Fort Stevens Ridge

Fort Stevens Ridge is a neighborhood in Northwest Washington, D.C. built during the 1920s. The neighborhood comprises about 50 acres (0.20 km2)[1][2] and is very roughly bounded by Peabody Street, Fifth Street, Underwood Street, and Ninth Street.[3] As of the 2010 census, the neighborhood had 2,597 residents.[4] It was named for nearby Fort Stevens,[1] a Civil War-era fort used to defend the nation's capital from invasion by Confederate soldiers.

Fort Stevens Ridge | |

|---|---|

Neighborhood of Washington, D.C. | |

| Country | United States |

| District | Washington, D.C. |

| Ward | Ward 4 |

| Government | |

| • Councilmember | Brandon Todd |

History

Early history

A street map from 1894 shows the land that later became Fort Stevens Ridge as being owned by Orlanda Gray.[5] The land was part of large stretch of undeveloped land, with only a small amount of development in nearby Brightwood at the intersection of Brightwood Avenue (later renamed Georgia Avenue) and Shepherd Road (near modern-day Missouri Avenue).[5]

In 1903, Gray still owned the land, but development had increased.[6] North Brightwood had been built in four square blocks surrounded by Brightwood Avenue, Nicholson Street, Eighth Street, and Peabody Street.[6] Peters Mill Seat had also been built in two square blocks surrounded by Brightwood Avenue, Madison Street, Eight Street, and Nicholson Street.[6]

By 1919, the land was owned by the Fort Stevens Tract Company Inc.[7] Many of the surrounding streets had been renamed; Madison, Nicholson, Oglethorpe, and Peabody streets had been renamed Quackenbos, Rittenhouse, Sheridan, and Tuckerman streets, respectively.[7] The newly renamed Rittenhouse Street had been extended eastward and now connected the developments of North Brightwood and Manor Park.[7]

Development

In 1920, real estate developer Harry Wardman and his business partner Thomas P. Bones bought the forested plot of land with the intention of building moderately priced housing, which was scarce in Washington following World War I. Wardman had already successfully built houses in other Washington neighborhoods such as Bloomingdale, Columbia Heights, and Mount Pleasant.

The area was favorable for several reasons. It was within walking distance to schools, shopping, churches, and parks. It was also convenient to public transportation, namely the Brightwood Railway, which traveled downtown along Georgia Avenue.

The land was originally zoned for single-family and semi-detached housing.[8] Wardman initially sought to rezone the land for what he called community houses, which were rows of three, five, or nine attached houses.[8][9] Residents of the nearby Manor Park, Brightwood, and Takoma neighborhoods objected to Wardman's plans to increase the density of the area, saying it would change the suburban feel of the neighborhood.[9][10] The zoning commission denied Warman's request to rezone the area,[11] and Wardman ended up to building semi-detached houses after all.

Construction began in July 1924,[12] and the first homes were completed by November 1924.[13] Because Rittenhouse Street was a major thoroughfare running through the middle of the land, Wardman built the first houses on Rittenhouse Street.[14] As the first houses neared completion, work began on houses on 7th Street and Roxboro Place.[15] Each semi-detached house was built two stories high with six finished rooms, an unfinished basement, a front and back porch, [16] and a small yard in the front, side, and back.[17]

As Wardman developed more of the land, American culture changed. Increasingly, families were buying cars and desired garages. Wardman built street-level garages under the side porches of some of last houses built, in the 600 block of Somerset Street. The resurfacing of Georgia Avenue during the beginning of work on the development made the development more attractive to residents with cars,[14] and the nearby Georgia Avenue and Takoma Park trolley lines made it attractive to residents without cars.[16]

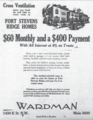

Wardman placed advertisements for the housing in local newspapers such as the Washington Post and Evening Star.[18] The advertisements centered on the houses' modern amenities as well as their low prices,[16] which were possible due to their mass production and Wardman's ownership of a planing mill and a woodworking company.[3] Wardman's advertisements highlighted the "select environment of a restricted community".[16] The first construction phases of houses were offered for sale from $6,750 to $7,150 each,[16] with payment plans available asking a $400 down payment and $65 each month thereafter.[19] The first model houses were located at 605 Rittenhouse Street[13] and 608 Roxboro Place.[20]

Advertisements

Advertisement for Fort Stevens Ridge in The Washington Post, May 17, 1925.

Advertisement for Fort Stevens Ridge in The Washington Post, May 17, 1925. Advertisement for Fort Stevens Ridge in The Washington Evening Star, August 1, 1925.

Advertisement for Fort Stevens Ridge in The Washington Evening Star, August 1, 1925. Advertisement for Fort Stevens Ridge in The Washington Evening Star, July 30, 1926.

Advertisement for Fort Stevens Ridge in The Washington Evening Star, July 30, 1926. Advertisement for Fort Stevens Ridge in The Washington Evening Star, December 4, 1926.

Advertisement for Fort Stevens Ridge in The Washington Evening Star, December 4, 1926. Advertisement for Fort Stevens Ridge in The Washington Evening Star, March 8, 1927.

Advertisement for Fort Stevens Ridge in The Washington Evening Star, March 8, 1927.

References

- "Fort Stevens Ridge Dwellings Sought". The Washington Post. May 17, 1925. p. 5. ProQuest 149610386.

- "Paving Georgia Avenue: 1,000 Houses to Be Built in New Section on Fort Stevens Ridge" (PDF). The Evening Star. August 30, 1924. p. 13.

- "Wardman Sells Homes on Ft. Stevens Ridge". The Washington Post. September 12, 1926. p. 3. ProQuest 149669583.

- District of Columbia - New Ward 4 2010 Total Population by Census Block by Ward, ANC and SMD Boundaries Archived 2012-10-06 at the Wayback Machine. Office of Planning. Government of the District of Columbia. July 1, 2011.

- Baist's Real Estate Atlas Surveys of Washington, District of Columbia, Volume 3, Plate 20 (Map). Baist, George William. 1894.

- Baist's Real Estate Atlas Surveys of Washington, District of Columbia, Volume 3, Plate 24 (Map). Baist, George William. 1903.

- Baist's Real Estate Atlas Surveys of Washington, District of Columbia, Volume 3, Plate 20 (Map). Baist, George William. 1919.

- "Zone Commission to Hear Proposed Amendment Today". The Washington Post. May 20, 1926. p. 8. ProQuest 149694365.

- "Residents Oppose Zone Area Change At Public Hearing". The Washington Post. May 21, 1926. p. 22. ProQuest 149600926.

- "Manor Park Citizens Opposed to Rezoning". The Washington Post. April 14, 1925. p. 10. ProQuest 149592118.

- "Row House Ban Unheld For Manor Park Tract". The Washington Post. October 21, 1926. p. 22. ProQuest 149680303.

- "Wardman to Build 1,000 Dwellings on Ft. Stevens Ridge". The Washington Post. July 27, 1924. p. 3. ProQuest 149492344.

- "Fort Stevens Ridge Exhibit Home Opened". The Washington Post. November 9, 1924. p. 20. ProQuest 149496042.

- "Fort Stevens Homes Nearing Completion". The Washington Post. August 31, 1924. p. 3. ProQuest 149486855.

- "Fort Stevens Ridge Homes Near Completion". The Washington Post. October 5, 1924. p. 2. ProQuest 149359908.

- Wardman Construction Company (May 17, 1925). "Fort Stevens Ridge". The Washington Post. p. 3. ProQuest 149602992.

- Wardman Construction Company (November 1, 1925). "24 New Dwellings Await Your Inspection". The Washington Post. p. 4. ProQuest 149518677.

- "Fort Stevens Ridge" (PDF). The Evening Star. May 16, 1925. p. 19.

- Wardman Construction Company (March 7, 1926). "What You Desired Yesterday You Can Afford to Buy Today". The Washington Post. p. 1. ProQuest 149702728.

- Wardman Construction Company (June 9, 1925). "New Brick Homes Semi-detached". The Washington Post. p. 19. ProQuest 149573258.

Further reading

- "Celebrating a Century of Wardman Row House Neighborhoods". Exhibition by the Historical Society of Washington, D.C. Carnegie Library Building, Washington, D.C., February 2007. Archived from the original on February 3, 2007.

- Fleishman, Sandra. "Wardman's World: Developer's Rowhouses Defined the District in the Early 20th Century and Are Still Prized Today", The Washington Post, October 15, 2005.