Franklinia

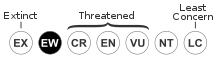

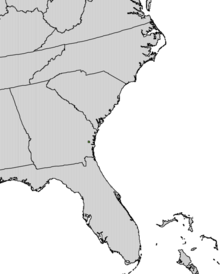

Franklinia is a monotypic genus in the tea plant family, Theaceae. The sole species in this genus is a flowering tree, Franklinia alatamaha, commonly called the Franklin tree, and native to the Altamaha River valley in Georgia in the southeastern United States. It has been Extinct in the wild since the early 19th century, but survives as a cultivated ornamental tree.

| Franklinia | |

|---|---|

| |

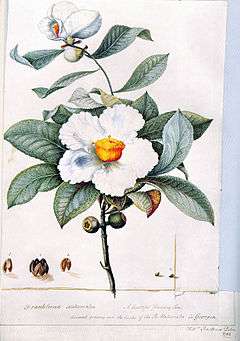

| Flower and leaves in autumn | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Ericales |

| Family: | Theaceae |

| Genus: | Franklinia W.Bartram ex Marshall[2] |

| Species: | F. alatamaha |

| Binomial name | |

| Franklinia alatamaha W.Bartram ex Marshall[2] | |

| |

| Natural range | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

In the past, some botanists have included Franklinia within the related genus Gordonia. The southeastern North American species Gordonia lasianthus (another tea species now extinct in the wild)[3] differs in having evergreen foliage, flowers with longer stems, winged seeds, and conical seed capsules. (Franklinia was often known as Gordonia pubescens until the middle of the 20th century.)

Franklinia is now thought to be closer in relation to the Asian genus Schima. Recent DNA studies and examinations of floral ontogeny in the Theaceae place Franklinia together with Gordonia and Schima in a subtribe.[4] Hybrid crosses have been produced between Franklinia alatamaha and Gordonia lasianthus, and between Franklinia alatamaha and Schima argentea.[5][6]

Description

Franklinia alatamaha is a deciduous large shrub or small tree growing to 10 m (33 ft) tall, but commonly 4.5–7.5 m (15–25 ft). It is commercially available for garden cultivation. It is prized for its lightly fragrant white flowers, similar to single white Camellia blossoms; the smell may remind some of orange blossoms or honeysuckle. The tree has a symmetrical, somewhat pyramidal shape, often with different individuals of the species forming almost identical crowns. It frequently suckers and can form several vertical trunks close to ground level. The bark is gray with vertical white striations and has a ridged texture. The alternate, obovate leaves are up to 6 in (15 cm) in length and turn a bright orange-red in the fall. Although difficult to transplant, once established, F. alatamaha can live a century or more.

The seed capsules require 12–14 months to mature. Unlike almost all angiosperms, Franklinia alatamaha exhibits zygotic dormancy. It pollinates in late summer or early autumn, is then dormant over winter, and only sets fruit during the subsequent summer. Female gametophytes are mature prior to pollination, with double fertilization occurring soon after pollination. The zygote becomes dormant immediately after fertilization with delay of development until the following summer. Initial development of endosperm occurs for up to 3 months after fertilization but comes to a standstill at winter's onset. With onset of the following summer, embryogenesis begins and endosperm development restarts. This overwinter zygotic dormancy is extremely rare among temperate angiosperms.[7] When ripe the pentavalved spherical capsules split above and below in a unique manner. Anecdotal evidence suggests viable seed production is enhanced where two or more plants are present in close proximity.

History

Philadelphia botanists John and William Bartram first observed the tree growing along the Altamaha River near Fort Barrington in the British colony of Georgia in October 1765. John Bartram recorded "severall very curious shrubs" in his journal entry for October 1, 1765. William Bartram returned several times to the same location on the Altamaha during a collecting trip to the American South, funded by Dr. John Fothergill of London. William Bartram collected F. alatamaha seeds during this extended trip to the South from 1773 through 1776, a journey described in his book Bartram's Travels published in Philadelphia in 1791. William Bartram brought seed back to Philadelphia in 1777 at which time William reported to his father that he had relocated the plant, but this time had been able to retrieve its seeds although it was not until after John's death (1777) that he was able to achieve flowering plants (1781). After several years of study, William Bartram assigned the “rare and elegant flowering shrub” to a new genus Franklinia, named in honor of his father's great friend Benjamin Franklin. The new plant name, Franklinia alatamaha, was first published by a Bartram cousin, Humphry Marshall, in 1785 in his catalogue of North American trees and shrubs entitled Arbustrum Americanum. (Marshall 1785: 48–50; Fry 2001).

William Bartram was the first to report the extremely limited distribution of Franklinia. "We never saw it grow in any other place, nor have I ever since seen it growing wild, in all my travels, from Pennsylvania to Point Coupe, on the banks of the Mississippi, which must be allowed a very singular and unaccountable circumstance; at this place there are two or 3 acres (12,000 m2) of ground where it grows plentifully." (W. Bartram 1791: 468).

The tree was last verified in the wild in 1803 by the English plant collector John Lyon, (although there are hints it may have been present into at least the 1840s.).[8] The cause of its extinction in the wild is not known, but has been attributed to a number of causes including fire, flood, overcollection by plant collectors, and fungal disease introduced with the cultivation of cotton plants.[9]

All the Franklin trees known to exist today are descended from seed collected by William Bartram and propagated at Bartram's Garden in Philadelphia. It has now been cultivated in excess of 1000 sites worldwide including botanical gardens, private homes, parks, and cemeteries.[10][11] To mark the 300th anniversary of John Bartram's birth in 1998, Bartram's Garden launched a project to locate as many Franklinia trees as possible.[11]

Cultivation

The Franklin tree has a reputation among gardeners for being difficult to cultivate, especially in urban environments. It prefers sandy, high-acid soil, and does not tolerate compacted clay soil, excessive moisture, or any disturbance to its roots. The Franklin tree has no known pests, but it is subject to a root-rot disease and does not endure drought well.[12]

Gallery

- Leaves

- Leaf closeup

- Trunk bark

Fall leaves

Fall leaves Fruit capsule

Fruit capsule

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Franklinia alatamaha. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Franklinia alatamaha |

- Rivers, M.C. (2015). "Franklinia alatamaha". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T30408A62077322. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T30408A62077322.en.

- Franklinia alatamaha was originally described and published in Arbustrum Americanum: The American Grove, or, an Alphabetical Catalogue of Forest Trees and Shrubs, Natives of the American United States, Arranged according to the Linnaean System. Philadelphia. 49 (-50). 1785. "Franklinia alatamaha". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- Barstow, Megan (2018). "Two of the world's tea species extinct in the wild according to new report". phys.org. Retrieved 2020-08-07.

- Tsou, Chih-Hua. 1998. "Early Floral Development of Camellioideae (Theaceae)," American Journal of Botany, 85(11), p. 1531-1547.

- Orton, Elwin R., Jr. 1977. "Successful Hybridization of Gordonia lasianthus (L.) Ellis x Franklinia alatamaha Marshall," American Association of Botanical Gardens and Arboreta, vol. 11, no. 4 (October), p. 81-84.

- Ranney, Thomas G. and Thomas A. Eaker, Paul R. Frantz, Clifford R. Parks. 2003 "xSchimlinia floridbunda (Theaceae): A New Intergeneric Hybrid between Franklinia alatamaha and Schima argentea," HortScience, vol. 38(6), October, p. 1198-1200.

- Kristel M. Schoonderwoerd, William E. Friedman, Zygotic dormancy underlies prolonged seed development in Franklinia alatamaha (Theaceae): a most unusual case of reproductive phenology in angiosperms, Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, Volume 181, Issue 1, May 2016, Pages 70–83, https://doi.org/10.1111/boj.12409

- Bozeman, John R. and George A. Rogers. 1986. “‘This very curious tree’: Despite years of searching and research the enigma of Franklinia alatamaha endures,” Tipularia, (November), p. 9-15.

- Dirr, Michael A. 1998. Manual of Woody Landscape Plants: Their Identification, Ornamental Characteristics, Culture, Propagation and Uses. Stipes Publishing L.L.C.: Champaign, IL.

- Bartram's Garden (Philadelphia, Pa., USA), "The Franklinia Story," http://www.bartramsgarden.org/franklinia/index.html Archived 2007-08-21 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 1 July 2007.

- Meier, Allison C. (2018-04-27). "America's Mysterious Lost Tree". JSTOR Daily. Retrieved 2020-08-07.

- U.S. Forest Service, "Franklinia Alatamaha, Franklin-Tree," Fact Sheet ST-260, November 1993.

- Bartram, William. 1791. Travels Through North & South Carolina, Georgia, East & West Florida,…. James & Johnson: Philadelphia.

- Fry, Joel T. 2000. “Franklinia alatamaha, A History of that ‘Very Curious’ Shrub, Part 1: Discovery and Naming of the Franklinia”, Bartram Broadside, (Spring), p. 1-24.

- Marshall, Humphry. 1785. Arbustrum Americanum. The American Grove, or an Alphabetical Catalogue of Forest Trees and Shrubs, Natives of the American United States, Arranged According to the Linnaean System…, Joseph Cruikshank: Philadelphia.

External links

- USDA Plants Profile for Franklinia alatamaha (Franklin tree)

- Bartram's Garden: Franklinia

- Treetrail.net: Franklinia Article and Photos

- entry in New Georgia Encyclopedia

- Del Tredici, Peter. "Against All Odds: Growing Franklinia in Boston." Arnoldia 63 (4) (2005).

- Wood, Carroll E.. "Some Cultivated Relatives of the Camellia." Arnoldia 17 (1-2) (1957).