Florence Shotridge

Florence Scundoo Shotridge (1882–1917) was a Native Alaskan Tlingit ethnographer, museum educator, and weaver. From 1911 to 1917, she worked for the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (the Penn Museum). In 1905, she demonstrated Chilkat weaving at the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, Oregon. In 1916, she co-directed with her husband Louis Shotridge a collecting expedition to southeast Alaska that was funded by the retail magnate and Penn Museum trustee, John Wanamaker.[1] In 1913, Florence and Louis Shotridge co-authored an ethnographic article entitled, “Indians of the Northwest” which appeared in the University of Pennsylvania's Museum Journal. In the same issue, Florence Shotridge independently published an article entitled, “The Life of a Chilkat Indian Girl,”[2] in which she discussed both puberty customs for Tlingit girls as they transitioned into womanhood and Tlingit expectations for female behavior.

Florence Scundoo Shotridge | |

|---|---|

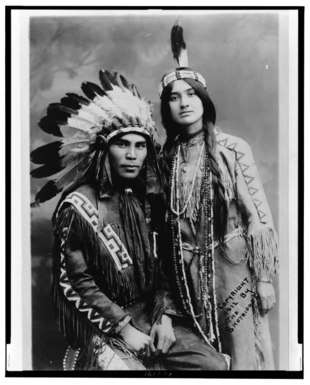

_LCCN2014686695.jpg) Florence Scundoo Shotridge sitting with her Chilkat blanket. | |

| Born | 1882 |

| Died | 1917 (aged 34–35) |

| Occupation | Ethnographer museum educator weaver |

Family, Education, and Home Town

Florence (“Suzie”) Scundoo (Kaatxwaaxsnéi) was born in Haines, Alaska in 1882. She was the daughter of a high-ranking shaman of the Mountain house clan of Chilkat, and she came from the Raven moiety. Her Tlingit given name, Kaatxwaaxsnéi, referred to a ceremony held on a special occasion, when clan elders would mix powdered abalone and clam shells with tobacco to be smoked. From her mother, Florence learned the arts of Chilkat beading and blanket weaving.[1][3]

In Haines, Scundoo attended the Presbyterian Mission School for four years. There she excelled in both singing and piano, and learned to speak English. At this school, Florence met fellow student Louis Shotridge, who also belonged to a high-ranking Chilkat family, and to whom her parents had already betrothed her when she was a child.[4] They married on December 25, 1902.[5]

The town of Haines, where Florence was born and raised, and where she later died, grew during the Klondike Gold Rush of 1896. The town enjoyed a position on the Alaskan panhandle where the Chilkat Tlingit people could mediate between coastal and inland groups. During Florence's youth, Haines began to receive an influx of tourists, who were eager to buy Native Alaskan crafts; the economy of the town also relied on canneries, which were depleting the local salmon stocks.[3]

The U.S. government, which bought Alaska from Russia in 1867,[6] banned the use of the Tlingit language and promoted English instead.[3] Presbyterian missionaries, who started work in Haines in 1878, promoted the U.S. government's social objectives not only by trying to spread Christianity among native peoples but also by promoting English-language education and associated Anglo-American customs. These circumstances help to explain how Florence – who attended the mission school for four years, in contrast to Louis, who attended for only seventeen months – developed a relatively strong command of both spoken and written English at a time when many Chilkat people still did not know English.[3]

Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition

Alaska governor John Brady met Florence Shotridge in 1905 when she was living in Haines. At the time, he was looking for an Indian woman skilled in Chilkat weaving to represent Alaska at the Louis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, Oregon. He also needed someone who could speak English to visitors at this fair. Brady chose Florence Shotridge, one of the few Chilkat females who could weave and speak English fluently, a result of her having attended the Presbyterian mission school in Haines.[1]

Florence Shotridge attended the Centennial Exposition with her husband Louis, who brought several Tlingit craft items with the idea of selling them to collectors. It was there in Portland that they met George Byron Gordon, director of the Penn Museum, who was planning a trip to Alaska to purchase materials. The Shotridges developed a rapport with Gordon, who bought forty-nine Alaskan objects from them for the Penn Museum.[3]

Career

Lacking employment when the Lewis and Clark Exposition ended, Florence and Louis Shotridge took a series of temporary jobs during the years from 1906 to 1913 and hired a tutor to improve their English skills.[7] They joined Antonio Apache’s Indian Crafts Exhibition in Los Angeles in 1906, as well as a variety of other Indian craft fairs. They performed with a traveling Indian grand opera company in 1911, with Florence playing piano and Louis singing in baritone. They also attended the World in Cincinnati Exposition in 1912.[3]

In 1912, Florence and Louis Shotridge visited New York and then Philadelphia, where they stayed with the University of Pennsylvania anthropologist Frank Speck. The Penn Museum director, George Byron Gordon, hired Louis Shotridge on a temporary basis, and later in 1915 gave him a full-time job as an Assistant Curator and cataloguer of the American section of the Penn Museum. Florence worked at the Museum in a voluntary capacity, helping Louis with his work and guiding groups of schoolchildren on tours of the museum. She often dressed in Plains (not Northwest) Indian clothing to appeal to visitors who called her the “Indian Princess”. Meanwhile, Louis took classes in the Wharton School of Business where he aimed to develop skills as an entrepreneur that he could use in Alaska.[1][4][3]

At a time when the Penn Museum was expanding its public outreach programs, Florence and Louis Shotridge performed Native American folkways for Penn Museum visitors. Photographs show that Florence and Louis Shotridge sometimes wore Plains Indian outfits, with leather, beadwork, and feathered decorations, which were quite different from the Tlingit clothing of Alaska. Florence, in particular, often led groups of schoolchildren through the museum while she dressed up in Native American outfits.[1]

In 1916, Florence and Louis Shotridge set out for Alaska on a collecting trip funded by the retail magnate and Philadelphia philanthropist, John Wanamaker. The Shotridge Expedition was the first anthropological expedition led by Native Americans. The expedition entrusted Louis and Florence with the task of collecting ethnographic objects and gathering detailed information on myths and religious beliefs. Suffering from a case of tuberculosis, which she had contracted years before, Florence spent this trip in ill health and ultimately died in Haines, Alaska, in a house that the Shotridges had built.[3]

Publications

With her husband Louis Shotridge, Florence Shotridge published a short ethnographic study entitled “Indians of the Northwest” in the University of Pennsylvania’s Museum Journal in 1913.[8] Their study attracted attention from the French scholar Poutrin, who published a review in the Journal de la Société des Américanistes.[9] This French anthropological journal was the publication of the Société des Américanistes (Society of Americanists), founded in 1895, which continues to flourish today under the aegis of the Musée du Qual Branly Jacques Chirac in Paris.[10] Poutrin praised their article for describing Tlingit material culture, including the construction of houses, and familial culture, including the organization of totemic clans.

The article on “Indians of the Northwest” cited Louis Shotridge as the first author. Yet on the basis of its prose, the anthropologist Maureen E. Milburn concluded that its actual writer was Florence Shotridge, “whose clear, expository style was different from that of her husband’s.”[3]

Shotridge also published a short article entitled “The Life of a Chilkat Indian Girl” in the same 1913 issue of the Museum Journal.[2] The French scholar Dr. Poutrin praised this article for showing “the soul of the Indian hidden from strangers.” [11] Florence Shotridge claimed in this text that Chilkat society sharply discouraged girls from talking loudly and prized silence and decorum in women. She described how girls upon puberty underwent a period of training of four to twelve months during which they engaged in seclusion, fasting, training in manners, and instruction in making a ceremonial outfit or object. At the end of this period, females engaged in the custom of “coming out”, dressed in a hooded leather robe, to signal entry into womanhood. Florence Shotridge concluded her essay by noting that with the appearance of Christian missionaries, who disapproved of these practices, the customs that she described were vanishing.

Weaving: The Chilkat Blanket

Florence Shotridge was a skilled weaver, beader, and basket maker who learned traditional Chilkat arts from her mother. In 1905, while living in Haines, Alaska, she met John G. Brady (governor of Alaska from 1897 to 1906) who was looking for Native Alaskans to represent the cultural traditions of the state at the 1905 Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, Oregon. Brady recruited Florence Shotridge to demonstrate Chilkat weaving, as she was the only one in her tribe who spoke English, and invited her husband Louis along, to describe Tlingit masks and dyes.[1]

It was at this exposition that the Shotridges met George Byron Gordon, director of the Penn Museum, who later hired Louis in Philadelphia in 1912. Louis Shotridge, who outlived Florence by twenty-two years, published over a dozen ethnographic articles and went on to become the subject of many academic studies. And yet, in the words of the anthropologist Elizabeth P. Seaton, “It was in fact Florence’s skill at weaving which initiated the Shotridges’ relationship with the world of anthropological trade.”[1]

Florence Shotridge began weaving the blanket in Portland, and finished the piece in Los Angeles at the Indian Crafts Exhibition. She made the blanket itself with cedar bark and with wool that she spun from five wild mountain goats. The black dye came from the bark of the spruce tree, and the vibrant yellow color was extracted from a yellow moss found only in Alaska. The moss is hard to extract and therefore the dye that comes from it is rare and expensive. The pattern on the blanket mimicked her father’s family emblem, or totem. Later, in an interview with the newspaper known as The North American, she reported that she spent eight months weaving the blanket, spending an average of six hours per day working on it. She also valued the blanket at $1,500.[7]

In 1911, Louis Shotridge asked the Penn Museum’s director, George Byron Gordon, to buy the Chilkat blanket which had taken Florence many months to weave, first, at the Lewis and Clark Exposition and later, in Los Angeles (where she completed it). Gordon declined, but in 1914, the anthropologist Edward Sapir (who had been based in the Penn Museum until 1910) bought Florence’s blanket instead. At the time, Sapir was head of the anthropology division in Ottowa’s Victoria Memorial Museum. Known today as Canadian Museum of History, this institution in Ottowa preserves Florence Shotridge’s blanket as “Chilkat Robe”, Artifact VII-A-131.[12] The same museum also preserves a description of the blanket, called “The Tina Blanket”, that Florence wrote. In her account she described its iconography, which included the grizzly bear crest of her father’s house.[2]

Death and Legacy

By the time Florence and Louis Shotridge set out on the Wanamaker-funded expedition to Alaska in 1916, Florence Shotridge was struggling with a case of tuberculosis that she had contracted many years before. She died several months later, in Haines, in 1917. “Minnehaha Is Dead”, declared an obituary that appeared in a Philadelphia newspaper,[13] calling her by the name of the central female character in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1855 epic poem, Hiawatha.

As the Mexican filmmaker Pablo Helguera demonstrated in a video documentary called What in the World that he produced about the Penn Museum in 2010, Florence Shotridge’s work largely catered to non-Native audiences. With her husband Louis, Helguera argued, Florence Shotridge was “playing to others’ expectations as to what constitutes Indian-ness” and in that way that “enact[ed] Anglo-American desires for a pure, unsullied order.”[14]

Writing in 2001, the anthropologist Elizabeth Seaton observed that Florence Shotridge, during her short career at the Penn Museum after 1912, had been a “‘museum Indian’ – a living ethnographic exhibit of sorts” who cultivated stereotypes about Native Americans as alternately primitive, exotic, and erotic. Her self-staging of abstract and generalized Native American life for museum audiences, combined with her career as a collector of Native Alaskan artistic and cultural objects for a distant museum, has endowed her career as an ethnographer and performer with ambiguity and even controversy.

References

- Seaton, Elizabeth (2001). "The Native Collector: Louis Shotridge and the Contests of Possession". Ethnography. 2 (1): 35–61.

- Shotridge, Florence (September 1913). "The Life of a Chilkat Indian Girl". The Museum Journal. 4 (3): 101–103.

- Milburn, Maureen E. (1994). Dauenhauer, Nora Marks; Dauenhauer, Richard (eds.). "Weaving the 'Tina' Blanket: The Journey of Florence and Louis Shotridge." In: Haa Kusteeyí, Our Culture: Tlingit Life Stories. Seattle: University of Washington Press. pp. 548–64.

- Preucel, Robert W. (2015). "Shotridge in Philadelphia: Representing Native Alaskan People to East Coast Audiences" in Sharing Our Knowledge: The Tlingit and Their Coastal Neighbors. Omaha: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 41–78.

- "Louis V Shotridge". The Penn Museum.

- "Treaty with Russia for the Purchase of Alaska: Primary Documents of American History (Virtual Programs & Services, Library of Congress)". www.loc.gov. Retrieved 2020-02-25.

- Smith, Maude (January 1912). "A Little Chat with Katkwachsnea". The North American.

- Shotridge, Louis; Shotridge, Florence (1913). "Indians of the Northwest". University of Pennsylvania Museum Journal. 4:3: 71–99.

- Poutrin, Dr. (1919). "Review of Louis and Florence Shotridge, Indians of the Northwest (University of Pennsylvania, The Museum Journal, 4 [1913], pp. 70-103". Journal de la Société des Américanistes. 11: 295–96.

- "Société des Américanistes". www.quaibranly.fr (in French). Retrieved 2020-03-04.

- Poutrin (1913). "Indians of the Northwest". University of Pennsylvania, The Museum Journal. 4: 70–103.

- Canadian Museum of History/Musée Canadien de l'Histoire (March 3, 2020). "Chilkat Robe". Canadian Museum of History/Musée Canadien de l'Histoire. [Canadian Museum of History/Musée Canadien de l'Histoire Archived] Check

|archive-url=value (help) from the original on March 3, 2020. Retrieved March 3, 2020. - "'Minnehaha' Dead in Alaska". Telegraph. June 14, 1917 – via Alaska Historical Library.

- Helguera, Pablo (2010). "What in the World, Part 2". Penn Museum. Retrieved March 3, 2020.