Food powder

Food powder or powdery food is the most common format of dried solid food material that meets specific quality standards, such as moisture content, particle size, and particular morphology.[1] Common powdery food products include milk powder, tea powder, cocoa powder, coffee powder, soybean flour, wheat flour, and chili powder.[1] Powders are particulate discrete solid particles of size ranging from nanometres to millimetres that generally flow freely when shaken or tilted. The bulk powder properties are the combined effect of particle properties by the conversion of food products in solid state into powdery form for ease of use, processing and keeping quality.[2] Various terms are used to indicate the particulate solids in bulk, such as powder, granules, flour and dust, though all these materials can be treated under powder category. These common terminologies are based on the size or the source of the materials.

The particle size, distribution, shape and surface characteristics and the density of the powders are highly variable and depend on both the characteristics of the raw materials and processing conditions during their formations. These parameters contribute to the functional properties of powders, including flowability, packaging density, ease of handling, dust forming, mixing, compressibility and surface activity.[3]

Characteristics

Microstructure

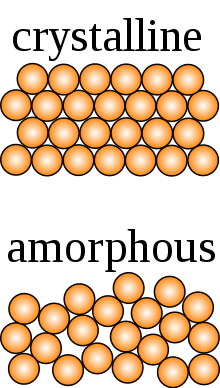

Food powder may be amorphous or crystalline in their molecular level structure. Depending on the process applied, the powders can be produced in either of these forms. Powders in crystalline state possess defined molecular alignment in the long-range order, while amorphous state is disordered, more open and porous. Common powders found in crystalline states are salts, sugars and organic acids. Meanwhile, many food products such as dairy powders, fruit and vegetable powders, honey powders and hydrolysed protein powders are normally in amorphous state.[4] The properties of food powders including their functionality and their stability are highly dependent on these structures. Many of the desired and important properties of the food materials can be achieved by altering these structures.

Powder surface composition and total surface area

Powder is a particulated food with a large interfacial area. Food is a composite mixture of mainly protein, carbohydrate, fat and minerals. These components can absorb water molecules in their active hydration sites. The amount and rate of water adsorption depends on the bulk and particles’ surface composition, total particle surface area (particle size), internal porosity and molecular structure. As the particulated foods (powders) have a larger surface area and broken chemical structure at the interface compared with the bulk food, water hydration rate and absolute hydration capacity is larger than in the bulk material of same species.[4]

Powder also has a composite surface with various sized capillaries and geometrical patterns which results in slow penetration of water. Powders with a high amount of low molecular weight carbohydrates or protein are hygroscopic (uptake moisture quickly), thus dissolve with ease. Crystalline powders are slow to dissolve because the dissolution needs to progress from outside to inside as the water molecules cannot penetrate quickly due to the tight molecular structure of crystals.[4]

Formation

In many processing situations, the powder forms are essential, such as in mixing and dissolution. Powder particles are created from bulk solid materials by dehydration and grinding.

Dehydration

Drying (dehydrating) is one of the oldest and easiest methods of food preservation. Dehydration is the process of removing water or moisture from a food product by heating at right temperature as well as containing air movement and dry air to absorb and carry the released moisture away.[5] Reducing the moisture content of food prevents the growth of microorganisms such as bacteria, yeast and molds and slows down enzymatic reactions that take place within food. The combination of these events helps to prevent spoilage in dried food.

The foods can be dried using several methods either in the sun or oven or even food dehydrator. However, sun dried method requires warm days of 29.4 °C or higher, low humidity and insect control while oven-baked is less efficient as it may destroy the nutrients of the food.[6] It is recommended to use electric hot air food dehydrator which is simple and easy to design, construct and maintain.[7] In fact, it is very affordable and has been reported to retain most of the nutritional properties of food if dry using appropriate drying conditions.

Grinding

Grinding is the process of breaking solid food items into smaller particles including powders by using food processors.

See also

References

- Su, Wen-Hao; Sun, Da-Wen (January 2018). "Fourier Transform Infrared and Raman and Hyperspectral Imaging Techniques for Quality Determinations of Powdery Foods: A Review: T-IR and Raman HSI techniques…". Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 17 (1): 104–122. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12314.

- Bhandari, Bhesh R; Bansal, Nidhi; Zhang, Min; Schuck, Pierre (2013-08-31). Handbook of Food Powders: Processes and Properties. ISBN 9780857098672.

- Roos, Yrö H. (1995). "Mechanical Properties". Phase Transitions in Foods. Phase Transitions in Foods. Elsevier. pp. 247–270. doi:10.1016/b978-012595340-5/50008-0. ISBN 9780125953405.

- Gaiani, C; Burgain, J; Scher, J (2013). "Surface composition of food powders". Handbook of Food Powders. pp. 339–378. doi:10.1533/9780857098672.2.339. ISBN 9780857095138.

- Berk, Zeki (2013). "Dehydration". Food Process Engineering and Technology. Food Process Engineering and Technology. Elsevier. pp. 511–566. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-415923-5.00022-8. ISBN 9780124159235.

- Umesh Hebbar, H.; Rastogi, Navin K. (2012). "Microwave Heating of Fluid Foods". Novel Thermal and Non-Thermal Technologies for Fluid Foods. Novel Thermal and Non-Thermal Technologies for Fluid Foods. Elsevier. pp. 369–409. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-381470-8.00012-8. ISBN 9780123814708.

- Sancho-Madriz, M.F. (2003). "Preservation of Food". Encyclopedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition. Encyclopedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition. Elsevier. pp. 4766–4772. doi:10.1016/b0-12-227055-x/00968-8. ISBN 9780122270550.