Feral parakeets in Great Britain

Feral parakeets in Great Britain are feral parakeets that are an introduced species into Great Britain. The population consists of rose-ringed parakeets (Psittacula krameri), a non-migratory species of bird that is native to Africa and the Indian Subcontinent. The origins of these birds are subject to speculation, but they are generally thought to have bred from birds that escaped from captivity.

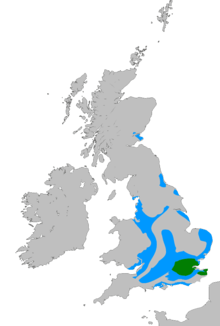

The British parakeet population is mostly concentrated in suburban areas of London and the Home Counties of South-East England, and for this reason the birds are sometimes known as "Kingston parakeets" or "Twickenham parakeets", after the London suburbs of Kingston upon Thames and Twickenham. The parakeets, which breed rapidly, have since spread beyond these areas, and flocks have been sighted in other parts of Britain. There is a flock of around 20 to 30 settled in Victoria Park, Glasgow. Other separate parakeet populations exist around other European cities.

Origin of the flocks

How exactly the parakeet population first came to exist and thrive in the wild in England is not known. Consistent with the first widespread photographs of the birds in the mid-1990s are multiple theories that a pair or more breeding parakeets escaped or were released. More specific introduction theories have been published, such as that:[1]

- parakeets escaped from the branch of Ealing Studios used for the filming of The African Queen — Isleworth Studios — in 1951[2][3][4]

- parakeets escaped from damaged aviaries during the Great Storm of 1987[2][3][4]

- a pair were released by Jimi Hendrix in Carnaby Street, London, in the 1960s[2][3][4]

- a number of birds reportedly escaped from a pet shop in Sunbury-on-Thames in 1970[5]

Romantic theories associated with film studios and rock stars are considered fanciful, however, and most ornithologists believe that the original birds probably escaped from aviaries before 1971.[6]

In terms of geographic origin, the British birds are considered a hybrid population of two Asian subspecies, P.k. borealis and P.k. manillensis.[7]

Population in Britain

Escaped parakeets have been spotted in Britain since the 19th century. The earliest recorded sighting was in 1855 in Norfolk, and parakeets were also seen in Dulwich in 1893 and Brixton in 1894. Parakeets continued to escape captivity, but populations repeatedly died out until 1969, when the species began to breed and persist in London. Beginning in Croydon, they spread to Wraysbury, Bromley and Esher.[5] The numbers remained very low, however, until the mid-1990s, when the population appeared to start increasing rapidly. The population was estimated at 500 in 1983, reached 1,500 by 1996, and 5,800 in the London area in 2002 (in up to 5 roosts).[9]

British parakeets are most common in the south-east of England, including London suburbs, Surrey, Kent and Sussex. Parakeet populations have also been reported further north in Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham, Oxford and Edinburgh.[8][3]

As parakeets are spreading and breeding so quickly, estimates of parakeet numbers vary. According to the London Natural History Society in the early 2000s, the largest population was believed to exist in the South London suburbs where, until 2007, the birds roosted principally in Esher Rugby Ground, Esher (Esher Rugby Club named its women's team "The Parakeets" in a tribute to the birds).[1][10] The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) estimates that there are around 8,600 breeding pairs in Britain.[8] Other scientific counts in 2012 have placed the number at around 32,000 birds.[4]

Ecological impact

Concerns have been raised over the impact of the growing numbers of parakeets in south-east England. Scientific research programmes have analysed the behaviour of parakeets and found that they compete with native bird species and bats for food and nesting sites. Although not aggressive, parakeets deter smaller birds with noisy gregarious behaviour, and their large size means that they often crowd small bird feeders. The detrimental effect of competitive exclusion has been likened to the impact of the introduction of grey squirrel on the red squirrel. However, British parakeets are not without natural predators; ornithologists have observed an increase in the population of birds of prey in London, and have reported sparrowhawks, peregrine falcons and hobbies preying on parakeets.[6]

Parakeets are considered a pest in many countries such as Israel, where large swarms of parakeets can have a devastating effect on certain crops, and there is concern that the rapidly growing parakeet population could have unforeseen environmental impact in Britain.[3][4] In 2009, Governmental wildlife organisation Natural England added feral parakeets to the “general licence”, a list of wild species that can be lawfully culled without the need for specific permission.[11]

See also

References

- "Tropical birds move into Surrey". BBC News. 2 October 2009. Archived from the original on 6 November 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- "Wild parrots settle in suburbs". 6 July 2004. Archived from the original on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- Copping, Jasper (20 April 2014). "Noisy parakeets 'drive away' native birds". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- Oliver, Brian (1 July 2017). "Exotic and colourful – but should parakeets be culled, ask scientists". The Observer. Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- Self, Andrew (2014). The Birds of London. A&C Black. p. 245. ISBN 9781472905147. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- McCarthy, Michael (8 June 2015). "Nature Studies: London's beautiful parakeets have a new enemy to". The Independent. Archived from the original on 31 October 2017. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- Pithon, J.A.; Dytham, C. (2001). "Determination of the origin of British feral Rose-ringed Parakeets" (PDF). British Birds. 94 (2): 74–79. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- "Ring-necked parakeet". The RSPB. Archived from the original on 10 March 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- Butler, Christopher John (2003). Population Biology of the Introduced Rose-Ringed Parakeet Psittacula krameri in the UK (PDF) (PhD). Oxford University Department of Zoology — Edward Grey Institute of Field Ornithology. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- London Bird Report 2006. London Natural History Society. 2006. p. 93. ISBN 0-901009-22-9

- "Britain's naturalised parrot now officially a pest". The Independent. 30 September 2009. Archived from the original on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Psittacula krameri in London. |

- The Great British Parakeet Invasion on YouTube

- "Spot the parakeet". BBC Black Country. Archived from the original on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- Self, Will (29 January 2016). "On location: parakeets in London - Will Self". Will-Self.com (blog). Archived from the original on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- The feral Parakeets of Battersea — blog documenting observations of the Parakeets in Battersea, London