Feldspar

Feldspars (KAlSi3O8 – NaAlSi3O8 – CaAl2Si2O8) are a group of rock-forming tectosilicate minerals that make up about 41% of the Earth's continental crust by weight.[2][3]

Feldspars crystallize from magma as both intrusive and extrusive igneous rocks and are also present in many types of metamorphic rock.[4] Rock formed almost entirely of calcic plagioclase feldspar is known as anorthosite.[5] Feldspars are also found in many types of sedimentary rocks.[6]

Compositions

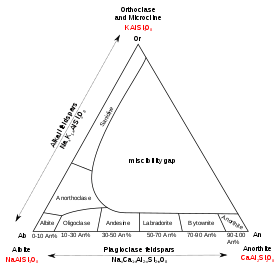

This group of minerals consists of tectosilicates, silicate minerals in which silicon ions are linked by shared oxygen ions to form a three-dimensional network. Compositions of major elements in common feldspars can be expressed in terms of three endmembers:

- potassium feldspar (K-spar) endmember KAlSi3O8,[7]

- albite endmember NaAlSi3O8,[7]

- anorthite endmember CaAl2Si2O8.[7]

Solid solutions between K-feldspar and albite are called alkali feldspar.[7] Solid solutions between albite and anorthite are called plagioclase,[7] or, more properly, plagioclase feldspar. Only limited solid solution occurs between K-feldspar and anorthite, and in the two other solid solutions, immiscibility occurs at temperatures common in the crust of the Earth. Albite is considered both a plagioclase and alkali feldspar.

Alkali feldspars

Alkali feldspars are grouped into two types: those containing potassium in combination with sodium, aluminum, or silicon; and those where potassium is replaced by barium. The first of these include:

- orthoclase (monoclinic)[8] KAlSi3O8,

- sanidine (monoclinic)[9] (K,Na)AlSi3O8,

- microcline (triclinic)[10] KAlSi3O8,

- anorthoclase (triclinic) (Na,K)AlSi3O8.

Potassium and sodium feldspars are not perfectly miscible in the melt at low temperatures, therefore intermediate compositions of the alkali feldspars occur only in higher temperature environments.[11] Sanidine is stable at the highest temperatures, and microcline at the lowest.[8][9] Perthite is a typical texture in alkali feldspar, due to exsolution of contrasting alkali feldspar compositions during cooling of an intermediate composition. The perthitic textures in the alkali feldspars of many granites can be seen with the naked eye.[12] Microperthitic textures in crystals are visible using a light microscope, whereas cryptoperthitic textures can be seen only with an electron microscope.

In addition, peristerite is the name given to feldspar containing approximately equal amounts of intergrown alkali feldspar and plagioclase.[13]

Barium feldspars

Barium feldspars are also considered alkali feldspars. Barium feldspars form as the result of the substitution of barium for potassium in the mineral structure.

The barium feldspars are monoclinic and include the following:

- celsian BaAl2Si2O8,[14]

- hyalophane (K,Ba)(Al,Si)4O8.[15]

Plagioclase feldspars

The plagioclase feldspars are triclinic. The plagioclase series follows (with percent anorthite in parentheses):

- albite (0 to 10) NaAlSi3O8,

- oligoclase (10 to 30) (Na,Ca)(Al,Si)AlSi2O8,

- andesine (30 to 50) NaAlSi3O8–CaAl2Si2O8,

- labradorite (50 to 70) (Ca,Na)Al(Al,Si)Si2O8,

- bytownite (70 to 90) (NaSi,CaAl)AlSi2O8,

- anorthite (90 to 100) CaAl2Si2O8.

Intermediate compositions of plagioclase feldspar also may exsolve to two feldspars of contrasting composition during cooling, but diffusion is much slower than in alkali feldspar, and the resulting two-feldspar intergrowths typically are too fine-grained to be visible with optical microscopes. The immiscibility gaps in the plagioclase solid solutions are complex compared to the gap in the alkali feldspars. The play of colors visible in some feldspar of labradorite composition is due to very fine-grained exsolution lamellae known as Bøggild intergrowth. The specific gravity in the plagioclase series increases from albite (2.62) to anorthite (2.72–2.75).

Etymology

The name feldspar derives from the German Feldspat, a compound of the words Feld ("field") and Spat ("flake"). Spat had long been used as the word for "a rock easily cleaved into flakes"; Feldspat was introduced in the 18th century as a more specific term, referring perhaps to its common occurrence in rocks found in fields (Urban Brückmann, 1783) or to its occurrence as "fields" within granite and other minerals (René-Just Haüy, 1804).[16] The change from Spat to -spar was influenced by the English word spar,[17] meaning a non-opaque mineral with good cleavage.[18] Feldspathic refers to materials that contain feldspar. The alternate spelling, felspar, has fallen out of use. The term 'felsic', meaning light colored minerals such as quartz and feldspars, is an acronymic word derived from feldspar and silica, unrelated to the redundant spelling 'felspar'.

Weathering

Chemical weathering of feldspars results in the formation of clay minerals[19] such as illite and kaolinite.

Production and uses

About 20 million tonnes of feldspar were produced in 2010, mostly by three countries: Italy (4.7 Mt), Turkey (4.5 Mt), and China (2 Mt).[20]

Feldspar is a common raw material used in glassmaking, ceramics, and to some extent as a filler and extender in paint, plastics, and rubber. In glassmaking, alumina from feldspar improves product hardness, durability, and resistance to chemical corrosion. In ceramics, the alkalis in feldspar (calcium oxide, potassium oxide, and sodium oxide) act as a flux, lowering the melting temperature of a mixture. Fluxes melt at an early stage in the firing process, forming a glassy matrix that bonds the other components of the system together. In the US, about 66% of feldspar is consumed in glassmaking, including glass containers and glass fiber. Ceramics (including electrical insulators, sanitaryware, pottery, tableware, and tile) and other uses, such as fillers, accounted for the remainder.[21]

Bon Ami, which had a mine near Little Switzerland, North Carolina, used feldspar as an abrasive in its cleaners. The Little Switzerland Business Association says the McKinney Mine was the largest feldspar mine in the world, and North Carolina was the largest producer. Feldspar had been discarded in the process of mining mica until William Dibbell sent a premium quality product to the Ohio company Golding and Sons around 1910.[22]

In earth sciences and archaeology, feldspars are used for potassium-argon dating, argon-argon dating, and luminescence dating.

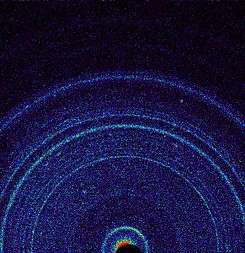

In October 2012, the Mars Curiosity rover analyzed a rock that turned out to have a high feldspar content.[23]

Images

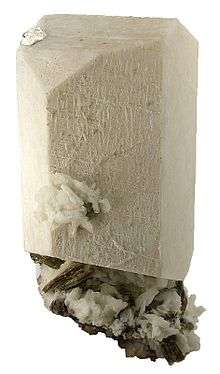

Specimen of rare plumbian (lead-rich) feldspar

Specimen of rare plumbian (lead-rich) feldspar Perched on crystallized, white feldspar is an upright 4 cm aquamarine crystal

Perched on crystallized, white feldspar is an upright 4 cm aquamarine crystal Feldspar and moonstone, from Sonora, Mexico

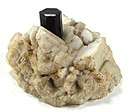

Feldspar and moonstone, from Sonora, Mexico Schorl crystal on a cluster of euhedral feldspar crystals

Schorl crystal on a cluster of euhedral feldspar crystals First X-ray view of Martian soil—feldspar, pyroxenes, olivine revealed (Curiosity rover at "Rocknest", October 17, 2012).[24]

First X-ray view of Martian soil—feldspar, pyroxenes, olivine revealed (Curiosity rover at "Rocknest", October 17, 2012).[24].jpg) Lunar ferrous anorthosite #60025 (plagioclase feldspar). Collected by Apollo 16 from the Lunar Highlands near Descartes Crater. This sample is currently on display at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

Lunar ferrous anorthosite #60025 (plagioclase feldspar). Collected by Apollo 16 from the Lunar Highlands near Descartes Crater. This sample is currently on display at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

See also

- List of minerals – A list of minerals for which there are articles on Wikipedia

- List of countries by feldspar production – Wikipedia list article

References

- "Feldspar". Gemology Online. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- Anderson, Robert S.; Anderson, Suzanne P. (2010). Geomorphology: The Mechanics and Chemistry of Landscapes. Cambridge University Press. p. 187. ISBN 9781139788700.

- Rudnick, R. L.; Gao, S. (2003). "Composition of the Continental Crust". In Holland, H. D.; Turekian, K. K. (eds.). Treatise on Geochemistry. Treatise on Geochemistry. 3. New York: Elsevier Science. pp. 1–64. Bibcode:2003TrGeo...3....1R. doi:10.1016/B0-08-043751-6/03016-4. ISBN 978-0-08-043751-4.

- "Metamorphic Rocks." Metamorphic Rocks Information Archived 2007-07-01 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on July 18, 2007

- Blatt, Harvey and Tracy, Robert J. (1996) Petrology, Freeman, 2nd ed., pp. 206–210 ISBN 0-7167-2438-3

- "Weathering and Sedimentary Rocks." Geology. Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on July 18, 2007.

- Feldspar. What is Feldspar? Industrial Minerals Association. Retrieved on July 18, 2007.

- "The Mineral Orthoclase". Feldspar Amethyst Galleries, Inc. Retrieved on February 8, 2008.

- "Sanidine Feldspar". Feldspar Amethyst Galleries, Inc. Retrieved on February 8, 2008.

- "Microcline Feldspar". Feldspar Amethyst Galleries, Inc. Retrieved on February 8, 2008.

- Klein, Cornelis and Cornelius S. Hurlbut, Jr. Handbook of Mineralogy, Wiley, pp. 446–49 (Fig. 11-95 ISBN 0-471-80580-7

- Ralph, Jolyon and Chou, Ida. "Perthite". Perthite Profile on mindat.org. Retrieved on February 8, 2008.

- Klein and Hurlbut Manual of Mineralogy 20th ed., pp. 449–50

- Celsian–orthoclase series on Mindat.org.

- Celsian–hyalophane series on Mindat.org.

- Hans Lüschen (1979), Die Namen der Steine. Das Mineralreich im Spiegel der Sprache (2nd ed.), Thun: Ott Verlag, p. 215, ISBN 3-7225-6265-1

- Harper, Douglas. "feldspar". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2008-02-08.

- "spar". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- Nelson, Stephen A. (Fall 2008). "Weathering & Clay Minerals". Professor's lecture notes (EENS 211, Mineralogy). Tulane University. Retrieved 2008-11-13.

- Feldspar, USGS Mineral Commodity Summaries 2011

- Apodaca, Lori E. Feldspar and nepheline syenite, USGS 2008 Minerals Yearbook

- Neufeld, Rob (4 August 2019). "Visiting Our Past: Feldspar mining and racial tensions". Asheville Citizen-Times. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- Nasa's Curiosity rover finds 'unusual rock'. (12 October 2012) BBC News.

- Brown, Dwayne (October 30, 2012). "NASA Rover's First Soil Studies Help Fingerprint Martian Minerals". NASA. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

Further reading

- Bonewitz, Ronald Louis (2005). Rock and Gem. New York: DK Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7566-3342-4.

External links