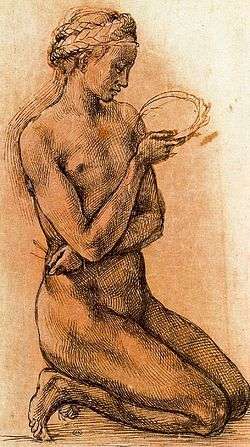

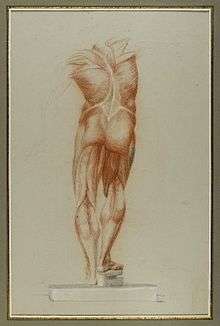

Figure study

A figure study is a drawing or painting of the human body made in preparation for a more composed or finished work;[1] or to learn drawing and painting techniques in general and the human figure in particular. By preference, figure studies are done from a live model, but may also include the use of other references[2] and the imagination of the artist. The live model may be clothed, or nude, but is usually nude for student work in order to learn human anatomy.

A related term in sculpture is a maquette, a small scale model or rough draft of a proposed work. Drawings may also be preparatory for sculptural work.

Preparatory studies may be compositional, representing the entire proposed work, or may only be of certain details, such as hands and feet. Studies may be sketches completed in a relatively short length of time, or very detailed depending upon the artist's preferred methods. Drawings may concentrate on shapes and form, while studies in painting media are about color and lighting.

The term figure study is sometimes used in photography,[3] but does not seem to be clearly defined as different from nude photography in general, given the inherently finished nature of the medium. Photography students may do work that is for educational purposes, and an artist may take photographs with the intent of using them as references for paintings, but the terms figure study or nude study is usually not limited to these preparatory or educational photos. This usage may have begun in the 19th century, when some photographers called their nude images “studies for artists” merely to evade the censors.[4]

Education

Beginning in the Renaissance[5] drawing the figure from life has been considered the best way to learn how to draw, and the practice has been maintained into the present. Different drawing techniques and exercises have become standard, including gesture, contour, and mass drawings. For beginners first learning to draw, learning to correctly observe real objects is essential in order to learn three dimensional perspective and the effects of lighting. Live models are preferred but if not available, plaster casts of the figure may be used, never photographs.[6]

Open drawing groups

Experienced artists continue to practice drawing the figure long after their formal education is completed by attending informal groups with no instruction that meet, often weekly, to share the cost of hiring a model. Known by various names, such as sketch groups, figure sessions, etc.; the format is similar to beginning or intermediate drawing classes, being three hours in total that start with a number of gestures and proceed to slightly longer poses, but rarely more than 20 minutes each, only time enough for studies. Such open drawing groups can be found in many locals in the United States,[7] and in other countries that share the Western tradition of figure studies.[8]

Preparatory

During the 16th to the 19th centuries, painters did numerous drawings and color studies in preparation for large works that might take a year or more to complete.[9] Since the late 19th century studies have become less important as painters adopted of the wet-on-wet, or alla prima painting technique, in which layers of wet paint are applied to previous layers of wet paint, the sketch being merely the first layer. However, the use of studies has been maintained by the academic art tradition.

- Color Studies

Study of a Figure Outdoors (Facing Right) (1886) by Claude Monet

Study of a Figure Outdoors (Facing Right) (1886) by Claude Monet Prostitutes (c1895) by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Prostitutes (c1895) by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec_-_ritratto_di_Nicola_D'Inverno_(1892).jpg) A watercolor figure study by John Singer Sargent.

A watercolor figure study by John Singer Sargent.

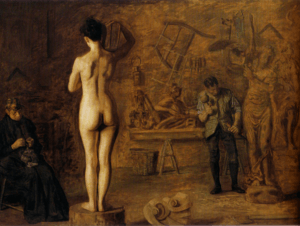

- Study and Completed Painting

Study for William Rush Carving His Allegorical Figure of the Schuylkill River by Thomas Eakins

Study for William Rush Carving His Allegorical Figure of the Schuylkill River by Thomas Eakins William Rush Carving His Allegorical Figure of the Schuylkill River (1908)

William Rush Carving His Allegorical Figure of the Schuylkill River (1908)

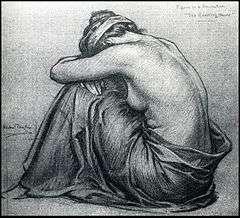

- Drawings

Madame Palmyre with Her Dog (1897) by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Madame Palmyre with Her Dog (1897) by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec Figure Study by Herbert James Draper

Figure Study by Herbert James Draper

Notes

- Berry, Ch. 8

- "Snapshot:Painters and Photography, Bonnard to Vuillard". The Phillips Collection. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- "In Focus: The Nude". The J Paul Getty Museum.

- "Naked before the Camera". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Bambach, Carmen. "Anatomy in the Renaissance". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- Nicolaides

- "Figure drawing sessions and walk in ateliers". Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- Steinhart

- "The Aesthetic of the Sketch in Nineteenth-Century France". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

References

- Berry, William A. (1977). Drawing the Human Form: A Guide to Drawing from Life. New York: Van Nortrand Reinhold Co. ISBN 0-442-20717-4.

- Nicolaides, Kimon (1969). The Natural Way to Draw. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. ISBN 0-395-20548-4.

- Steinhart, Peter (2004). The Undressed Art: Why We Draw. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 1-4000-4184-8.

Further reading

- Clark, Kenneth (1956). The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01788-3.

- Jacobs, Ted Seth (1986). Drawing with an Open Mind. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications. ISBN 0-8230-1464-9.

- Scala, Mark, ed. (2009). Paint Made Flesh. Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 978-0826516220.

External links

- "Preparatory Study, Painting in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History - Index Classification: Material and Technique". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- Bambach, Carmen. "Renaissance Drawings: Material and Function". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 4 November 2012.