: the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, and the largest privately owned home in the United States—the George Vanderbilt estate in North Carolina, known as the Biltmore Estate.

After this apprenticeship, Olmsted entered Harvard College. He earned his bachelor's degree in 1894.

Career

After graduation, Olmsted became a partner in his father's Brookline, Massachusetts landscape architecture firm in 1895. His older brother John was already working there. Shortly thereafter, his father retired. Olmsted and John quickly took over leadership of the firm. For the next half-century, the Olmsted Brothers firm completed thousands of landscape projects nationwide.

In 1900, Olmsted returned to Harvard to teach. He also established the school's first formal training program in landscape architecture.

In 1901, Olmsted was appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt as a member of the Senate Park Improvement Commission for the District of Columbia, commonly known as the McMillan Commission. He joined other notable architects and designers such as Daniel H. Burnham, Charles F. McKim and Augustus Saint-Gaudens, who were charged to "restore and develop the century-old plans of Major L'Enfant for Washington and to fit them to the conditions of today." Their resulting McMillan Plan was approved and has guided federal planning in the District through review of projects and designs by the National Capital Planning Commission.

In 1910, he was approached by the American Civic Association for advice on the creation of a new bureau of national parks. This initiated six years of correspondence, including this letter to the president of the Appalachian Mountain Club, dated January 19, 1912:

The present situation in regard to the national parks is very bad. They have been created one at a time by acts of Congress which have not defined at all clearly the purposes for which the lands were to be set apart, nor provided any orderly or efficient means of safeguarding the parks ... I have made at different times two suggestions, one of which was ... a definition of the purposes for which the national parks and monuments are to be administered by the Bureau.

Olmsted recommended the following for the mission, a statement preserved in the National Park Service Organic Act (1916):

To conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.

Olmsted married Sarah Hall Sharples on March 30, 1911. They had one child together.

By 1920, he had completed well-known projects such as plans for metropolitan park systems and greenways across the country. In 1928, while working for the California State Park Commission (now part of the California Department of Parks and Recreation), Olmsted completed a statewide survey of potential park lands that defined basic long-range goals and provided guidance for the acquisition and development of state parks.[7]

Under the leadership of John Charles Olmsted and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., the Olmsted Brothers firm employed nearly 60 staff at its peak in the early 1930s. As the last surviving family member in the firm, Olmsted retired in 1949.

Olmsted completed many important design projects in the nation's capital: the National Mall, Jefferson Memorial, White House grounds, and Rock Creek Park. These are now managed by the National Park Service. Olmsted also prepared the plan for Boston's metropolitan park system, including the Fenway; and a master plan for Cornell University in upstate New York. It featured a terrace-style 'master plan' layout, from which was constructed the large Arts Quad and Libe Slope. He took part in designing two early planned suburban communities: Forest Hills Gardens, Queens, in New York, and Roland Park, Baltimore, Maryland. In addition, he worked on the Bok Tower Gardens in Lake Wales, Florida.

Olmsted also worked internationally. His design for the Caracas Country Club (mid 1920s) in Venezuela drew from the natural scenery of the area.[8] In the early 21st century, the Caracas Country Club is the only place in the city where it is possible to have a sense of the valley's original natural landscape. In the 1920s, he was asked to adapt the lands associated with the former haciendas Blandín, Lecuna, El Samán and La Granja into a residential golf club; Olmsted created a sensitive urban design and landscaping project.[8]

Professional and civic activities

A founding member and later president of the American Society of Landscape Architects, Olmsted was active in numerous other planning and design organizations and commissions, including the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, the National Capital Park and Planning Commission, the Baltimore Park Commission, the National Park Service Board of Advisers for Yosemite, the National Conference on City Planning, the American City Planning Institute, the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and the American Academy in Rome.

Legacy and honors

Olmsted received many awards and honors during his long career, among them the American Academy Gold Medal (1949) and the U.S. Department of the Interior Conservation Award (1956).[9]

In his later years, Olmsted worked to protect California's coastal redwoods. Redwood National Park's Olmsted Grove was dedicated to him in 1953, the same year in which he received the Pugsley Gold Medal.

Olmsted died while visiting friends in Malibu, California.[2] He is buried at Old North Cemetery in Hartford, Connecticut.

Projects

- Landscape design at Waveny Park,[10] New Canaan, Connecticut, 1912.

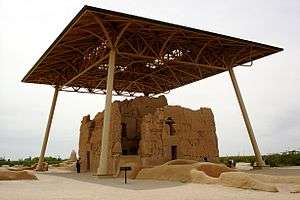

- Shelter at Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, 1932

- St. Francis Wood residential neighborhood located in southwestern San Francisco, California, c. 1914

- Fort Tryon Park, New York City, 1917–1935

- Caracas Country Club, Caracas, Venezuela, mid-1920s[11]

- Palos Verdes Estates, Los Angeles County, mid-1930s

- Governor Francis Farms neighborhood founded in 1838 in Warwick, Rhode Island. He designed many of the homes in that neighborhood in 1949.

References

- American Council of Learned Societies (1958). Dictionary of American Biography. Scribner. p. 485. ISBN 0-684-16226-1.

- "The Lasting Legacy of Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. Is Everywhere". 2008-11-18. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. pp. 501. ISBN 9780415252256.

- Witold Rybczynski, A Clearing in the Distance: Frederick Law Olmsted and America in the Nineteenth Century, Scribner, New York, 1999.

- Frederick Law Olmsted; Theodora Kimball Hubbard (1922). Frederick Law Olmsted, Landscape Architect, 1822-1903. G.P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 78–.

- F. Washington Jarvis, Schola Illustris: The Roxbury Latin School, 1645-1995, p. 344. Boston: David R. Godine, 1995. ISBN 1-56792-066-7.

- "A State Park System is Born". State of California. Retrieved 2007-07-28.

- Simon Romero, Sandra La Fuente P. contributor (27 December 2010). "A Venezuelan Oasis of Elitism Counts Its Days". The New York Times. p. A1 NY ed. Retrieved 2012-04-11.

- Thomas E. Luebke, ed., Civic Art: A Centennial History of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, 2013): Appendix B, p. 551.

- Kendall, Jane. "The Magic of Waveny". Archived from the original on 2009-11-16. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- Gómez, Hannia (2010-10-25). "Olmsted en Blandín". Desde la memoria urbana (in Spanish). Retrieved 2020-03-08.

- M. Christine Boyer, Manhattan Manners: Architecture and Style, 1850-1900. New York: Rizzoli, 1985. ISBN 0-8478-0650-2

![]()

![]()

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. |

- Works by Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. at Project Gutenberg

- www.olmsted.org

- FAQ: Frederick Law Olmsted Jr.