Forest City, Utah

Forest City is a ghost town in Utah County, Utah, United States. It is located in the valley of Dutchman Flat in the upper part of American Fork Canyon, in the Uinta National Forest. A silver mining town just over the mountain from Alta, Forest City was inhabited about 1871–1880. The town grew up around the smelter that was built to process ore from the canyon's mines. The American Fork Railroad, which was intended to serve Forest City and the smelter, stopped short of its destination due to engineering difficulties. Transportation costs rose too high for the mines to continue operating profitably. As the smelter, mines, and railroad closed down, Forest City was abandoned.

Forest City | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Scenes in American Fork Canon, 1876: 1. Mt. Aspinwall or Lone Mountain. 2. Rock Summits. 3. Picnic Grove, Deer Creek. 4. A quiet Glen. 5. Hanging Rock. 6. Rock Narrows. | |

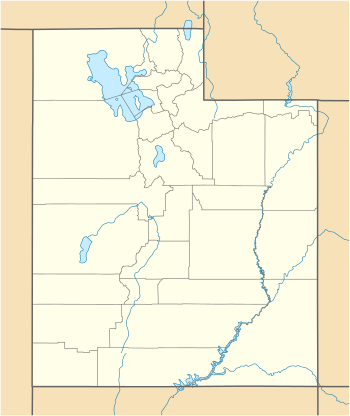

Forest City Location of Forest City in Utah  Forest City Forest City (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 40°31′40″N 111°36′10″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Utah |

| County | Utah |

| Established | 1871 |

| Abandoned | 1880 |

History

Start-up

Soon after the discovery of silver in Little Cottonwood Canyon in the late 1860s, prospectors crossed the mountain ridge to the south and staked more claims in American Fork Canyon. The largest mine, the Miller Hill Mine, developed quickly, and in 1871 was purchased for $120,000[1] by the Aspinwall Steamship Company of New York City.[2] They built a smelter at Dutchman Flat called the Sultana Smelting Works, which employed 250–300 men in 1871. It was one of the most costly smelters in Utah Territory.[3] The town that grew around the smelter was named Forest City.

The smelter's production soon outpaced the ability to transport bullion and ore out of the canyon. In April 1872 the Aspinwall Steamship Company organized the American Fork Railroad Company to address this problem. They planned to build a narrow gauge railway from the city of American Fork up the canyon to Forest City.[2] The Utah Southern Railroad, which at the time went no further south than Sandy, was scheduled that year to extend its track southward through Utah Valley, and the new railroad was to join it at American Fork.[3] Construction on the line began from American Fork in May 1872, and by August it had reached the mouth of the canyon.[4]

Decline

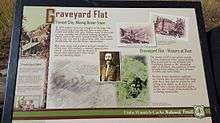

In late 1872, severe winter weather forced operations in American Fork Canyon to shut down for the season. At that time the population of Forest City was estimated at 500. The town included a sawmill, two general stores, hotels, houses,[3] and a successful saloon.[5] That winter a diphtheria epidemic swept the town, killing a number of people including 11 children. The dead were buried in a small cemetery nearby, which became known as Graveyard Flat.[6]

Population figures for Forest City are uncertain, ranging as high as 2000–3000 at the peak. There were enough children that a school was established. A dairy farm supplied the town with milk and butter. 15 kilns produced charcoal for the smelter, with another 10 down in Deer Creek.[1]

In the years 1874–1876 the American Fork Canyon mines began to peter out. The higher-grade ore bodies were being exhausted. Prospecting even further up the canyon led to the discovery of other good veins, but the country was rugged and development slow.[7] In order to cover expenses the railroad began taking tourist groups up the canyon on sightseeing trips. The Miller Hill Mine stopped producing ore by 1874, started up again briefly the next year, then shut down permanently.[3] The Sultana Smelter was dismantled in 1876, and Forest City was in serious decline.[2] The canyon's other mines were not rich enough to keep the railroad profitable. In June 1878 the American Fork Railroad became the first Utah railroad to go out of business.[3] Forest City was deserted by 1880.[1]

Remnants

Little is left of Forest City today. The foundations of the smelter and of some houses are still visible.[1] The cemetery at Graveyard Flat was preserved for years, but over time people drove snowmobiles and all-terrain vehicles over it and even tore down the picket fence surrounding it. As of 2004, only a wooden sign remained.[8] On National Public Lands Day in September 2012, Forest Service employees and volunteers from local four-wheeling clubs gathered at Graveyard Flat, built a new sturdier fence around the graveyard, and replaced the old wooden sign with two newer interpretive signs depicting the history of the town and the cemetery.

References

- Carr, Stephen L. (1986) [June 1972]. The Historical Guide to Utah Ghost Towns (3rd ed.). Salt Lake City, Utah: Western Epics. p. 51. ISBN 0-914740-30-X.

- "The American Fork Mining District". History of the Uinta National Forest: A Century of Stewardship. United States Forest Service. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- Reeder, Clarence A., Jr. "The History of Utah's Railroads, 1869–1883". UtahRails.net. Don Strack. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- Carr, Stephen L.; Edwards, Robert W. (March 1990). Utah Ghost Rails. Salt Lake City: Western Epics. pp. 116–119. ISBN 0-914740-34-2.

- Shelley, George F. (1993) [1945]. Early History of American Fork: With Some History of a Later Day (2nd ed.). American Fork City. p. 123. ASIN B0006PAOYQ.

- Holzapfel, Richard Neitzel (January 1999). A History of Utah County (PDF). Utah Centennial County History Series. Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society. p. 20. ISBN 0-913738-09-3. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- Thompson, George A. (November 1982). Some Dreams Die: Utah's Ghost Towns and Lost Treasures. Salt Lake City: Dream Garden Press. p. 184. ISBN 0-942688-01-5.

- Haddock, Sharon (October 28, 2004). "Cemetery on brink of oblivion". Deseret Morning News. Retrieved May 29, 2008.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Forest City, Utah. |