Fibration

In topology, a branch of mathematics, a fibration is a generalization of the notion of a fiber bundle. A fiber bundle makes precise the idea of one topological space (called a fiber) being "parameterized" by another topological space (called a base). A fibration is like a fiber bundle, except that the fibers need not be the same space, nor even homeomorphic; rather, they are just homotopy equivalent. Weak fibrations discard even this equivalence for a more technical property.

Fibrations do not necessarily have the local Cartesian product structure that defines the more restricted fiber bundle case, but something weaker that still allows "sideways" movement from fiber to fiber. Fiber bundles have a particularly simple homotopy theory that allows topological information about the bundle to be inferred from information about one or both of these constituent spaces. A fibration satisfies an additional condition (the homotopy lifting property) guaranteeing that it will behave like a fiber bundle from the point of view of homotopy theory.

Fibrations are dual to cofibrations, with a correspondingly dual notion of the homotopy extension property; this is loosely known as Eckmann–Hilton duality.

Formal definition

A fibration (or Hurewicz fibration or Hurewicz fiber space, so named after Witold Hurewicz) is a continuous mapping satisfying the homotopy lifting property with respect to any space. Fiber bundles (over paracompact bases) constitute important examples. In homotopy theory, any mapping is 'as good as' a fibration—i.e. any map can be decomposed as a homotopy equivalence into a "mapping path space" followed by a fibration into homotopy fibers.

The fibers are by definition the subspaces of E that are the inverse images of points b of B. If the base space B is path connected, it is a consequence of the definition that the fibers of two different points and in B are homotopy equivalent. Therefore, one usually speaks of "the fiber" F.

Serre fibrations

A continuous mapping with the homotopy lifting property for CW complexes (or equivalently, just cubes ) is called a Serre fibration or a weak fibration, in honor of the part played by the concept in the thesis of Jean-Pierre Serre. This thesis firmly established in algebraic topology the use of spectral sequences, and clearly separated the notions of fiber bundles and fibrations from the notion of sheaf (both concepts together having been implicit in the pioneer treatment of Jean Leray). Because a sheaf (thought of as an étalé space) can be considered a local homeomorphism, the notions were closely interlinked at the time. One of the main desirable properties of the Serre spectral sequence is to account for the action of the fundamental group of the base B on the homology of the "total space" E.

Note that Serre fibrations are strictly weaker than fibrations in general: the homotopy lifting property need only hold on cubes (or CW complexes), and not on all spaces in general. As a result, the fibers might not even be homotopy equivalent; an explicit example is given below.

Examples

In the following examples, a fibration is denoted

- F → E → B,

where the first map is the inclusion of "the" fiber F into the total space E and the second map is the fibration onto the basis B. This is also referred to as a fibration sequence.

- The projection map from a product space is very easily seen to be a fibration.

- Fiber bundles have local trivializations, i.e. Cartesian product structures exist locally on B, and this is usually enough to show that a fiber bundle is a fibration. More precisely, if there are local trivializations over a numerable open cover of B, the bundle is a fibration. Any open cover of a paracompact space has a numerable refinement. For example, any open cover of a metric space has a locally finite refinement, so any bundle over such a space is a fibration. The local triviality also implies the existence of a well-defined fiber (up to homeomorphism), at least on each connected component of B.

- The Hopf fibration S1 → S3 → S2 was historically one of the earliest non-trivial examples of a fibration.

- Hopf fibrations generalize to fibrations over complex projective space, with a fibration S1 → S2n+1 → CPn. The above example is a special case, for n=1, since CP1 is homeomorphic to S2.

- Hopf fibrations generalize to fibrations over quaternionic projective space, with a fibration Sp1 → S4n+3 → HPn. The fiber here is the group of unit quaternions Sp1.

- The Serre fibration SO(2) → SO(3) → S2 comes from the action of the rotation group SO(3) on the 2-sphere S2. Note that SO(3) is homeomorphic to the real projective space RP3, and so S3 is a double-cover of SO(3), and so the Hopf fibration is the universal cover.

- The previous example can also be generalized to a fibration SO(n) → SO(n+1) → Sn for any non-negative integer n (though they only have a fiber that isn't just a point when n > 1) that comes from the action of the special orthogonal group SO(n+1) on the n-sphere.

Turning a map into a fibration

Any continous map can be factored as a composite [1] where is a fibration and is a homotopy equivalence. Denoting as the mapping space (using the compact-open topology), the fibration space is constructed as

with structure map sending

Using the homotopy lifting property, it can be checked this maps actually forms a fibration. The injection map is given by

where is the constant path. There is a deformation retract of the homotopy fibers

to this inclusion, giving a homotopy equivalence .

Weak fibration example

The previous examples all have fibers that are homotopy equivalent. This must be the case for fibrations in general, but not necessarily for weak fibrations. The notion of a weak fibration is strictly weaker than a fibration, as the following example illustrates: the fibers might not even have the same homotopy type.

Consider the subset of the real plane given by

and the base space given by the unit interval , the projection by . One can easily see that this is a Serre fibration. However, the fiber and the fiber at are not homotopy equivalent. The space has an obvious injection into the total space and has an obvious homotopy (the constant function) in the base space ; however, it cannot be lifted, and thus the example cannot be a fibration in general.

Long exact sequence of homotopy groups

Choose a base point b0 ∈ B. Let F refer to the fiber over b0, i.e. F = p−1({b0}); and let i be the inclusion F → E. Choose a base point f0 ∈ F and let e0 = i(f0). In terms of these base points, the Puppe sequence can be used to show that there is a long exact sequence

It is constructed from the homotopy groups of the fiber F, total space E, and base space B. The homomorphisms πn(F) → πn(E) and πn(E) → πn(B) are just the induced homomorphisms from i and p, respectively. The maps involving π0 are not group homomorphisms because the π0 are not groups, but they are exact in the sense that the image equals the kernel (here the "neutral element" is the connected component containing the base point).

This sequence holds for both fibrations, and for weak fibrations, although the proof of the two cases is slightly different.

Proof

One possible way to demonstrate that the sequence above is well-defined and exact, while avoiding contact with the Puppe sequence, is to proceed directly, as follows. The third set of homomorphisms βn : πn(B) → πn−1(F) (called the "connecting homomorphisms" (in reference to the snake lemma) or the "boundary maps") is not an induced map and is defined directly in the corresponding homotopy groups with the following steps.

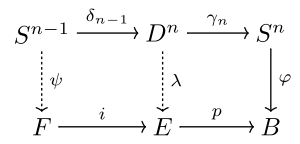

- First, a little terminology: let δn : Sn → Dn+1 be the inclusion of the boundary n-sphere into the (n+1)-ball. Let γn : Dn → Sn be the map that collapses the image of δn−1 in Dn to a point.

- Let φ : Sn → B be a representing map for an element of πn(B).

- Because Dn is homeomorphic to the n-dimensional cube, we can apply the homotopy lifting property to construct a lift λ : Dn → E of φ ∘ γn (i.e., a map λ such that p ∘ λ = φ ∘ γn) with initial condition f0.

- Because γn ∘ δn−1 is a point map (hereafter referred to as "pt"), pt = φ ∘ γn ∘ δn−1 = p ∘ λ ∘ δn−1, which implies that the image of λ ∘ δn−1 is in F. Therefore, there exists a map ψ : Sn−1 → F such that i ∘ ψ = λ ∘ δn−1.

- We define βn [φ] = [ψ].

The above is summarized in the following commutative diagram:

Repeated application of the homotopy lifting property is used to prove that βn is well-defined (does not depend on a particular lift), depends only on the homotopy class of its argument, it is a homomorphism and that the long sequence is exact.

Alternatively, one can use relative homotopy groups to obtain the long exact sequence on homotopy of a fibration from the long exact sequence on relative homotopy[2] of the pair . One uses that the n-th homotopy group of relative to is isomorphic to the n-th homotopy group of the base .

Example

One may also proceed in the reverse direction. When the fibration is the mapping fibre (dual to the mapping cone, a cofibration), then one obtains the exact Puppe sequence. In essence, the long exact sequence of homotopy groups follows from the fact that the homotopy groups can be obtained as suspensions, or dually, loop spaces.

Euler characteristic

The Euler characteristic χ is multiplicative for fibrations with certain conditions.

If p : E → B is a fibration with fiber F, with the base B path-connected, and the fibration is orientable over a field K, then the Euler characteristic with coefficients in the field K satisfies the product property:[3]

- χ(E) = χ(F) · χ(B).

This includes product spaces and covering spaces as special cases, and can be proven by the Serre spectral sequence on homology of a fibration.

For fiber bundles, this can also be understood in terms of a transfer map τ : H∗(B) → H∗(E)—note that this is a lifting and goes "the wrong way"—whose composition with the projection map p∗ : H∗(E) → H∗(B) is multiplication by the Euler characteristic of the fiber:[4] p∗ ∘ τ = χ(F) · 1.

Fibrations in closed model categories

Fibrations of topological spaces fit into a more general framework, the so-called closed model categories, following from the acyclic models theorem. In such categories, there are distinguished classes of morphisms, the so-called fibrations, cofibrations and weak equivalences. Certain axioms, such as stability of fibrations under composition and pullbacks, factorization of every morphism into the composition of an acyclic cofibration followed by a fibration or a cofibration followed by an acyclic fibration, where the word "acyclic" indicates that the corresponding arrow is also a weak equivalence, and other requirements are set up to allow the abstract treatment of homotopy theory. (In the original treatment, due to Daniel Quillen, the word "trivial" was used instead of "acyclic.")

It can be shown that the category of topological spaces is in fact a model category, where (abstract) fibrations are just the Serre fibrations introduced above and weak equivalences are weak homotopy equivalences.[5]

References

- Hatcher, Allen. Introduction to algebraic topology. p. 407.

- Hatcher, Allen (2002), Algebraic Topology (PDF)

- Spanier, Edwin Henry (1982), Algebraic Topology, Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-94426-5, Applications of the homology spectral sequence, p. 481

- Gottlieb, Daniel Henry (1975), "Fibre bundles and the Euler characteristic" (PDF), Journal of Differential Geometry, 10 (1): 39–48, doi:10.4310/jdg/1214432674

- Dwyer, William G.; Spaliński, J. (1995), "Homotopy theories and model categories", Handbook of algebraic topology, Amsterdam: North-Holland, pp. 73–126, doi:10.1016/B978-044481779-2/50003-1, ISBN 9780444817792, MR 1361887