Ferdinand Marcos' cult of personality

Ferdinand Marcos developed a cult of personality as a way of remaining President of the Philippines for 21 years,[2][3] drawing comparisons to other authoritarian leaders such as Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler,[4] but also to more contemporary dictators such as Sukarno in Indonesia, Saddam Hussein in Iraq, and the Kim dynasty of North Korea.[5](pp114)

The propaganda techniques used, either by himself or by others, to mythologize Ferdinand Marcos, begin with local political machinations in Ilocos Norte while Ferdinand was still the young son of politician Mariano Marcos,[6] and persist today in the efforts to revise the way Marcos is portrayed in Philippine history.[7]

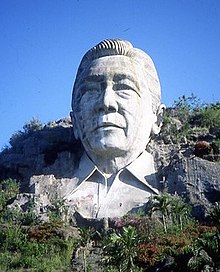

These propaganda narratives and techniques include: using red scare tactics such as red-tagging to portray activists as communists and to aggrandize the threat represented by the Communist Party of the Philippines;[8][9](p"43") using martial law to take control of mass media and silence criticism;[10] the use of foreign-funded government development projects and construction projects as propaganda tools;[11] creating an entire propaganda framework around a “new society” in which he would rule under a system of “constitutional authoritarianism”;[7][13] the perpetuation of hagiographical books and films;[14][15] the perpetuation of propaganda narratives about Marcos’ activities during World War II, which have since been proven false by historical documents;[16][17] the creation of myths and stories around himself and his family;[18][19] and portrayals of himself in coinage and even a Mount Rushmore type monument;[1] among others."

After Ferdinand Marcos’ death, propaganda efforts have been made to whitewash his place in Philippine history,[20][21] an act of historical negationism[22] commonly referred to using the more popular term “historical revisionism.”[23]

Terminology

While the widely-used term for a supporter of Ferdinand Marcos or the other members of the Marcos family is "Marcos loyalist,"[24] the term "cult of personality" refers not to people specifically, but in a broader sense to the mechanism, including the techniques and structures, used to create a heroic or idealized image of a ruler.[25] The term "Marcos revisionism"[26] or "Marcos historical revisionism"[27][28] have been used to refer to the Marcos family's propaganda after their return to Philippine politics, if it is intended to revise or reframe the historical facts of Marcos' life and rule.[29][23]

Early political career

Clentelism

As with most Philippine politicians of his era Ferdinand Marcos achieved success largely by taking advantage of the client-patron relationships which dominated Philippine politics after Philippine independence.[30](p96)

Once he achieved government authority, he used it to reward his supporters[30](pp96,76) while limiting the power of other social groups and institutions.[30](p76) He styled himself as the Ilocos region’s ticket to political prominence. In his first campaign, running for congressman of his family’s already-established bailiwick, Ilocos Norte, "This is only a first step. Elect me a congressman now, and I pledge you an Ilocano president in 20 years."[31][32]

On a more personal level, Marcos established relationships with the graduate officers and junior officers of the Philippine Military Academy early on.[30](p96) When he became president, Marcos appointed mostly Ilocano commanders to head the armed forces, such that 18 out of 22 generals of the Philippine Constubulary came from the Ilocos region and House Speaker Jose B. Laurel was alarmed enough to file a 1968 bill calling for the equal represneation of all regions in the armed forces.[30](p96)[33]

He also established a small group of supporters in the business sector, whom he would later enable to establish monopolies in key economic sectors, wresting control from the political families which held them prior.[30](p96)

Early hagiographical media

A notable propaganda technique used by both candidates in the 1965 Philippine Presidential Election was the use of hagiographies, so much so that it was dubbed a “battle of books and film.” Marcos was the first to use this tactic with the book “For Every Tear a Victory: The Story of Ferdinand E. Marcos,” which was followed by a film adaptation “Iginuhit ng Tadhana (Destined).” Diosdado Macapagal countered with the propaganda film “Daigdig ng Mga Api (World of the Oppressed),” but it was Marcos who won the election.[34]

During the Martial Law era

Ideologies of "Bagong Lipunan" and "Constitutional Authoritarianism"

Among Marcos' rationalizations for the declaration of martial law were the linked ideologies of the "bagong lipunan" ("new society")[35](p"66") and of "constitutional authoritarianism."

Marcos said that there was a need to "reform society"[35](p"66") by placing it under the control of a "benevolent dictator" in a "constitutional authority" which could guide the undisciplined populace through a period of chaos.[35](p"29")[36] He referred to this social engineering exercise as the "bagong lipunan" or "new society."[37](p13)

The Philippine education system underwent a major period of restructuring in after the declaration of Martial Law in 1972,[38] in which the teaching of civics and history was reoriented [38][39] so that it would reflect values which supported the Bagong Lipunan and its ideology of constitutional authoritarianism.[40](p414) In addition, it attempted to synchronize the educational curriculum with the administration’s economic strategy of labor export.[38]

The Marcos administration also produced an array of propaganda materials - including speeches, books, lectures, slogans, and numerous propaganda songs - to promote it.[37](p13)[41]

Control of Mass media

Marcos took control of the mass media to silence public criticism during what what considered the "dark days of martial law."[42] Upon declaring martial law, Marcos arrested journalists and took control of media outlets. This allowed him to have the final say on what passed as truth.[43] According to journalism professor Luis Teodoro, the martial law period savaged the Bill of Rights and institutions of liberal democracy, such as the press.[44] Challenges to the dictatorship in the media would come from the underground press[45] and, later on, from the above-ground mosquito press.[46]

Shutdown of media outlets and the attack on journalists

On the morning of September 23, 1972, Marcos' soldiers arrested journalists and raided and padlocked media outlets across the Philippines.[47] Joaquin Roces, Teodoro Locsin Sr., Maximo Soliven, Amando Doronila, and other members of the media were rounded up and detained in Camp Crame together with members of the political opposition.[48]

Marcos' order to take over newspapers, magazines, radio and television facilities under Letter of Instruction No. 1 was done with the express purpose of preventing the undermining of the people’s faith and confidence in the regime.[49][50]

During martial law, the dictator shut down 7 major English and 3 Filipino newspapers, 1 English-Filipino newspaper, 11 English weekly magazines, 1 Spanish daily, 4 Chinese newspapers, 3 business publications, 1 news service, 7 television stations, 66 community newspapers, and 292 radio stations around the country.[51] Journalists were jailed, tortured, killed, or "disappeared" by the dictatorship.[52][53]

The crony press and censorship

The dictatorship also exercised blanket censorship through Letter of Instruction No. 1 and the Department of Public Information's Order No. 1, issued on September 25, 1972.[54] Only news outlets owned by Marcos' cronies were allowed to resume operations, such as the Philippine Daily Express owned by crony Roberto Benedicto.[55]

Construction projects as propaganda

Marcos projected himself to the Philippine public as having spent a lot on construction projects.[34](p128) This focus on infrastructure, which critics saw as a propaganda technique, eventually earned the colloquial label "edifice complex".[56][57][11]

Most of these infrastructure projects and monuments were paid for using foreign currency loans[58][56] and at great taxpayer cost.[57][13](p89) This greatly increased the Philippines’ foreign deficit - from $360 million when Marcos became president, to around $28.3 billion when he was overthrown.[59]

Historical negationism after Marcos' death

After Ferdinand Marcos’ death in 1989, propaganda efforts have been made to whitewash his place in Philippine history,[20][21] an act of historical negationism[22] commonly referred to using the more popular term “historical revisionism.”[23]

See also

References

- Cimatu, Frank; Santos-Doctor, Joya (1 January 2003). "Philippines' 'Ozymandias' still haunts". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- Root, Hilton L., Three Asian Dictators: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (January 16, 2016). http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2716732

- Mark M. Turner (1990) Authoritarian rule and the dilemma of legitimacy: The case of President Marcos of the Philippines, The Pacific Review, 3:4, 349-362, DOI: 10.1080/09512749008718886

- https://usa.inquirer.net/13895/strongmen-hitler-stalin-marcos-character-study

- Raymond, Walter John (1992) Dictionary of Politics: Selected American and Foreign Political and Legal Terms. ISBN 9781556180088

- https://www.philstar.com/other-sections/news-feature/2016/07/04/1599425/file-no-60-family-affair

- https://www.esquiremag.ph/politics/opinion/marcos-propaganda-a1576-20160923-lfrm2

- http://csreports.aspeninstitute.org/Dialogue-on-Diplomacy-and-Technology/2014/participants/details/262/Richard-Kessler

- John), Kessler, Richard J. (Richard (1989). Rebellion and repression in the Philippines. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300044065. OCLC 19266663.

- San Juan Jr., E. (1978) https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064227808532787

- Lico, Gerard (2003). Edifice Complex: Power, Myth, and Marcos State Architecture. University of Hawaii Press.

- Romero, Jose V., Jr. (2008). Philippine political economy. Quezon City, Philippines: Central Book Supply. ISBN 9789716918892. OCLC 302100329.

- Curaming, Rommel A. Power and Knowledge in Southeast Asia: State and Scholars in Indonesia and the Philippines ISBN 9780429438196

- McCallus, J. P. (1989): “The Myths of the New Filipino: Philippine government propaganda during the Early Years of Martial Law. Philippine Quarterly of. Culture and Society 17(2): 129-48.

- https://www.nytimes.com/1986/01/23/world/marcos-s-wartime-role-discredited-in-us-files.html

- https://verafiles.org/articles/file-no-60-debunking-marcos-war-myth

- https://newslab.philstar.com/31-years-of-amnesia/malakas-at-maganda

- Rafael, Vicente L. (April 1990). "Patronage and Pornography: Ideology and Spectatorship in the Early Marcos Years". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 32 (2): 282–304. doi:10.1017/S0010417500016492. ISSN 1475-2999.

- https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/philippine-govt-faces-backlash-amid-claims-that-it-is-trying-to-whitewash-history-of

- https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/09/world/asia/philippines-ferdinand-marcos-burial.html

- https://www.esquiremag.ph/politics/opinion/historical-revsionism-a1576-20161003-lfrm2

- https://thelasallian.com/2016/05/01/martial-law-and-historical-revisionism-a-holistic-understanding/

- Galam, Roderick G. (2008). "Narrating the Dictator(ship) Social Memory, Marcos, and Ilokano Literature after the 1986 Revolution". Philippine Studies. 56 (2): 151–182. ISSN 0031-7837.

- Popan, Adrian Teodor (August 2015). "The ABC of sycophancy : structural conditions for the emergence of dictators' cults of personality". doi:10.15781/T2J960G15. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "EDSA People Power: Inadequate Challenge to Marcos Revisionism". Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility. Archived from the original on

|archive-url=requires|archive-date=(help). Retrieved 2020-07-11. - "Filipinos urged to 'fight historical revisionism'". The Star. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- Pangalangan, Raphael Lorenzo A.; Fernandez, Gemmo Bautista; Tugade, Ruby Rosselle L. (2018-12-18). "Marcosian Atrocities: Historical Revisionism and the Legal Constraints on Forgetting". Asia-Pacific Journal on Human Rights and the Law. 19 (2): 140–190. doi:10.1163/15718158-01902003. ISSN 1571-8158.

- https://cmfr-phil.org/media-ethics-responsibility/journalism-review/against-rewriting-history-inquirer-on-the-marcoses-revisionism/

- Celoza, Albert F. (1997). Ferdinand Marcos and the Philippines: The Political Economy of Authoritarianism. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 9780275941376.

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1989/09/29/ferdinand-marcos-dies-in-hawaii-at-72/d1c26275-d9bd-4bfd-8934-c2a02ff4ab51/

- https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1989-09-29-8901180123-story.html

- Woo, Jongseok. (2011). Security challenges and military politics in East Asia : from state building to post-democratization. New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-1-4411-9927-0. OCLC 709938449.

- Magno, Alexander R., ed. (1998). "Democracy at the Crossroads". Kasaysayan, The Story of the Filipino People Volume 9:A Nation Reborn. Hong Kong: Asia Publishing Company Limited.

- Brillantes, Alex B., Jr. (1987). Dictatorship & martial law : Philippine authoritarianism in 1972. Quezon City, Philippines: University of the Philippines Diliman School of Public Administration. ISBN 978-9718567012.

- Beltran, J. C. A.; Chingkaw, Sean S. (2016-10-20). "On the shadows of tyranny". The Guidon. Retrieved 2020-06-20.

- Onyebadi, Uche. Music as a platform for political communication. Hershey, PA. ISBN 978-1-5225-1987-4. OCLC 972900349.

- Maca, Mark (April 2018). "Education in the 'New Society' and the Philippine Labour Export Policy (1972-1986)". Journal of International and Comparative Education. 7 (1).

- Abueva, Jose (1979). "Ideology and Practice in the 'New Society'". In Rosenberg, David (ed.). Marcos and Martial Law in the Philippines. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. pp. 35–36.Jose Abueva, "Ideology and Practice in the 'New Society'", in Marcos and Martial Law in the Philippines, edited by David Rosenberg (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1979), pp.35-—36

- Ricklefs, M. C. (2010). New History of Southeast Asia. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-137-01554-3. OCLC 965712524.

- 2018 (2018-09-11). "Listen to 'Bagong Silang,' the Most Famous of Marcos-Era Propaganda Songs". Esquire Philippines. Missing

|author1=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - "Statement: Treacherous burial mocks struggle for press freedom during Martial Law". Kodao Productions. 2016-11-22. Retrieved 2020-07-25.

- "Breaking the News: Silencing the Media Under Martial Law". Martial Law Museum. Retrieved 2020-07-25.

- Teodoro, Luis (2015-09-21). "Martial Law and the Media". AlterMidya. Retrieved 2020-07-29.

- Olea, Ronalyn V. (2012-09-28). "Underground press during martial law: Piercing the veil of darkness imposed by the dictatorship". Bulatlat. Retrieved 2020-07-29.

- Soriano, Jake (March 3, 2015). "Story of Marcos-era mosquito press relevant as ever". Yahoo News Philippines. Retrieved 2020-07-29.

- Plaza, Gerry (2020-05-07). "In Focus: Memoirs Of The 1972 ABS-CBN Shutdown". ABS-CBN. Retrieved 2020-07-25.

- "Declaration of Martial Law". Official Gazette. Retrieved 2020-07-25.

- "Letter of Instruction No. 1, s. 1972". Official Gazette. Retrieved 2020-07-25.

- "FALSE: Filipinos 'free to roam, can watch news' during Martial Law". Rappler. 2018-09-22. Retrieved 2020-07-25.

- Dizon, Nikko (2016-02-28). "Palace fighting 'disinformation' about Marcos rule". Inquirer. Retrieved 2020-07-25.

- Gonzales, Iris (2012-09-24). "Marcos atrocities: the pain continues". New Internationalist. Retrieved 2020-07-25.

- "Writers, journalists as freedom heroes". Inquirer. 2016-08-29. Retrieved 2020-07-25.

- San Juan, E. (May 1, 1978). "Marcos and the Media". Index on Censorhip. 7 (3): 39–47 – via Sage Journals.

- Pinlac, Melanie Y. (September 1, 2007). "Marcos and the Press". Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- Sudjic, Deyan (November 3, 2015). The Edifice Complex: How the Rich and Powerful Shape the World. The Penguin Press HC. ISBN 978-1-59420-068-7.

- Lapeña, Carmela G.; Arquiza, Yasmin D. (September 20, 2012). "Masagana 99, Nutribun, and Imelda's 'edifice complex' of hospitals". GMA News.

- Eduardo C. Tadem (November 24, 2016). "The Marcos debt". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- Afinidad-Bernardo, By Deni Rose M. "Edifice complex | 31 years of amnesia". The Philippine Star. Archived from the original on March 4, 2017. Retrieved April 18, 2019.