Fort Collier

Built by Confederate Lieutenant Collier and Virginia militia with the aid of Federal prisoners, the Fort Collier redoubt guarded the north entrance of Winchester, Virginia on the east side of the Martinsburg Pike. During later Federal occupations, it was known as Battery No. 10. The fort was set on low ground, and generally offered little military advantage, except as a guard post for the pike. LtGen Jubal Early used it as part of his defensive works in the Third Battle of Winchester.

| Fort Collier | |

|---|---|

| Winchester, Virginia | |

Fortifications at Fort Collier | |

| Type | redoubt |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | Virginia |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1861 |

| In use | 1861–1865 |

| Battles/wars | Third Battle of Winchester |

Fort Collier | |

| |

| Nearest city | Winchester, Virginia |

| Area | 10 acres (4.0 ha) |

| Built | 1861 |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 06000356[1] |

| VLR No. | 034-0165 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | April 28, 2006 |

| Designated VLR | March 8, 2006[2] |

Background

The fort is located on a tract of land acquired by Benjamin Stine from Jacob Baker in 1859. Shortly afterwards the American Civil War began, and extensive defensive preparations were made in the northern Shenandoah Valley. After General Joseph E. Johnston assumed command of Confederate forces centered in Harpers Ferry he quickly decided that Harpers Ferry was indefensible, and to re-center his defensive posture based in Winchester. The Stine farmstead and homesite was located on high ground alongside the valley pike, and made a natural defensive position for the north end of town, and was chosen as the site for the fort by Confederate Engineer Lieutenant Collier and William Henry Chase.

During the war

1861

Confederate troops began construction on July 7, 1861, under the orders of a Confederate engineering officer, Lieutenant Collier, assisted by a detachment of Federal prisoners. The supervision of construction may have been under Major William H.C. Whiting, the Chief Engineer for Gen. Johnston, and the fort was occupied by the Army of the Shenandoah during the winter of 1861 into 1862, under the command of General Johnston. It then fell under the Valley District, commanded by MajGen Stonewall Jackson one of three districts under the Department of Northern Virginia. Stonewall Jackson's headquarters was located just south of the fort.

On August 21, 1861, the fort was described in the diary of Harriet H. Griffith:

I have this day visited the breastworks or fortifications on the Martinsburg Pike with Father and Johnnie. Was exceedingly interested. First work of the kind I'd ever seen. The first time I was ever so near a cannon. I looked into them. There were four cannons planted and much ammunition there. A great many men were working [and I] saw the magazines. They have several rifle ports which seem so secure. I have read of them, but have never seen them. They had several masked batteries. It seems real strong and well built. There is a high embankment of sand bags, barrels, and brush covered with dirt, part sodded over. They intend to sod it with a big ditch on the lower side. They have completely surrounded Stine's House which is now occupied by soldiers, some of whom were working there, come cooking, some washing, some on guard, and some lounging, and some sleeping ... Surely it is something to be remembered, but I hope it will never be used."

— Harriet H. Griffith, Aug 21, 1861

1862

Defensive troops occupied the fort during the Romney Expedition in early 1861, but Jackson evacuated Winchester in March 1862 as MajGen Banks invaded the town at the outset of the Valley Campaign. By May, Jackson returned to Winchester and routed all remaining Federal troops on May 25, who chose not to defend the fort during the First Battle of Winchester.

1863

During the occupation of MajGen Milroy from January to June 1863, Federal troops manned the fort, and listed it under the name of Battery No. 10, making it a part of a series of fortifications in the defensive scheme of Gen. Milroy. As the Second Corps, Army of Northern Virginia under LtGen Ewell routed Milroy on their movement to Gettysburg, they initially bombarded Milroy's command as they holed up in the various Winchester forts, damaging the Stine house on the night of June 15. Early the next morning, Milroy abandoned the fort and Winchester, fleeing north on the pike, with Fort Collier being the last fortification abandoned as his troops marched north toward Martinsburg.

1864

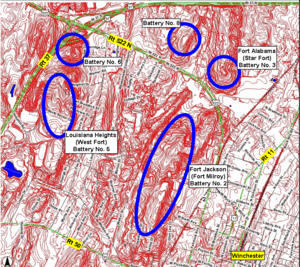

In September, 1864, the Fort and Winchester again became a base for Confederate operations during LtGen Jubal Early's Valley Campaigns of 1864. MajGen Sheridan advanced on Winchester September 17, forcing Early to make a defensive stand along the north and eastern borders of Winchester on September 19, with Fort Collier as a center piece and anchor of his defensive line, which stretched from Fort Alabama (also known as Star Fort) on the west to a long line of trenches and ramparts to the east and south of Fort Collier to the Berryville Pike. A Federal cavalry charge was made that day during the Third Battle of Winchester composed of 6,000 cavalrymen coming south from Stephenson's Depot. The assault, composed of five brigades lined across the open fields north of town, was the largest charge in the war made by cavalry against infantry.

Three regiments commanded by Colonel George S. Patton, grandfather of the World War II general, were defending the fort and locations, and Colonel Patton was killed during the course of the battle. The Confederate forces in Fort Collier and along the defensive line were overrun and the Fort was captured with no survivors, while Early's forces retreated up the Valley through Winchester, rallied for a short while at Mount Hebron Cemetery, and reconsolidated further south at Fisher's Hill near Strasburg, Virginia.[3]

Modern

The Fort Collier Civil War Center, Inc. purchased a 10-acre (40,000 m2) parcel on April 1, 2002 with the help of a Federal grant, the Civil War Preservation Trust, the County of Frederick, Virginia, and private donations. Events and activities held at the camp include the Fort Collier Kids Civil War History Camp, Civil War Haunting, Shenandoah at War Events, and the Fort Collier Bluegrass Festival.

Notes

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-06-23. Retrieved 2008-09-27.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

External links

References

- Delauter, Roger V., Jr. Winchester in the Civil War. Lynchburg, Virginia. H. E. Howard, Inc., 1992. ISBN 978-1-56190-033-6

- Mahon, Michael G., Ed. Winchester Divided: The Civil War Diaries of Julia Chase & Laura Lee. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2002. ISBN 0-8117-1394-6

- Noyalas, Jonathan A. Plagued by War: Winchester, Virginia During the Civil War. Leesburg, VA: Gauley Mount Press, 2003. ISBN 0-9628218-9-6