Fraoch Eilean, Loch Awe

Fraoch Eilean/Ejlean is a small island situated at the northern end of Loch Awe, a freshwater lake in Argyll and Bute, Scotland. It is notable for being the site of a medieval royal castle, now ruined, which was given into the keeping of Clan Macnaghten by Alexander III in 1267. [1]

| Gaelic name | Fraoch Eilean |

|---|---|

| Meaning of name | Heather Island |

| Location | |

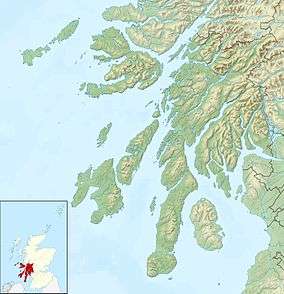

Fraoch Eilean Fraoch Eilean shown within Argyll and Bute | |

| OS grid reference | NN108251 |

| Coordinates | 56.380209°N 5.065834°W |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Loch Awe |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | Argyll and Bute |

Etymology

The name Fraoch Eilean means literally "heather island" in Scottish Gaelic, although Lord Archibald Campbell believes that the ordering of the words give the meaning more correctly as the "Isle of Fraoch".[2][3] Fraoch was a hero of Celtic mythology. Fruit that restored youth and cured hunger was said to hang from a Rowan tree growing on an island in Loch Awe. The tree was guarded by a serpent or dragon which was wrapped around the trunk.[4][5] Fraoch succeeded in stealing fruit from the tree, but when he was sent back to get the tree itself, the dragon pursued him. In the ensuing battle, both Fraoch and the dragon died. A cairn was raised on the spot where Fraoch fell and the island named in his honour.[4] This legend, a version of the Hesperides myth, is recounted in a Gaelic ballad, Bás Fraoich, which was collected by Jerome Stone, the schoolmaster at Dunkeld, and published in his metrical English translation in The Scots Magazine, January 1756.[6]

Geography

Fraoch Eilean is one of a group of small islands at the north end of Loch Awe. To the north of Fraoch Eilean lies Innischonain and to the south is Inishail.[7] Eilean Beith and Badan Tomain are smaller islets to the north east. Further to the north east beyond the headland of Rubha Duibhairt there is a crannóg or artificial island with a second to the east near the shores of Loch Awe.[7]

The island of Fraoch Eilean itself consists of two rocky eminences connected by a sand and shingle beach. The ruins of a castle occupy much of the eastern eminence.[5] Vitrified stone has been found on the island close to the ruins of the castle.[8]

The castle on Fraoch Eilean

History

The island has a strong strategic location given its position opposite the Pass of Brander at the northern end of Loch Awe. It commands a view towards the Firth of Lorn and the Atlantic, allowing for distant sightings of any invasionary force coming to Scotland from the sea.[9]

The island and castle on it belonged to the Scottish king Alexander III. The castle may have been one of the earliest stone fortifications in the county of Argyll and prior to becoming a royal castle may have been occupied by the MacDougalls.[4] In 1267, as part of a campaign to secure allies in the west of Scotland following the Battle of Largs, the king granted the "Hereditary Keepership of the Royal Castle on the Island of Fraoch Eilean" (Innes Fraoch or Frechelan as it was called at the time) to the family of Sir Gilchrist MacNauchtan.[10][11] The Clan MacNauchtan were to keep the castle repaired and secure (at the king's expense) such that Alexander could be suitably received when visiting the area. Local tradition said that the rental was a ball of snow.[4][12] It is thought that this rent could have been paid during any season given the fact that the high mountain Ben Cruachan was located nearby.[12] The charter document bearing MacNauchtan's signature is said to be one of the oldest surviving documents in the National Archives of Scotland.[9] "Fraoch Eilean" was the war-cry of Clan MacNauchtan.[4]

There is however, reason to suspect that the charter documenting the grant is spurious.[13] Be that as it may, such a grant fits into the context of ongoing consolidation of Scottish royal power in the western fringes of the kingdom in the years following the Treaty of Perth. The earliest phase of construction at the castle site dates to the twelfth- and thirteenth-centuries, and the castle's remains dating from this period closely resemble the earliest remains of Castle Sween.[14]

During the 14th century the castle passed into the hands of the Campbell clan who already held a number of other castles along Loch Awe including Kilchurn Castle and Inishail.[15] In 1745 a Macnachtan retook the castle from the Campbells. It was refurbished for the use of Charles Edward Stuart, Bonnie Prince Charlie, who it was thought may have planned to pass through the area following his landing at Glenfinnan.[4] It is thought that the castle was finally abandoned at some point before 1769.[16]

Archeology

The ruins of the castle stand at the high point of the island, on the eastern rocky eminence. Archaeologists have identified remains from four different time periods. The earliest of these structures dates from the 13th century and comprises a stone hall-house which stands on the east side of the site.[16] Now ruined, it measured 80 feet (24 m) by 30 feet (9.1 m).[7] At this time the rest of site would have been populated by wooden and turf out-buildings. This area was later enclosed by a stone curtain wall which included both a tower and a gateway.[16]

At the beginning of the 17th century, and sometime after the stone hall had been abandoned, a much smaller structure was built at the north-east corner of the hall. The remaining area of the hall, now roofless, was used as an inner courtyard.[16] Finally, later in the 17th century, the small hall-house was enlarged during a final stage of reconstruction. The remaining walls have an average height of 4.6 metres (15 ft), whilst the north wall is the most intact and reaches a height of 9.0 metres (29.5 ft).[16]

Notes

- The full text of the charter is printed in Angus I. Macnaghten, The Chiefs of Clan Macnaghtan and Their Descendants, 1951, reviewed in The Scottish Historical Review 32 No. 114, Part 2 (October 1953:192f).

- Campbell, Archibald (1885). Records of Argyll; legends traditions, and recollections of Argyllshire Highlanders, collected chiefly from the Gaelic, with notes on the antiquity of the dress, clan colours, or tartans, of the Highlanders. Edinburgh: W. Blackwood. p. 493.

- Iain Mac an Tailleir. "Placenames" (PDF). Pàrlamaid na h-Alba. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2008-04-10. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- "From Loch Awe to Dunderawe" Ancestry.com. Retrieved 23 August 2009.

- "Loch Awe from Fraoch". Am Baile. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- Robert P. Fitzgerald, "The Style of Ossian", Studies in Romanticism 6.1 (Autumn 1966:22-33) p. 25 (date given "1758"); Tom Peete Cross, reviewing P. Van Tieghem, Ossian en France, in Modern Philology 16.8 (December 1918:439-448) p 445f gives corrected date: Cross notes that Stone substituted Albin for Fraoch as more euphonious in English .

- Macnaughton, Ken (Sep 2009). "Fraoch Eilean and Dubh Loch" (PDF). clanmacnaughton.net. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- "Fraoch Eilean, Loch Awe". Scotlands Places. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- Macnaughton, Ken (29 Jan 2009). "King Alexander III and the Macnachtan Charter" (PDF). clanmacnaughton.net. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- Oliver and Boyd's guide to the West Highlands. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. 1860. p. 11.

- Adam, Frank (1970). The Clans, Septs and Regiments of the Scottish Highlands. Edinburgh: Johnston and Bacon. p. 97. ISBN 0-7179-4500-6.

- Campbell, Archibald (1885). Records of Argyll; legends traditions, and recollections of Argyllshire Highlanders, collected chiefly from the Gaelic, with notes on the antiquity of the dress, clan colours, or tartans, of the Highlanders. Edinburgh: W. Blackwood. p. 495.

- Neville; Simpson (2012) p. 105 (§65); McDonald (1997) pp. 238–239.

- McDonald (1997) pp. 238–239.

- Campbell, Alistair (2002). A History of Clan Campbell. 2. Edinburgh University Press. p. 104. ISBN 1-902930-18-5.

- "Site record for Fraoch Eilean". Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

References

- McDonald, RA (1997). The Kingdom of the Isles: Scotland's Western Seaboard, c. 1100–c. 1336. Scottish Historical Monographs (series vol. 4). East Linton: Tuckwell Press. ISBN 978-1-898410-85-0.

- Neville, CJ; Simpson, GG, eds. (2012). The Acts of Alexander III King of Scots 1249–1286. Regesta Regum Scottorum (series vol. 4, part 1). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978 0 7486 2732 5. Accessed via Questia (subscription required).

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fraoch Eilean. |