Fort Concho

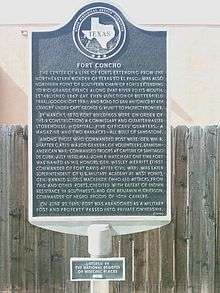

Fort Concho is a former United States Army installation located in San Angelo, Texas. It was established in November 1867 at the confluence of the Concho Rivers and on the Butterfield Overland Mail Route and Goodnight–Loving Trail. At its height during the American Indian Wars, Fort Concho consisted of 40 buildings on 40 acres (16 ha) of land leased by the US Army. The fort was abandoned in June 1889 and fell into civilian hands. Over the next twenty years, its buildings were used as residences or recycled for their material in the nearby town of San Angelo. Beginning in the late 1920s, a serious effort has been made to preserve and restore Fort Concho by its eponymous museum organization, founded in 1929. The property has been owned and operated by the city of San Angelo since 1935. It was named a National Historic Landmark on 4 July 1961. Fort Concho is one of the best-preserved examples of the military installations built by the US Army in the state of Texas.

Fort Concho Historic District | |

Texas State Antiquities Landmark | |

Headquarters building, September 2017 | |

Fort Concho, San Angelo, Texas Location in Texas and the United States  Fort Concho, San Angelo, Texas Fort Concho, San Angelo, Texas (the United States) | |

| Location | 630 S. Oakes Street San Angelo, Texas, United States |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 31°27′10″N 100°25′45″W |

| Area | 42 acres (17 ha) |

| Built by | United States Army |

| Website | fortconcho |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000823 |

| TSAL No. | 8200000596 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966[1] |

| Designated NHLD | July 4, 1961 |

| Designated TSAL | January 1, 1986 |

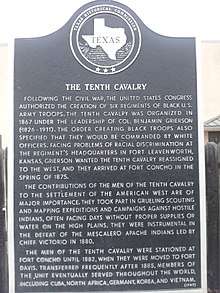

Over its 22-year career as a US Army base, Fort Concho housed elements of fifteen US Cavalry and Infantry regiments, most prominently the "Buffalo Soldiers" of the 9th and 10th Cavalry and 24th and 25th Infantry regiments. From its establishment in 1867 until 1875, Fort Concho was the principal base of the 4th Cavalry and then of the 10th Cavalry from 1875 to 1882. From 1878 to 1881, the fort was the headquarters of the short-lived District of the Pecos, and troops stationed at Fort Concho participated in Ranald S. Mackenzie's 1872 summer campaign, the Red River War in 1874, and the Victorio Campaign of 1879–1880.

Operation by the US military

Conflict in the Texas region between Native American tribes and white settlers spanned over 300 years, beginning in the early 16th century with Spanish missionaries and soldiers and ending with the cessation of organized resistance to the government of the United States of America in the 1870s.[2] In the area that is now Concho Valley, the Jumano people established a village on the North Concho River sometime before 1534, when Cabeza de Vaca stayed there. Franciscan friars established a mission there between 1629 to 1632 and were joined in the 1650s by traders from Santa Fe. In the 1690s, the Jumanos were driven out of the region by the Apache, who themselves were pushed southwest by the Comanche in the mid-18th century.[3] With America's victory over Mexico in the Mexican–American War in the 1830s and the 1849 discovery of gold in California, American colonists began crossing Comancheria. The native Comanche, Kiowa, and Kickapoo peoples fiercely resisted them. To protect its citizens, the United States Army's Department of Texas surveyed the frontier by 1851 and built a string of forts along principal routes of travel.[4]

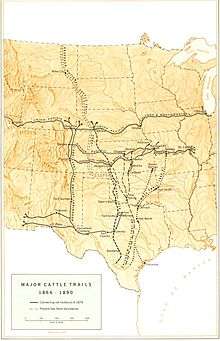

In March 1852, American troops established a camp on the North Concho that was abandoned with the establishment, in October 1852, of Fort Chadbourne on a tributary of the nearby Colorado River. Patrols launched from the fort still covered the Concho valley and the Butterfield Overland Mail route, established in 1858.[5] This phase of frontier history ended three years later with the beginning of the American Civil War.[2] Fort Chadbourne, like other Texas forts, was abandoned by Federal troops until the surrender of the Confederacy.[5] During this time, the frontier receded to the east and the Comanche were emboldened into increased raiding.[6] With the establishment in 1866 of the Goodnight-Loving Trail, which followed the Middle Concho River west, there came an increased need to protect cattlemen and settlers traveling around the Concho valley. To this end, the 4th Cavalry, commanded by Major John P. Hatch, reoccupied Fort Chadbourne in May 1867. This was soon followed up by plans to establish an outpost on the Concho, where US troops and citizens would have a reliable and inexhaustible supply of water.[5]

In the summer of 1867, Hatch ordered Lieutenant Peter M. Boehm to establish a camp on the Middle Concho, 50 miles (80 km) south of Fort Chadbourne. Captain Michael J. Kelly and 50 troops established this camp that summer, but on the North Concho, and remained there for the duration of the summer. A committee of officers including Hatch surveyed the North and Middle Concho rivers in September 1867 and chose a plateau at the junction of the three Conchos for its grazing grounds, the abundance of nearby limestone, and inexhaustible supply of fresh water. On 28 November 1867, the 4th Cavalry's H Company departed from Fort Chadbourne for the site to establish the outpost. H Company's commander, Captain George G. Huntt, named the site "Camp Hatch", but changed it to "Camp Kelly" in January 1868 at Hatch's request to honor Kelly, who had died of typhoid fever on 13 August 1867. Fort Concho, then under construction north of Camp Kelly, received its name in March 1868 from Edward M. Stanton, Secretary of War for the United States.[7] The land Fort Concho was built on was not bought by the US government, but leased.[8]

Construction

Construction of Fort Concho was assigned on 10 December 1867 to Captain David W. Porter, assistant quartermaster of the Department of Texas. He brought in civilian stonemasons and carpenters to construct first temporary storehouses and then a permanent commissary in January 1868. Porter, also responsible for constructing Forts Griffin and Richardson, was replaced in March by Major George C. Cram, who built a temporary guardhouse. Construction was slow, as direction had been poor under Cram and his predecessor, who was rarely at Fort Concho. By Spring 1868, the only permanent building on-site was a sutler's store, constructed from pickets and pecan rafters. The soldiers lived in tents heated by fireplaces and sometimes stoves or in timber huts. As at other forts, they also built temporary timber frame or picket buildings lined with canvas insulation. Over 1868, Cram began a dispute with Major Ben Ficklin, the regional mail line superintendent, that resulted in Cram's having Ficklin arrested. The Postmaster General soon became involved and by August Cram was reassigned out of the Concho valley. He was replaced with Major George A. Gordon, who handed Fort Concho's construction to Captain Joseph Rendlebrock, the 4th Cavalry's quartermaster.[9]

By the end of 1868, Rendlebrock had completed the commissary, quartermaster's storehouse, and a wing of the hospital. Like Porter, Rendlebrock employed civilian masons and carpenters, mostly German immigrants from Fredericksburg. The first permanent military structures on the fort grounds, five of the officer's residences and the first regimental barracks, were completed by August 1869. As officers began moving into the completed buildings, the non-commissioned officers, baker, drum major, and chief musician continued to live in temporary housing. In October 1869, a timber frame building was put up for the post adjutant and quartermaster on the parade ground. Over 1870, two more officer's residences and another barracks were built, as well as a permanent guardhouse and stables. Hatch pushed for the completion of the fort through 1870–71, directing the building of a quartermaster's corral, a wagon shed, and a failed attempt at producing adobe bricks that earned him the moniker "Dobe". Construction was again slowed in February 1872 with the discharging of most of the civilian workforce following budget cuts to the US War Department, but by the end of the year Fort Concho consisted of four barracks, eight officers' residences, the hospital, a magazine, stone guardhouse, bakery, several storehouses, workshops, and stables.[10]

In 1875, the parade ground was cleared and a flagstaff placed in its center. In the process, the adjutant's office was moved to the headquarters building. It was replaced in short order with a stone command structure, the Headquarters building, built in 1876. Another officers' residence was built in 1877, as were the foundations for another that went unfinished for lack of funding. This building was completed in February 1879 as the schoolhouse and chapel. It was the final permanent structure completed at Fort Concho.[11] By 1879, the fort was an eight-company installation of entirely limestone-built structures with a parade ground measuring 1,000 feet (300 m) long by 500 feet (150 m) wide.[8] Construction had cost the US Army 1 million dollars by May 1877.[12]

Base of the 4th Cavalry

The first act undertaken by the 4th Cavalry when establishing Fort Concho was to build a wagon road to the San Saba River to secure a supply route from Fort Mason. When not on construction details, the garrison patrolled, scouted, and escorted wagon trains on the Butterfield Overland Trail and San Antonio–El Paso Road and cattle herds. Encounters with hostile Native Americans were rare.[13]

On 25 February 1871, Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie took command of the 4th Cavalry. He moved the regimental headquarters to Fort Richardson a month later,[14] but kept a few companies at Fort Concho.[15] In May 1871, the 4th Cavalry contingent left at Fort Concho participated in a campaign against the Kiowa in retaliation for the Warren Wagon Train raid with troops from Forts Griffin and Sill. Six troops of 4th Cavalry's I Company, commanded by Captain Napoleon B. McLaughlen, joined the rest of the regiment at the Little Wichita River in pursuit of the Kiowa but turned back for Fort Concho in September after the raiders escaped. Comanche and Kiowa raids increased in number over early 1873, prompting a number of expeditions that rarely saw Native Americans. A notable exception was a patrol carried out by Sergeant William Wilson from 26 to 29 March 1872. On 28 March, his patrol fought a group of Comancheros, half-Native and Hispanic traders, and captured one of their number. The captured man, Apalonio Ortiz, revealed that there was water in the Staked Plains and the location of a large Comanche settlement and base of trade for the Comancheros at Mushaway Peak. Hatch,[16] in charge of Fort Concho while Mackenzie was in the field,[17] reported Wilson's findings to Mackenzie and to the Departments of Texas and New Mexico. McLaughlen set out again with two companies of the 4th Cavalry and one of the 11th Infantry to verify Ortiz's information and confirmed it. His expedition, which had also mapped some of the Staked Plains, returned on 13 May.[18]

After Mackenzie and Hatch met with General Christopher C. Augur, Commander of the Department of Texas, Mackenzie and McLaughlen, commanding Companies D and I, departed from their respective installations on 17 June. Over the following months, the 4th Cavalry explored the South Plains and fought the Comanche at the Battle of the North Fork of the Red River on 29 September. As a result of the battle, the 4th Cavalry captured 124 women and children and most of the horses of the involved Comanche warriors. The following night, the Comanche stole back some of their horses and escaped, but left their women and children as prisoners. Companies D and I returned to Fort Concho on 21 October with 116 of the noncombatants, who were interned in the quartermaster's corral. They remained in captivity at the fort until the Department of Texas ordered the release of the Comanche hostages on 14 April 1873. They departed Fort Concho on 24 May under escort from the 11th Infantry and arrived safely at Fort Sill on 10 June.[19]

In March 1873, Mackenzie moved the 4th Cavalry's command from Fort Concho to Fort Clark. That year, he embarked on another campaign, this time against the Kickapoo based across the Rio Grande in Mexico. Company I and McLaughlen again joined Mackenzie in the field for his attack into Coahuila, Mexico on 18 May 1873. On 27 June 1874, more than 200 Comanche warriors attacked a group of buffalo hunters camped at Adobe Walls, beginning the Red River War. In response, Augur ordered Mackenzie and the 4th Cavalry back to Fort Concho in July. When the US Army asked for permission to follow the Comanche and their allies onto reservations, the Secretary of War granted it. By August,[20] General Philip H. Sheridan, commanding the Military Division of the Missouri, ordered five expeditionary forces of more than 3,000 soldiers into the South Plains.[15] The southern force, under Mackenzie, left Fort Concho on 23 August 1874 with eight companies of the 4th Cavalry, four of the 10th Infantry, and one from the 11th Infantry. Over the course of the war, Mackenzie chased the Comanche until he found their base of operations in the Palo Duro Canyon and destroyed it on 28 September. His force continued to patrol the area over the winter, preventing the Comanche from rebuilding their supplies and cementing the American victory in the Red River War. Left no other option, the Comanche returned to their reservation.[21]

Base of the 10th Cavalry

In early 1875, the 4th Cavalry was entirely transferred out of Fort Concho to Fort Sill to watch over the Comanche and were replaced by Fort Sill's previous garrison, the 10th Cavalry, commanded by Colonel Benjamin Grierson. Grierson and his "Buffalo Soldiers" arrived at Fort Concho on 17 April 1875 and established the regimental headquarters there. The 10th Cavalry took up the duties the 4th Cavalry previously held: patrolling the frontier, escorting wagons and settlers, and mounting expeditions. One of these was Captain Nicholas M. Nolan's disastrous expedition in July 1877.[22] Four men of the 10th Cavalry's Company A died on the trip by the time it returned to Fort Concho on 31 July.[23][24]

Apache raids from the Mescalero and San Carlos reservations in the mid-1870s prompted the creation of the District of the Pecos in January 1878. This was placed under Grierson's command and based at Fort Concho. Over the next two years, Grierson established outposts like Grierson Spring across West Texas. In October 1879, Grierson received word that a war party of Ojo Caliente and Mescalero Apache under Chief Victorio entered the Trans-Pecos. He left Fort Concho on 23 March 1880 at the head of five companies of the 10th Cavalry and some of the 25th Infantry to disarm the Mescaleros of the Fort Stanton reservation. Grierson's soldiers fought with Apache raiders over early April, then reached Fort Stanton on 12 April. The disarmament was delayed until 16 April because of rains, and resulted in failure when the Mescalero Apache escaped with most of their arms. Grierson returned to Fort Concho on 16 May but left the 10th Cavalry's M Company at the head of the North Concho in case the Apache appeared in the area.[25]

On 17 June 1880, Nolan and a battalion of the 10th Cavalry at Fort Sill returned to Fort Concho by Grierson's order. Ten days later, Grierson sent Nolan to patrol the Guadalupe Mountains and himself set out from Fort Concho on 10 July.[26] Grierson harried Victorio over the summer until Victorio was defeated at Rattlesnake Springs and driven into Mexico. There, Victorio's band was destroyed on 15 October 1880 by Mexican soldiers under the command of Colonel Joaquín Terrazas.[27] The 10th Cavalry left Fort Concho for the last time in July 1882 for Fort Davis, farther to the west.[28]

Post-Texas Indian Wars and deactivation

On 27 January 1881, the Texas Rangers fought and defeated what was left of Victorio's band in the final battle of the American Indian Wars fought in Texas. The District of the Pecos was disbanded the following month. In August 1882, the 10th Cavalry was replaced at Fort Concho by the 16th Infantry, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Alfred L. Hough. Ten days before Hough and the regimental headquarters arrived at the fort, a massive flood of the Concho wiped Ben Ficklin off the map and badly damaged San Angelo. As a result, the 16th Infantry spent its first week on-site rendering humanitarian aid. After recovering, San Angelo began to prosper while Fort Concho declined from poor maintenance.[29] From 1882 until the fort's final closure, it served primarily as a base for troops awaiting transfer elsewhere in Texas.[8] When Fort McKavett was abandoned by the US Army in June 1883, its garrison moved to Fort Concho.[30]

By the mid-1880s, the ranches that now enclosed the surrounding plains with barbed wire fencing reduced the soldiers, barred by law from cutting the wire, to patrolling roads. Many of the frontier forts, such as Forts Davis and Griffin, had either been abandoned or were awaiting deactivation. After the 16th Infantry left Fort Concho for Fort Bliss in February 1887, it was believed locally that Fort Concho would also be abandoned. In early 1888, the 8th Cavalry gathered at Fort Concho from around Texas and then left for Fort Meade, in South Dakota, in June. With their departure, only the 19th Infantry's K Company were garrisoned at Fort Concho. Later that same year, on 17 September, the Santa Fe Railroad reached San Angelo. Interested locals appealed in vain to the Federal Government to make Fort Concho a permanent installation. On 20 June 1889, the men of K Company lowered the flag over the fort for the final time and left the next morning.[31]

Relationship with San Angelo, Texas

.jpg)

Bartholomew J. DeWitt borrowed $1500 from Marcus Koenigheim, a San Antonio-based investor and used it to buy a half-section of land on the opposite side of the Concho River of Fort Concho in 1870. He divided the area into plots to build a town, which he named Saint Angela (changed to San Angelo in 1881) after his wife, Carolina Angela de la Garza. The township was not a profitable venture. When Ben Ficklin was made the seat for Tom Green County instead of San Angelo, Koenigheim asked for payment of the balance and interest of DeWitt's loan in full. When he was unable to pay, Koenigheim sued him in 1875 and was awarded the 372 acres (151 ha) of land that constituted the town. By then, San Angelo was a collection of saloons and brothels and had a reputation befitting that.[32][33]

Relations between the town and Fort Concho's garrison, who called San Angelo "the town over the river", were tentative. The enlisted men often spent and money in the town, but its inhabitants treated the garrison's black soldiers with racist disdain and violence. When one of the Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th Cavalry was murdered on 31 January 1881, an entire company of the 16th Infantry and the slain man's comrades arrested the sheriff on 2 February and demanded the murderer. He was not given up, but the soldiers returned to the fort without incident. Two days later, and acting on rumors that the murderer had been released, the soldiers returned and attacked the Nimitz Hotel, where he was rumored to be staying.[34] The Texas Rangers arrived to help calm the situation and did this by issuing threats to attack the fort and to shoot any soldier that crossed the Concho River in a ten-day period.[35] Tension existed between the civilians and Fort Concho until after the 10th Cavalry left in 1882 and was replaced by the 16th Infantry. The aid rendered to locals by the fort's garrison, especially the 16th Infantry, following the flood of 1888 and fires in the vicinity eventually evaporated the lingering animosity.[36]

Fort Concho was crucial to San Angelo's early growth. The presence of its garrison attracted traders and settlers and allowed diversification of the town's economy.[33] Some of the sutlers that supplied Fort Concho's troops were William S. Veck, one of the organizers of Tom Green County and owner of San Angelo's first bank, and James L. Millspaugh, another county commissioner who helped bring the railroad to San Angelo.[37] When the fort was abandoned, the local economy suffered enough to cause the closing of Koenigheim's business in San Angelo.[38] Fort Concho's chaplains were some of the first preachers and educators in the town. The medical staff, chiefly surgeon William Notson, treated not just the garrison but also civilian townsfolk and ranchers. One of Notson's civilian assistants, Samuel L.S. Smith, became San Angelo's first physician and in 1910 helped establish its first civilian hospital.[39]

Preservation

In the last years of the 19th century, the post buildings became residences for the people of San Angelo.[40] Enlisted Barracks 3 and 4 fell into ruin and were replaced with a series of residences while the officer's residences were preserved as private homes. However, despite a state of general disrepair, effort was still made by interested locals to preserve Fort Concho.[41] When C.A. Broome formed the Fort Concho Realty Company in 1905 to sell off his land in San Angelo and at Fort Concho, he implored the city to buy the fort for $15,000 without success. The eastern third of the fort grounds, which had remained preserved, was given to the city by the Santa Fe Railroad Company in 1913. A decade later, the local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution tried and failed to raise funds to preserve the fort. Instead, a stone and bronze plaque was placed that is still present at the fort.[41][42]

In 1928, Ginevra Wood Carson founded the West Texas Museum in a room of the Tom Green County Courthouse. The next year, she raised funds for and made a purchase of the Headquarters for $6000. Over 1930, she moved the museum into the building and renamed it the Fort Concho Museum.[8][42] The city of San Angelo assumed partial administrative responsibility for the museum in 1935, then fully annexed the museum in 1955.[40][41] Fort Concho was named a National Historic Landmark on 4 July 1961,[43] bringing federal resources and trained professionals to Fort Concho.[41] A three-phase plan was presented to the National Park Service in 1967 for the acquisition, preservation, and restoration of the fort site and the funding required.[42] Restorations followed in the 1970s,[41] culminating in a 1980 plan by an Austin-based architectural firm. By the end of the 1980s, the Fort Concho Museum complex consisted of sixteen original buildings, six reconstructed buildings, and a stabilized ruin.[42]

Recent history

On 3 April 2008, following a call from an alleged victim of abuse by members of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, a polygamist Mormon sect, Texas authorities raided the YFZ Ranch. The authorities began removing children from the ranch the next day, and relocated them to Fort Concho on 5 April. The State of Texas was granted conservatorship over the children on 7 April, and seven days later moved all women accompanying children older than five years to the Foster Communications Coliseum, also in San Angelo.[44] On 2 June, the Texas Supreme Court ruled that the seizure of the children was unlawful, and the children were released from state custody.[45]

Late in 2017, the Fort Concho Museum announced its plans for 2018, funded by the city of San Angelo and private donors. These included the expansion of the visitor's center into the entirety of Barracks 1 and 2, and the reconstruction of Barracks 3 and 4 as well as their mess halls.[46]

Grounds and architecture

Fort Concho was constructed from limestone quarried south of the fort, which supplied lime for the mortar mixture also used in its construction. Most of the wood used in the fort's construction was shipped from the Gulf Coast, as the native pecan and mesquite trees were unsuitable for construction.[47]

The landmark today includes most of the original fort and 23 main structures, mostly original or restored, but some reconstructions. These structures include a headquarters, officers' quarters, soldiers' barracks, and the post hospital. Regular and changing exhibits in the fields of military history, the heritage of San Angelo and West Texas in general, and the daily life of a soldier and an officer are on display.[48] The Fort Concho Museum has over 35,000 items related to the histories of Fort Concho and San Angelo in its collection.[42]

Barracks Row

The enlisted men's barracks were some of the first buildings erected at Fort Concho, from 1869 to 1872. Civilian laborers provided skilled labor such as carpentry while soldiers performed the construction work. Barracks 1 and 2 were built in 1869 and 1870, respectively, and each contained two cavalry companies. Both structures are unique in having sally ports in the middle of the structures to allow the soldiers to lead their horses through, rather than around, the barracks to reach the stables, located behind the buildings. Barracks 1 is currently the visitor's center while Barracks 2 is a display space housing wagons and replica artillery pieces such as a Gatling gun.[49]

The other four barracks buildings were built to house infantrymen and had an attached mess hall. Barracks 3 and 4 were completed by the end of 1872 but were demolished some time after the fort was abandoned. Barracks 5 and 6 are living history spaces and are furnished to appear as they would have during Fort Concho's military career.[50]

At the end of Barracks Row was a guardhouse, built in 1870 to replace an earlier, temporary structure.[51]

Eastern row

The commissary, started in January 1868,[7] is the oldest building at Fort Concho and in the city of San Angelo.[8]

The headquarters building was built in 1876 by order of Colonel Grierson and served as the command building for the fort until its deactivation in 1889. From 1878 to 1881, the building was the headquarters for the District of the Pecos, which included Forts Davis, Stockton, and Griffin. In addition to the adjutant's office, which it replaced, the headquarters housed the court martial, and the 10th Cavalry's regimental headquarters. Another addition was a library of 292 books established by Chaplain Norman Badger in late 1873. By the end of 1875, the library had grown to 720 books. The headquarters building was used in various capacities in the twenty years after the US Army left Fort Concho.[52] In 1929, Ginevra Wood Carson purchased the building and moved the West Texas Museum into the building.[8][42] Four of the rooms on the ground floor, the court martial, orderly's room, adjutant's office, and regimental headquarters, have been remodeled to appear as they would have during the fort's military career.[53]

The post hospital was one of the earliest buildings at the fort, built from 1868 to 1870 according to the same plan of Fort Richardson's hospital. During Fort Concho's military operation, its hospital served both military and civilian patients but had few supplies and was unsanitary. After the fort's deactivation the hospital was used as a rooming house and for storage until it was destroyed by fire in 1911. The building was rebuilt in the mid-1980s with the aid of architectural and historical records. Presently, the hospital contains a museum about frontier medicine in its north ward, a library in the south ward, and general medical exhibits in the center.[54]

The residence of Oscar Ruffini, San Angelo's first civic architect, was moved to the far east side of the fort grounds on 14 May 1951.[55]

Officers' Row

The officers' quarters were built in several phases from 1869 to the mid-1870s. These buildings were assigned by rank, regardless of the size of an officer's family. In 1879, Grierson had a water pipe laid behind the Officers' Quarters leading to a pump on the parade ground for horticultural use.[56]

Officer's Quarters 1 was the residence of the fort commander from its completion in 1872, replacing Officer's Quarters 3 in that capacity. Benjamin Grierson was the commanding officer who lived there the longest, from 1875 to 1882. Grierson added the west office, kitchen, and carriage house and placed locks on every door in the building. Grierson's daughter Edith of typhoid died in the building on 9 September 1878.[57] The Fort Concho Museum purchased the building in 1964 and it served for years as the meeting place of the Tom Green County Historical Society. Officer's Quarters 1 was renovated in 1994 and became the Concho Valley Pioneer Heritage Center.[57]

Until the completion of Officer's Quarters 1 in 1872, Officer's Quarters 3 was the home of Fort Concho's commander. This building may also have been first of the officers' residences to be completed, in 1870. Because Officer's Quarters 3 had the greatest abundance of original interior fabric, it was restored to appear as it would have in the 1870s.[58]

The schoolhouse, also functioning as a chapel, was the last permanent structure to be built at Fort Concho. The structure was begun in November 1872 as another officer's residence, but only the foundation and basement of the kitchen were completed. When funding for construction was slashed, it was decided that instead a schoolhouse and chapel would be built instead for the education of the garrison's black soldiers and religious ceremonies. Both of these had been held in various places around the fort. Chaplain Badger had requested, fruitlessly, the construction of a permanent chapel and for want of such a building built a picket and sod chapel. Badger died at the fort on 3 June 1876 and was succeeded by George W. Ward, who dedicated the chapel upon its completion on 22 February 1879. After the US Army left, the building continued functioning as a schoolhouse and, at one point, a private home. The Fort Concho Museum acquired the schoolhouse in 1946 and restored it. Since 1976, it has housed a living history event to teach local elementary schoolers about life in 1880s Texas.[59]

See also

Citations

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- Alexander & Utley 2012, p. 32.

- Matthews 2005, p. 1.

- Alexander & Utley 2012, pp. 32, 35.

- Matthews 2005, p. 2.

- Alexander & Utley 2012, p. 33.

- Matthews 2005, pp. 3–4.

- Handbook of Texas Online: Fort Concho.

- Matthews 2005, pp. 3, 4, 5, 7.

- Matthews 2005, pp. 6–10.

- Matthews 2005, pp. 10–12, 51.

- Matthews 2005, p. 12.

- Matthews 2005, pp. 3, 13.

- Handbook of Texas Online: Mackenzie, Ranald Slidell.

- Handbook of Texas Online: Fourth United States Cavalry.

- Matthews 2005, pp. 13–15.

- Handbook of Texas Online: Hatch, John Porter.

- Matthews 2005, pp. 15–16.

- Matthews 2005, pp. 16–19.

- Matthews 2005, pp. 19–21.

- Matthews 2005, pp. 21–23.

- Matthews 2005, pp. 23, 24–25.

- Handbook of Texas Online: Nolan Expedition.

- Gibson 1971, p. 6.

- Matthews 2005, pp. 26–28, 29–30.

- Matthews 2005, p. 31.

- Handbook of Texas Online: Victorio.

- Matthews 2005, p. 34.

- Matthews 2005, pp. 34, 57.

- Alexander & Utley 2012, pp. 38–39.

- Matthews 2005, pp. 58—60.

- Gibson 1971, pp. 6, 15–16, 26–27.

- Handbook of Texas Online: San Angelo, TX.

- Matthews 2005, p. 43–44.

- Gibson 1971, p. 16.

- Matthews 2005, p. 57.

- Matthews 2005, p. 55–56.

- Gibson 1971, p. 27.

- Matthews 2005, pp. 48, 51, 53–55.

- Matthews 2005, p. 61.

- Bluthardt 2010.

- Handbook of Texas Online: Fort Concho National Historic Landmark.

- National Park Service: List of NHLs by State.

- Go San Angelo, 18 April 2018.

- Associated Press, 2 June 2008.

- Go San Angelo, 28 November 2017.

- Matthews 2005, p. 6.

- Texas Department of Transportation, Texas State Travel Guide, 2007, p. 112

- Matthews 2005, pp. 7, 8, 37.

- Matthews 2005, pp. 10, 37.

- Matthews 2005, p. 8.

- Matthews 2005, pp. 10–11, 48–49.

- Matthews 2005, p. 10.

- Matthews 2005, pp. 7, 53.

- Prestiano 1984, p. 7.

- Matthews 2005, pp. 7, 11.

- Matthews 2005, p. 27.

- Matthews 2005, p. 7.

- Matthews 2005, pp. 11, 48–49, 51.

References

- Books

- Alexander, Thomas E.; Utley, Dan K. (2012). Faded Glory: A Century of Forgotten Texas Military Sites, Then and Now. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-60344-699-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bluthardt, Robert (2010). "Through the Centuries at Old Fort Concho". Ranch and Rural Living.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gibson, Joe A. (1971). Old Angelo. The Minuteman Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Matthews, James T. (2005). Fort Concho. Texas State Historical Association. ISBN 0-87611-205-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Prestiano, Robert. "Oscar Ruffini: The Early Years". Fort Concho Report. 16 (Summer 1984).

- News publications

- "Polygamist parents, children begin reunions". Associated Press. NBC News. 2 June 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- McDaniel, Matthew (28 November 2017). "Fort Concho looking forward to big things in its 151st year". Go San Angelo. USA Today.

- "Timeline: Before and after the 2008 raid on the FLDS' Yearning for Zion Ranch". Go San Angelo. USA Today. 18 April 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

Online references

- "List of NHLs by State". National Park Service. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- Texas State Historical Association

- Anderson, H. Allen. "Fort Concho National Historic Landmark". Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- Daniel, Wayne; Schmidt, Carol. "Fort Concho". Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- Duke, Escal F. "San Angelo, TX". Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- Rocap, Pember W. "Hatch, John Porter". Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- Stout, Joseph A., Jr. "Victorio". Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Wallace, Ernest. "Mackenzie, Ranald Slidell". Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- Wallace, Ernest. "Fourth United States Cavalry". Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- "Nolan Expedition [1877]". Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fort Concho. |