Franz Neuhausen

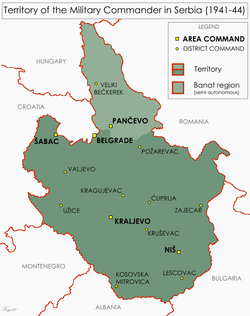

Franz Neuhausen (13 December 1887 – 14 April 1966) was a wealthy industrialist who became the special plenipotentiary for economic affairs in the Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia during most of the German military occupation of that region of the partitioned Kingdom of Yugoslavia during World War II. He worked as a representative of Germany and the Nazi Party in Belgrade throughout the 1930s, during which he amassed a huge fortune. As a close friend and personal favourite of Reichsmarshall Hermann Göring, he became Göring's direct representative for the Four Year Plan in the occupied territory, and was its virtual economic dictator from April 1941 until August 1944. On 18 October 1943 he succeeded Harald Turner as the Chief of the Military Administration in Serbia, and he continued to fulfill both roles until late August 1944.

NSFK-Obergruppenführer Franz Neuhausen | |

|---|---|

Franz Neuhausen in NSFK uniform | |

| Nickname(s) | Fat Franz[1] |

| Born | 13 December 1887 Merzig, German Empire |

| Died | 14 April 1966 (aged 78) Munich, West Germany |

| Allegiance | |

| Rank |

|

| Commands held | Chief of the Military Administration in Serbia |

| Awards | Knights Cross to the War Merit Cross |

Neuhausen was considered "sleazy and unscrupulous" and "notoriously corrupt". After complaints by senior Nazi officials in south-east Europe he was arrested and sent to a concentration camp, but survived to be captured by United States authorities. He was handed over by the US to the Yugoslav authorities after the war, and was sentenced to 20 years imprisonment. He was released in 1953 and died in Munich, West Germany in 1966.

Early life and inter-war years

Neuhausen was born on 13 December 1887 in the town of Merzig in the Rhine Province of the German Empire.[2] Nothing is known of his family or life before World War I, and he was a pilot in the German Air Force during that war.[3] In the inter-war period he reached the rank of Gruppenführer (major general) in the National Socialist Flyers Corps (German: Nationalsozialistisches Fliegerkorps, NSFK) which was a paramilitary Nazi Party organisation similar to the Sturmabteilung or SA.[4] He was stationed in Belgrade from 1931 onwards, first as the manager of the German Transportation Office, then as the official representative or party attache (Landesgruppenleiter) of the Nazi Party in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and finally as the German consul-general, with the rank of Consul-General Major of the Luftwaffe.[4] It is likely that he fulfilled both political and economic intelligence work in Yugoslavia throughout the 1930s. He had effective networks in both government and political circles and kept himself well informed about political and economic conditions, becoming a wealthy industrialist in the process.[3] With the assistance of his close friend[5] Reichsmarshall Hermann Göring he obtained shares in a range of mining and metal industries through dubious transactions. As a result of such deals, Neuhausen was arrested by the Gestapo several times but Göring interceded on his behalf on each occasion to ensure that the serious charges were downgraded. In return, Neuhausen provided Göring with foreign currency, and when he attended the Reichsmarshall's birthday party each year he gave Göring a 30-pound (14 kg) bar of gold or silver. Göring used this money to amass a huge collection of artworks and jewelry at his country estate, Carinhall.[6] As consul-general, Neuhausen negotiated the purchase of the huge Bor copper mines from the defeated French in 1940, and subsequently became chairman of the board of the new German company that operated the mines, Bor Kupferbergwerke und Hütten A.G. in Belgrade.[7]

Role in the occupied territory

Promoted to NSFK-Obergruppenführer,[8] Neuhausen was initially appointed by Göring as plenipotentiary general for economic affairs (Generalbevollmächtigte für die Wirtschaft) in the Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia,[9] but his role soon expanded to encompass plenipotentiary responsibility for the Four Year Plan in the occupied territory. On 9 December 1942, Neuhausen was also appointed to the important role of plenipotentiary for metal ore production in south-east Europe,[10] which was initially limited to the occupied territory and the areas of Yugoslavia annexed by Bulgaria,[3] and he was also empowered as plenipotentiary for labour in the occupied territory. Soon after the military administration began, Neuhausen appointed commissioners through whom he controlled the Serbian National Bank and other key economic and financial enterprises. In March 1943 Neuhausen's responsibilities for metals ore production were extended to German-occupied Greece, and after the Italian surrender that September, to the previously Italian-occupied parts of Greece and Albania. In October 1943, the Germans simplified their military administration, and on 18 October 1943 his existing roles were combined with the key role of Chief of the Military Administration (Militärverwaltungschef).[3] He remained the chairman of the Bor mining company, which in July 1943 brought in 6,200 Jewish forced labourers from Hungary and territories it had occupied to alleviate the shortage of manpower to work the mine.[11][12] At the mines the labourers were under the supervision of the SS and worked in knee-deep water for 12-hour shifts.[12] Neuhausen was also chair of the German banking corporation Bankverein für Serbien in the occupied territory, as well as several other important companies. Economically, the occupied territory was very important to the Germans as a source of metals, minerals, coal and food.[13] Neuhausen was a powerful figure who had complete control of the economy and state finances of the occupied territory, and successfully exploited them to make a significant contribution to the German war effort.[14][15]

Rivalry and arrest

The presence in Belgrade of direct representatives of senior Nazi officials such as Himmler and Göring meant there were often competing interests at work. As plenipotentiary for economic affairs and a "favourite" of Göring,[16] Neuhausen acted as a virtual economic dictator on the Reichsmarshall's behalf in the occupied territory, squeezing the maximum amount of resources out of the local economy to feed the German war machine. Neuhausen was described as being "notoriously corrupt"[5] and "sleazy and unscrupulous",[16] and had numerous disagreements with other senior officials of the occupation regime regarding the extent of his jurisdiction. In particular, he strenuously opposed attempts by Foreign Affairs Envoy Hermann Neubacher to give more power to the Belgrade puppet government of Milan Nedić. Neubacher believed that Neuhausen was corrupt and that he had amassed a huge fortune while serving in Belgrade. After a series of complaints against him by the commander-in-chief southeast Europe Generalfeldmarschall (Field Marshal) Maximilian von Weichs and Neubacher himself, an agreement was reached with the Nazi Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop and Himmler, and Neuhausen was subsequently arrested for corruption in August 1944.[17] He was replaced as plenipotentiary for economic affairs by his mining chief Theo Keyser, and as Chief of the Military Administration in Serbia by Dr. Justus Danckwerts. Neuhausen spent five months in a concentration camp and, although Göring arranged his release,[5] and the award of the Knight's Cross of the War Merit Cross to him,[18] he still spent the remainder of the war in detention.[13][17]

After the war

After being captured by US forces he was handed over to the Yugoslav authorities at the end of the war, and although sentenced to 20 years imprisonment following a trial in October 1947, he was soon paroled,[1] then released in March 1953. Neuhausen died on 14 April 1966 in Munich, West Germany.[2]

Footnotes

- Der Spiegel & 47/1949.

- Völkl & Lengyel 1991, p. 52.

- Tomasevich 2001, p. 76.

- Kroener, Müller & Umbreit 2000, p. 96.

- Kurapovna 2010, p. 258.

- Alford 2012, pp. 17–18.

- Tomasevich 2001, p. 617.

- Gall 2006, p. 112.

- Hehn 1971, p. 350; Pavlowitch 2002, p. 141, official name of the occupied territory.

- Kroener, Müller & Umbreit 2003, p. 216.

- Kroener, Müller & Umbreit 2003, p. 39.

- Mojzes 2011, p. 91.

- Tomasevich 2001, pp. 76–77.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 320.

- Tomasevich 2001, p. 619.

- Hehn 2005, p. 109.

- Pavlowitch 2008, p. 230.

- Höttl 1997, p. 183.

References

Books

- Alford, Kenneth D. (2012). Hermann Göring and the Nazi Art Collection: The Looting of Europe's Art Treasures and Their Dispersal after World War II. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-8955-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gall, Lothar (2006). Der Bankier Hermann Josef Abs: eine Biographie (in German). Schnellbach: C.H.Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-54738-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hehn, Paul N. (2005). A Low Dishonest Decade: The Great Powers, Eastern Europe, and the Economic Origins of World War II, 1930-1941. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-1761-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Höttl, Wilhelm (1997). Einsatz für das Reich (in German). Schnellbach: Verlag Siegfried Bublies. ISBN 978-3-926584-41-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kroener, Bernard R.; Müller, Rolf-Dieter; Umbreit, Hans, eds. (2000), Germany and the Second World War, Volume 5: Organization and Mobilization of the German Sphere of Power. Part I. Wartime Administration, Economy, and Manpower Resources, 1939-1941., 5, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-822887-5CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kroener, Bernard R.; Müller, Rolf-Dieter; Umbreit, Hans, eds. (2003), Germany and the Second World War, Volume 5 : Organization and Mobilization of the German Sphere of Power. Part II. Wartime Administration, Economy, and Manpower Resources 1942-1944/5, 5, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-820873-0CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kurapovna, Marcia Christoff (2010). Shadows on the Mountain: the Allies, the Resistance, and the Rivalries that Doomed WWII Yugoslavia. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-08456-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mojzes, Paul (2011). Balkan Genocides: Holocaust and Ethnic Cleansing in the 20th century. Plymouth: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4422-0663-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2002). Serbia: The History Behind The Name. London: C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-476-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2008). Hitler's New Disorder: The Second World War in Yugoslavia. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-1-85065-895-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tomasevich, Jozo (1975). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941-1945. 1, The Chetniks. 1. San Francisco: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0857-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941-1945: Occupation and Collaboration. 2. San Francisco: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3615-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Völkl, Ekkehard; Lengyel, Zsolt K. (1991). Der Westbanat 1941–1944: die deutsche, die ungarische und andere Volksgruppen (in German). Munich: Trofenik. ISBN 978-3-87828-192-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Journals

- Hehn, Paul N. (1971). "Serbia, Croatia and Germany 1941–1945: Civil War and Revolution in the Balkans". Canadian Slavonic Papers. University of Alberta. 13 (4): 344–373. Retrieved 8 April 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Magazines

- "Neuhausen behielt seinen Kopf", Der Spiegel (in German), 47/1949, 17 November 1949