Walking in the United Kingdom

Walking is one of the most popular outdoor recreational activities in the United Kingdom,[1] and within England and Wales there is a comprehensive network of rights of way that permits access to the countryside. Furthermore, access to much uncultivated and unenclosed land has opened up since the enactment of the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000. In Scotland the ancient tradition of universal access to land was formally codified under the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003.[2] However, there are few rights of way, or other access to land in Northern Ireland.

Walking is used in the United Kingdom to describe a range of activity, from a walk in the park to trekking in the Alps. The word "hiking" is used in the UK, but less often than walking; the word rambling (akin to roam[3]) is also used, and the main organisation that supports walking is called The Ramblers. Walking in mountainous areas in the UK is called hillwalking, or in Northern England, including the Lake District and Yorkshire Dales, fellwalking, from the dialect word fell for high, uncultivated land. Mountain walking can sometimes involve scrambling.

History

The idea of undertaking a walk through the countryside for pleasure developed in the 18th-century, and arose because of changing attitudes to the landscape and nature, associated with the Romantic movement.[4] In earlier times walking generally indicated poverty and was also associated with vagrancy.[5]

Thomas West, an English priest, popularised the idea of walking for pleasure in his guide to the Lake District of 1778. In the introduction he wrote that he aimed

to encourage the taste of visiting the lakes by furnishing the traveller with a Guide; and for that purpose, the writer has here collected and laid before him, all the select stations and points of view, noticed by those authors who have last made the tour of the lakes, verified by his own repeated observations.[6]

To this end he included various "stations" or viewpoints around the lakes, from which tourists would be encouraged to appreciate the views in terms of their aesthetic qualities.[7] Published in 1778 the book was a major success.[8]

Another famous early exponent of walking for pleasure was the English poet William Wordsworth. In 1790 he embarked on an extended tour of France, Switzerland, and Germany, a journey subsequently recorded in his long autobiographical poem The Prelude (1850). His famous poem Tintern Abbey was inspired by a visit to the Wye Valley made during a walking tour of Wales in 1798 with his sister Dorothy Wordsworth. Wordsworth's friend Coleridge was another keen walker and in the autumn of 1799, he and Wordsworth undertook a three weeks tour of the Lake District. John Keats, who belonged to the next generation of Romantic poets began, in June 1818, a walking tour of Scotland, Ireland, and the Lake District with his friend Charles Armitage Brown.

More and more people undertook walking tours through the 19th-century, of which the most famous is probably Robert Louis Stevenson's journey through the Cévennes in France with a donkey, recorded in his Travels with a Donkey (1879). Stevenson also published in 1876 his famous essay "Walking Tours". The subgenre of travel writing produced many classics in the subsequent 20th-century. An early American example of a book that describes an extended walking tour is naturalist John Muir's A Thousand Mile Walk to the Gulf (1916), a posthumous published account of a long botanising walk, undertaken in 1867.

Due to industrialisation in England, people began to migrate to the cities where living standards were often cramped and unsanitary. They would escape the confines of the city by rambling about in the countryside. However, the land in England, particularly around the urban areas of Manchester and Sheffield, was privately owned and trespass was illegal. Rambling clubs soon sprang up in the north and began politically campaigning for the legal 'right to roam'. One of the first such clubs, was 'Sunday Tramps' founded by Sir Frederick Pollock, George Croom Robertson, and Leslie Stephen in 1879.[9] The first national grouping, the Federation of Rambling Clubs, was formed in London in 1905 and was heavily patronised by the peerage.[10]

Political Activism and Walking during Interwar Britain

During the 1930s, walking reached new levels of popularity as a pastime; in any weekend some ten thousand ramblers could be expected on the moors of the Peak District, while in the country at large there were over half a million ramblers.[11] A convergence of economic factors played their part in this boom in numbers; the 1920s saw a steady reduction in the working hours of the British worker occur in tandem with a rise in real wages and a decreasing cost of travel.[12] Come the early 1930s, a rise in unemployment meant that leisure time was more aplenty than ever and this was a catalyst for a surge in walking that was labelled by contemporaries ‘hiking craze’. [13] Accompanying this boom in numbers was an extremely high level of media coverage which, according to Ann Holt, was comparable to what would now be labelled as modern media hype.[14] Frank Trentmann, has suggested that the surge in walkers during the inter-war period made it “the numerically strongest part of the new romanticism in interwar Britain.”[15]

With these increasing numbers came increasingly strong demands for walkers rights. Access to Mountains bills, that would have legislated the public's 'right to roam' across some private land, were periodically presented to Parliament from 1884 to 1932 without success. Mass rallies and trespasses were held in support of this cause during this period, including an annual access to mountains demonstration at Winnats Pass and, most famously, a mass trespass on Kinder Scout in Derbyshire. However, the Mountain Access Bill that was passed in 1939 was opposed by many walkers, including the organisation The Ramblers, who felt that it did not sufficiently protect their rights, and it was eventually repealed.[16]

The effort to improve access led after World War II to the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949, and in 1951 to the creation of the first national park in the UK, the Peak District National Park.[17] The establishment of this and similar national parks helped to improve access for all outdoors enthusiasts.[18] The Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 considerably extended the right to roam in England and Wales.

Walking tour

A walking tour is an extended walk in the countryside, undertaken by an individual, or group for several days. Walking tours have their origin in the Romantic movement of the late 18th, early 19th-century.[19] It has some similarities with backpacking, trekking, and also tramping in New Zealand, though it need not take place in remote places. In the late 20th-century, with proliferation of official and unofficial long-distance walking routes, walkers now are more likely to follow a long-distance way, than to plan their own walking tour. Such tours are also organised by commercial companies, and can have a professional guide, or are self-guided; in these commercially organised tours, luggage is often transported between accommodation stops.

Access to the countryside

England and Wales

Rights of way

In England and Wales the public has a legally protected right to "pass and repass" (i.e. walk) on footpaths, bridleways and other routes which have the status of a public right of way. Footpaths typically pass over private land, but if they are public rights of way they are public highways with the same protection in law as other highways, such as trunk roads.[20] Public rights of way originated in common law, but are now regulated by the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000. These rights have occasionally resulted in conflicts between walkers and landowners. The rights and obligations of farmers who cultivate crops in fields crossed by public footpaths are now specified in the law. Walkers can also use permissive paths, where the public does not have a legal right to walk, but where the landowner has granted permission for them to walk.

Rights of way in London

Definitive maps of public rights of way have been compiled for all of England and Wales as a result of Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000, except the 12 Inner London boroughs[21] which, along with the City of London, were not covered by the Act.

To protect the existing rights of way in London the Ramblers launched their "Putting London on the Map" in 2010 with the aim of getting "the same legal protection for paths in the capital as already exists for footpaths elsewhere in England and Wales. Currently, legislation allows the Inner London boroughs to choose to produce definitive maps if they wish, but none do so".[22]

Right to roam

Walkers long campaigned for the right to roam, or access privately owned uncultivated land. In 1932 the mass trespass of Kinder Scout had a far-reaching impact.[23] The 1949 Countryside Act created the concept of designated open Country, where access agreements were negotiated with landowners. The Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 gave walkers a conditional right to access most areas of uncultivated land.

Scotland

Right to roam

In Scotland there is a traditional presumption of universal access to land. This was formally codified into Scots law under the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003, which grants everyone the right to be on most land and inland water for recreation, education, and going from place to place, providing they act responsibly.[2] The basis of access rights in Scotland is one of shared responsibilities, in that those exercising such rights have to act responsibly, whilst landowners and managers have a reciprocal responsibility to respect the interests of those who exercise their rights.[24] The Scottish Outdoor Access Code provides detailed guidance on these responsibilities.

Responsible access can be enjoyed over the majority of land in Scotland, including all uncultivated land such as hills, mountains, moorland, woods and forests. Access rights also apply to fields in which crops have not been sown or in which there are farm animals grazing; where crops are growing or have been sown access rights are restricted to the margins of those fields. Access rights do not apply to land on which there is a building, plant or machinery. Where that building is a house or other dwelling (e.g. a static caravan) the land surrounding it is also excluded in order to provide reasonable measures of privacy.[25] The issue of how much land surrounding a building is required to provide "reasonable measures of privacy" has been the main issue on which the courts have been asked to intervene. In Gloag v. Perth and Kinross Council the sheriff allowed about 5.7 hectares (14 acres) surrounding Kinfauns Castle, a property belonging to Ann Gloag, to be excluded from access rights. In Snowie v Stirling Council and the Ramblers’ Association the courts allowed about 5.3 hectares (13 acres) to be excluded, but refused permission for a wider area to be excluded and required the landowner to keep the driveway unlocked to allow access.[26][27]

Rights of way

In addition to the general right of access the public also have the right to use any defined route over which the public has been able to pass unhindered for at least 20 years. However, local authorities are not required to maintain and signpost public rights of way as they are in England and Wales.

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland has very few public rights of way and access to land in Northern Ireland is more restricted than other parts of the UK, so that in many areas walkers can only enjoy the countryside because of the goodwill and tolerance of landowners. Permission has been obtained from all landowners across whose land the Waymarked Ways and Ulster Way traverse. Much of Northern Ireland's public land is accessible, e.g. Water Service and Forest Service land, as is land owned and managed by organisations such as the National Trust and the Woodland Trust.[28]

Northern Ireland shares the same legal system as England, including concepts about the ownership of land and public rights of way, but it has its own court structure, system of precedents and specific access legislation.[29]

Long-distance footpaths

.jpg)

Long-distance paths are created by linking public footpaths, other rights of way, and sometimes permissive paths, to form a continuous walking route. They are usually waymarked and guidebooks are available for most long-distance paths. Paths are generally well signposted, although a map is also needed, and a compass may sometimes be needed on high moorland. There are usually places to camp on an extended trip, but accommodation of various kinds is available on many routes. However, occasionally paths are distant from settlements, so that camping is necessary. Water is not available on high downland paths, like The Ridgeway, though taps have been provided at some spots.

Fifteen paths in England and Wales have the status of National Trails, which attract government financial support. Twenty-nine paths in Scotland have the similar status of Scotland's Great Trails. The first long-distance path was the Pennine Way, which was proposed by Tom Stephenson in 1935, and finally opened in 1965. Other paths include South Downs Way and Offa's Dyke Path. Major guides to these long-distance footpaths in Britain are provided by HMSO for the Countryside Commission, one of the first being that for the Pennine Way by Tom Stephenson in the 1960s.

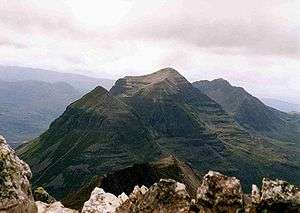

Hillwalking

Walks or hikes undertaken in upland country, moorland, and mountains, especially when they include climbing a summit are sometimes described as hillwalking or fellwalking in the United Kingdom. Though hillwalking can entail scrambling to reach a mountain summit, it is not mountaineering.[30][31] Fellwalking is a word used specifically to refer to hill or mountain walking in Northern England, including the Lake District, Lancashire, especially the Forest of Bowland, and the Yorkshire Dales, where fell is a dialect word for high, uncultivated land.

Popular locations for hillwalking include the Lake District, the Peak District, the Yorkshire Dales, Snowdonia, the Brecon Beacons and Black Mountains, Wales, Dartmoor and the Scottish Highlands. The mountains in Britain are modest in height, with Ben Nevis at 4,409 feet (1,344 m) the highest, but the unpredictably wide range of weather conditions, and often difficult terrain, can make walking in many areas challenging. Peak bagging provides a focus for the activities of many hillwalkers. The first of the many hill lists compiled for this purpose was the Munros – mountains in Scotland over 3,000 feet (910 m) – which remains one of the most popular.

The United Kingdom offers a wide variety of ascents, from gentle rolling lowland hills to some very exposed routes in the moorlands and mountains. The term climbing is used for the activity of tackling the more technically difficult ways of getting up hills involving rock climbing while hillwalking refers to relatively easier routes.

However, many hillwalkers become proficient in scrambling, an activity involving use of the hands for extra support on the crags. It is an ambiguous term that lies somewhere between walking and rock climbing, and many easy climbs are sometimes referred to as difficult scrambles. A distinction can be made by defining any ascent as a climb, when hands are used to hold body weight, rather than just for balance. While much of the enjoyment of scrambling depends on the freedom from technical apparatus, unroped scrambling in exposed situations is potentially one of the most dangerous of mountaineering activities, and most guidebooks advise carrying a rope, especially on harder scrambles, which may be used for security on exposed sections, to assist less confident members of the party, or to facilitate retreat in case of difficulty. Scramblers need to know their limits and to turn back before getting into difficulties. Many easy scrambles in good weather become serious climbs if the weather deteriorates. Black ice or verglas is a particular problem in cold weather, and mist or fog can disorientate scramblers very quickly.

Many of the world's mountaintops may be reached by walking or scrambling up their least steep side. In Great Britain ridge routes which involve some scrambling are especially popular, including Crib Goch on Snowdon, the north ridge of Tryfan, Striding Edge on Helvellyn and Sharp Edge on Blencathra in the Lake District, as well as numerous routes in Scotland such as the Aonach Eagach ridge in Glencoe. Many such routes include a "bad step" where the scrambling suddenly becomes much more serious.

In Britain, the term "mountaineering" tends to be reserved for technical climbing on mountains, or for serious domestic hillwalking, especially in winter, with additional equipment such as ice axe and crampons, or for routes requiring rock-climbing skills and a rope, such as the traverse of the Cuillin ridge, on the Scottish island of Skye. The British Mountaineering Council provides more information on this topic.[32]

Navigation and map-reading are essential hillwalking skills on high ground and mountains, due to the variability of British and Irish weather and the risk of rain, low cloud, fog or the onset of darkness. In some areas it is common for there to be no waymarked path to follow. In most areas walking boots are essential along with weatherproof clothing, spare warm clothes, and in mountainous areas a bivvy bag or bothy bag in case an accident forces a prolonged, and possibly overnight halt. Other important items carried by hillwalkers are: food and water, an emergency whistle, torch/flashlight (and spare batteries), and first aid kit. And, where reception permits, a fully charged mobile phone is recommended. Hillwalkers are also advised to let someone know their route and estimated time of return or arrival.

Guidebooks

W A Poucher (1891–1988) wrote several hillwalking guide books, in the 1960s, which describe, in detail, the various routes up specific mountains, along with the precautions needed and other practical information useful to walkers. The guides cover Wales, Peak District, Scotland, Isle of Skye and the Lake District. Even more detailed guides were written by Alfred Wainwright (1907–1991) but these are mainly restricted to the Lake District and environs. His main series of seven books was first published between 1955 and 1966. Both authors describe the major paths, their starting points and the peaks where they end, with important landmarks along each route. Neither are entirely comprehensive. More recently Mark Richards has written numerous walking guides, especially for the Lake District, for the publisher Cicerone, who are now the leading publisher of walking guides in the UK. The Scottish Mountaineering Club are, through the experience and knowledge of their members, the largest publishers of guidebooks to climbing and walking in Scotland.

Walking in London

Walking is a popular recreational activity in London, despite traffic congestion. There are many areas that provide space for interesting walks, including commons, parks, canals, and disused railway tracks. This includes Wimbledon Common, Hampstead Heath, the eight Royal Parks, Hampton Court Park, and Epping Forest. In recent years access to canals and rivers, including the Regents Canal, and the River Thames has been greatly improved, and as well a number of long-distance walking routes have been created that link green spaces.

The following are some of long-distance routes in London:

- Capital Ring a 75 miles (121 km) circular route with 15 sections and a radius of approximately 4–8 miles (6–13 km) from Charing Cross, mostly through the inner Outer London suburbs but also partly in Inner London. The route forms a complete circuit, crossing the River Thames twice and with a suggested starting point at Woolwich;

- London Outer Orbital Path ("Loop") a 150-mile (240 km) circular route with 24 sections mostly through Outer London suburbs. The "M25" for walkers, the path is broken because the Thames cannot be crossed between Purfleet and Erith;

- Jubilee Walkway a route through central London, originally called the Silver Jubilee Walkway, laid down in 1977 as part of the celebrations of the Silver Jubilee of Elizabeth II. The route takes in many of London's major attractions;

- Lea Valley Walk which starts outside Greater London but has around 12.5 miles (20 km) within its boundary. The route follows the River Lea and the Lee Navigation;

- The River Thames Path a National Trail, opened in 1996, following the length of the River Thames, starting outside London at its source near Kemble in Gloucestershire and ending at the Thames Barrier at Charlton. It is about 184 miles (296 km) long. More than 20 miles (32 km) are within London.

Challenge walks

Challenge walks are strenuous walks by a defined route to be completed in a specified time. Many are organised as annual events, with hundreds of participants. In May and June, with longer daylight hours, challenge walks may be 40 or more miles. A few are overnight events, covering distances up to 100 miles. Well-known challenge walks include the Lyke Wake Walk and the Three Peaks Challenge in Yorkshire, and the Three Towers Hike in Berkshire. See also Long Distance Walkers Association.

There are also some challenge walks aimed at children, young adults and youth groups such as the Chase Walk.

Walking for health

In the UK the health benefits of walking are widely recognised. In 1995 Dr William Bird, a general practitioner, started the concept of "health walks" for his patients—regular, brisk walks undertaken to improve an individual's health. This led to the formation of the Walking for Health Initiative (WfH, formerly known as 'Walking the way to Health' or WHI) by Natural England and the British Heart Foundation. WfH trains volunteers to lead free health walks from community venues such as libraries and GP surgeries. The scheme has trained more than 35,000 volunteers and there are more than 500 Walking for Health schemes across the UK, with thousands of people walking every week.[33] In 2008 the Ramblers launched its flagship Get Walking Keep Walking project, funded by the Big Lottery and Ramblers Holidays Charitable Trust.[34] Unlike regular health walks, the Get Walking Keep Walking model uses targeted outreach programmes based around a 12-week walking plan to encourage regular independent walking. In the same year, a new organisation, Walk England was formed, with aid from the National Lottery and the Department for Transport, to provide support to health, transport and environmental professionals who are working to encourage walking.[35]

Organisations

The government agency responsible for promoting access to the countryside in England is Natural England. In Wales the comparable body is the Countryside Council for Wales, and in Scotland Scottish Natural Heritage. The Ramblers (Britain's Walking Charity) promotes the interests of walkers in Great Britain and provides information for its members and others.[36] Local Ramblers volunteers organise hundreds of group-led walks every week, all across Britain. These are primarily for members; non-members are welcomed as guests for two or three walks.[37] The Get Walking Keep Walking project provides free led walks for residents in certain areas, information and resources to those new to walking.[34]

Among the organisations that promote the interest of walkers are: the Ramblers Association, the British Mountaineering Council, the Mountaineering Council of Scotland, The Online Fellwalking Club, and the Long Distance Walkers Association, which assists users of long-distance trails and challenge walkers. Organisations which provide overnight accommodation for walkers include the Youth Hostels Association in England and Wales, the Scottish Youth Hostels Association, and the Mountain Bothies Association.

See also

- Fastpacking

- List of mountains in Ireland

- Ten essentials (gear)

- List of mountains and hills of the United Kingdom

References

- "Page cannot be found - Ramblers". www.ramblers.org.uk.

- "Enjoy Scotland's Outdoors" (PDF). Scottish Government. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- "ramble | Search Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com.

- The Norton Anthology of English Literature, ed. M. H. Abrams, vol. 2 (7th edition) (2000), p. 9-10.

- Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust: A History of Walking. New York: Penguin Books, 2000, p.83, and note p.297.

- West. A Guide to the Lakes. p. 2.

- "Development of tourism in the Lake District National Park". Lake District UK. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- "Understanding the National Park – Viewing Stations". Lake District National Park Authority. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- "Sunday Tramps", National Portrait Gallery, London

- Stephenson, Tom (1989). Forbidden Land: The Struggle for Access to Mountain and Moorland. Manchester University Press. p. 78. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- Alun Howkins and John Lowerson, Trends in Leisure 1919-1939: A Review for the Joint Panel on Leisure and Recreation Research (London: Sports Council and Social Science Research Council, 1979), 49.

- Frank Trentmann, “Civilization and Its Discontents: English Neo-Romanticism and the Transformation of Anti-Modernism in Twentieth-Century Western Culture,” Journal of Contemporary History 29:4 (1994), 583-625, 586,

- Alun Howkins and John Lowerson, Trends in Leisure 1919-1939: A Review for the Joint Panel on Leisure and Recreation Research (London: Sports Council and Social Science Research Council, 1979), 48.

- Ann Holt, “Hikers and Ramblers: Surviving a Thirties Fashion,” The International Journal of the History of Sport 4 (1987): 56-67,

- Frank Trentmann, “Civilization and Its Discontents: English Neo-Romanticism and the Transformation of Anti-Modernism in Twentieth-Century Western Culture,” Journal of Contemporary History 29:4 (1994), 583-625, 585.

- "Page cannot be found - Ramblers". www.ramblers.org.uk.

- "Quarrying and mineral extraction in the Peak District National Park" (PDF). Peak District National Park Authority. 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- "Kinder Trespass. A history of rambling". Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust: A History of Walking. New York: Penguin Books, 2000, p.104.

- "Ramblers Association: Basics of Footpath Law".

- "Naturenet: Rights of Way Definitive Maps". naturenet.net.

- "Inner London Ramblers".

- "Kinder Mass Trespass 'should be taught in schools'". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- "About the Scottish Outdoor Access Code". Scottish Natural Heritage. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- "Scottish Outdoor Access Code" (PDF). Scottish Natural Heritage. 2005. pp. 7–13. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- "Summary of Scottish access and liability court cases" (PDF). Cairngorms Local Outdoor Access Forum. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- Carrell, Severin (14 June 2007). "Multimillionaire uses financial muscle to bar ramblers from woods". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 August 2008.

- "Access - Useful Info - Walk NI". www.walkni.com.

- A Guide to Public Rights of Way and Access to the Countryside: .

- Alex Messenger (4 April 1999). "BMC – Safety & Skills". British Mountaineering Council. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- "Mountaineering Ireland (Previously MCI)". Mountain Leader Training Northern Ireland. Mountaineering Ireland. 2009. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- "The British Mountaineering Council". www.thebmc.co.uk.

- "Walking & Hiking Information – Walking & hiking activities".

- Get Walking Keep Walking website

- "Welcome to Walk Unlimited". www.walkengland.org.uk.

- "Ramblers". www.ramblers.org.uk.

- "Page cannot be found - Ramblers". www.ramblers.org.uk.

External links

- Directory of Rambling Clubs in the UK

- Dog Walks Near Me (Countryside walks across the UK)

- Long Distance Walkers Association website

- Open Paths and Trails website

- Ramblers Association website

- Walking routes and planner