Fanno Creek

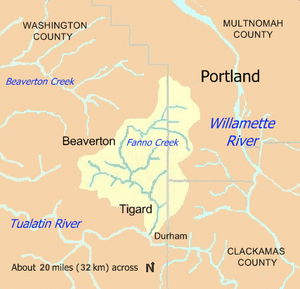

Fanno Creek is a 15-mile (24 km) tributary of the Tualatin River in the U.S. state of Oregon.[3] Part of the drainage basin of the Columbia River, its watershed covers about 32 square miles (83 km2) in Multnomah, Washington, and Clackamas counties, including about 7 square miles (18 km2) within the Portland city limits.

| Fanno Creek | |

|---|---|

Fanno Creek in Greenway Park, Beaverton | |

Fanno Creek watershed | |

Location of the mouth of Fanno Creek in Oregon | |

| Etymology | Augustus Fanno, early settler |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Oregon |

| County | Multnomah and Washington |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Tualatin Mountains (West Hills) |

| • location | Portland, Multnomah County, Oregon |

| • coordinates | 45°28′44″N 122°42′00″W[1] |

| • elevation | 478 ft (146 m)[2] |

| Mouth | Tualatin River |

• location | Durham, Washington County, Oregon |

• coordinates | 45°23′35″N 122°45′50″W[1] |

• elevation | 108 ft (33 m)[1] |

| Length | 15 mi (24 km)[3] |

| Basin size | 31.7 sq mi (82 km2)[3] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Durham, 1.13 miles (1.82 km) from mouth[4] |

| • average | 43.9 cu ft/s (1.24 m3/s)[4] |

| • minimum | 1 cu ft/s (0.028 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 1,670 cu ft/s (47 m3/s) |

From its headwaters in the Tualatin Mountains (West Hills) in southwest Portland, the creek flows generally west and south through the cities of Portland, Beaverton, Tigard and Durham, and unincorporated areas of Washington County. It enters the Tualatin River about 9 miles (14 km) above the Tualatin's confluence with the Willamette River at West Linn.

When settlers of European origin arrived, the Kalapuya lived in the area, having displaced the Multnomahs in pre-contact times. In 1847, the first settler of European descent, Augustus Fanno, for whom the creek is named, established an onion farm in what became Beaverton. Fanno Farmhouse, the restored family home, is a Century Farm on the National Register of Historic Places and is one of 16 urban parks in a narrow corridor along the creek.

Although heavily polluted, the creek supports aquatic life, including coastal cutthroat trout (leopard spotted) in its upper reaches. Watershed councils such as the Fans of Fanno Creek and government agencies have worked to limit pollution and to restore native vegetation in riparian zones.

Course

Fanno Creek arises at an elevation of 478 feet (146 m) above sea level and falls 370 feet (110 m) between source and mouth to an elevation of 108 feet (33 m).[2][1] The main stem begins at about river mile (RM) 15 or river kilometer (RK) 24 in the Hillsdale neighborhood of southwest Portland, in Multnomah County. The creek flows west along the north side of Oregon Route 10 (the Beaverton–Hillsdale Highway), passing Albert Kelly Park and receiving Ivey Creek and Bridlemile Creek on the right before reaching the United States Geological Survey (USGS) stream gauge at Southwest 56th Avenue 11.9 miles (19.2 km) from the mouth. Shortly thereafter and in quick succession, it enters Washington County and the unincorporated community of Raleigh Hills, crosses under Route 10, and receives Sylvan Creek on the right. Here the stream turns south, passing through Bauman Park, where Vermont Creek enters on the left about 10 miles (16 km) from the mouth, and then southwest to flow through the Portland Golf Club and Vista Brook Park, where Woods Creek enters on the left. From here it flows west again for about 1 mile (1.6 km), passing through Fanno Creek Trail Park and entering Beaverton about 8 miles (13 km) from the mouth before turning sharply south and flowing under Oregon Route 217 (Beaverton–Tigard Highway).[5][6][7][8]

Fanno Creek then flows roughly parallel to Route 217 for about 2 miles (3 km) through Fanno Creek Park and Greenway Park. Near the southern end of Greenway Park, the creek passes under Oregon Route 210 (Scholls Ferry Road), and enters Tigard about 5 miles (8 km) from the mouth. In quick succession, Hiteon Creek enters on the right, Ash Creek on the left, and Summer Creek on the right before the creek reaches Woodard Park, goes under Oregon Route 99W (Southwest Pacific Highway), and flows through Fanno Park and Bonita Park as well as residential neighborhoods. Between the two parks, Red Rock Creek enters on the left about 2.5 miles (4.0 km) from the mouth. Slightly downstream of Bonita Park, Ball Creek enters on the left. Fanno Creek then enters Durham, passes a USGS gauging station 1.13 miles (1.82 km) from the mouth, flows through Durham City Park, and empties into the Tualatin River 9.3 miles (15.0 km) from its confluence with the Willamette River.[5][6][7][9]

Discharge

The USGS monitors the flow of Fanno Creek at two stations, one in Durham, 1.13 miles (1.82 km) from the mouth, and the other in Portland, 11.9 miles (19.2 km) from the mouth. The average flow of the creek at the Durham station is 43.9 cubic feet per second (1.24 m3/s). This is from a drainage area of 31.5 square miles (81.6 km2), more than 99 percent of the total Fanno Creek watershed. The maximum flow recorded there was 1,670 cubic feet per second (47 m3/s) on December 3, 2007, and the minimum flow was 1 cubic foot per second (0.03 m3/s) on September 13, 2001, and September 15, 2009.[4] At the Portland station, the average flow is 3.15 cubic feet per second (0.09 m3/s). This is from a drainage area of 2.37 square miles (6.1 km2) or about 7 percent of the total Fanno Creek watershed. The maximum flow recorded there was 733 cubic feet per second (21 m3/s) on February 8, 1996, and the minimum flow was 0.01 cubic feet per second (0.0003 m3/s) on September 4, 2001.[8]

Watershed

Draining 31.7 square miles (82.1 km2),[3] Fanno Creek receives water from Portland's West Hills, Sexton Mountain in Beaverton, and Bull Mountain near Tigard. Nearly all of the watershed is urban.[10] About 7 square miles (18 km2), roughly 22 percent of the total, lies inside the Portland city limits.[3] The highest elevation in the watershed is 1,060 feet (320 m) at Council Crest in the West Hills.[11] The peak elevation on Sexton Mountain is 476 feet (145 m),[12] while Bull Mountain rises to 715 feet (218 m).[13] About 117 miles (188 km) of streams flow through the watershed, including Ash Creek, Summer Creek, and 12 smaller tributaries.[11] A small part of the drainage basin lies in the city of Lake Oswego in Clackamas County, near the headwaters of Ball Creek, a Fanno Creek tributary.[14]

The slopes at the headwaters of Fanno Creek consist mainly of Columbia River Basalt exposed in ravines but otherwise covered by up to 25 feet (8 m) of wind-deposited silt. Silts and clays are the most common watershed soils, and significant erosion is common.[11] About 50 inches (1,300 mm) of precipitation, almost all of which is rain and about half of which arrives in November, December, and January, falls on the watershed each year. Although significant flooding occurred in 1977, the watershed has not experienced a 100-year flood since the area became urban.[11]

Small watersheds adjacent to the Fanno Creek watershed include those of minor tributaries of the Willamette or Tualatin rivers. Tryon Creek, Balch Creek, and other small streams east of Fanno Creek flow down the eastern flank of the West Hills into the Willamette. To the northwest, Hall Creek, Cedar Mill Creek, and Bronson Creek flow into Beaverton Creek, a tributary of Rock Creek, which empties into the Tualatin River at the larger stream's RM 38.4 (RK 61.8), about 29 miles (47 km) upriver from the mouth of Fanno Creek.[9][15]

Annual report card

In 2015, Portland's Bureau of Environmental Services (BES) began issuing annual "report cards" for watersheds or fractions thereof that lie within the city.[16][17] BES assigns grades for each of four categories: hydrology, water quality, habitat, and fish and wildlife. Hydrology grades depend on the amount of pavement and other impervious surfaces in the watershed and the degree to which its streams flow freely, not dammed or diverted. Water-quality grades are based on measurements of dissolved oxygen, E-coli bacteria, temperature, suspended solids, and substances such as mercury and phosphorus. Habitat ranking depends on the condition of stream banks and floodplains, riparian zones, tree canopies, and other variables. The fish and wildlife assessment includes birds, fish, and macroinvertebrates.[18] In 2015, the BES grades for the Fanno Creek watershed fraction within Portland are hydrology, C; water quality, C+; habitat, B−, and fish and wildlife, D−.[19]

History

The previous people of the Fanno Creek watershed were the Atfalati or Tualaty tribe of the Kalapuya, said to have displaced even earlier inhabitants, the Multnomahs, prior to European contact.[21] The valleys of the Willamette River and its major tributaries such as the Tualatin River consisted of open grassland maintained by annual burning, with scattered groves of trees along the rivers and creeks.[22] The Kalapuya moved from place to place in good weather to fish, to hunt small animals, birds, waterfowl, deer, and elk, and to gather nuts, seeds, roots, and berries. Important foods included camas and wapato.[22] In addition to fishing for eels, suckers, and trout, the Atfalati traded for salmon from Chinookan tribes near Willamette Falls.[22] During the winter, the Kalapuya lived in longhouses in settled villages. Their population was greatly reduced after contact in the late 18th century with Europeans, who carried malaria, smallpox, measles, and other diseases.[23] Added pressure came from white settlers who seized and fenced native land, regarded it as private property, and sometimes punished natives for trespassing.[22] Of the original population of 1,000 to 2,000 Atfalati reported in 1780, only 65 remained in 1851.[22] In 1855, the U.S. government sent the survivors to the Grande Ronde reservation further west.[22]

Fanno Creek is named after Augustus Fanno, the first European American settler along the creek. In 1847, he started an onion farm on a 640-acre (260 ha) donation land claim in what later became part of Beaverton.[11] Other 19th century newcomers along the creek engaged mainly in logging, farming, and dairy farming until the Southern Pacific Railroad and the Oregon Electric Railway lines made the watershed more accessible for urban development around the turn of the 20th century. The Oregon Electric, a 49-mile (79 km) system built between 1903 and 1915, ran between downtown Portland and Garden Home in the Fanno Creek watershed, where it split into branches leading to Salem and Forest Grove.[11] The Southern Pacific began running electric passenger trains, known as the Red Electric, in the watershed in 1914.[24] The company that eventually became Portland General Electric installed electric service in the area, and by 1915 the population of the upper Fanno Creek neighborhoods of Multnomah, Maplewood, Hillsdale, and West Portland Park had grown to 2,000.[11]

Passenger service on the Red Electric line ended in 1929,[11] and the Oregon Electric Railway ceased passenger operations in 1933.[25] Private autos largely replaced interurban rail service. Oregon Highway 217 between Durham and Beaverton, and Oregon Highway 10 between Beaverton and Portland, follow the creek. Although passenger rail ceased for nearly 80 years, freight trains continued to use the tracks. In 2009, a new rail passenger service began along a former Oregon Electric line owned by Portland and Western Railroad in Washington County.[25] The Westside Express Service (WES) runs 14.7 miles (23.7 km) between Beaverton on the north and Wilsonville on the south.[25] The middle stretch of this run lies close to the lower 8 miles (13 km) of Fanno Creek between Beaverton and Durham.[15] WES is the first modern commuter rail in Oregon and one of the few suburb-to-suburb commuter rail lines in the United States.[25] At the northern end of the line, WES connects to the MAX Blue Line, an east-west light rail line linking Hillsboro and Gresham via Portland and the MAX Red Line, with connections to Portland International Airport.

The highways and railroads serve a population that increased most dramatically in the second half of the 20th century. When Beaverton was incorporated as a city in 1893, it had a population of 400.[26] By 2010, the number had soared to 94,000, although not all of them lived in the watershed.[27] Tigard, which did not exist as a city until 1961, grew to 49,000 by the year 2013,[28] all in the watershed.[29] Fanno Creek, which had few people living near it until 1850, "is surrounded by the most populous region in Oregon".[29]

Pollution

Although the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) rated the average water quality of Fanno Creek as "very poor"[30] between 1986 and 1995, it also noted steady improvement over that span. Historically, Fanno Creek has been polluted by urban and industrial sources, small sewage treatment plants, ineffective septic systems, farming and grazing operations, and illegal dumping. Health and environmental concerns led to the closing of substandard wastewater treatment plants in the 1970s, and urban development reduced the number of farms and farm animals along the creek. A ban in 1991 on phosphate detergents, increased connection to municipal sewers, stormwater management, and greater public awareness helped to reduce urban pollution not coming from point sources, and water quality improved.[30]

DEQ monitors Fanno Creek at Bonita Road in Tigard, at about 2 miles (3 km) from the mouth. On the Oregon Water Quality Index (OWQI) used by DEQ, water quality scores can vary from 10 (worst) to 100 (ideal). The average for Fanno Creek between 1986 and 1995 was 55 but steadily improved to 65, or "poor",[30] by the end of the period. By comparison, the average in the nearby Willamette River at the Hawthorne Bridge in downtown Portland was 74 during the same years.[30] Measurements of water quality at the Tigard site during the years covered by the DEQ report showed high concentrations of phosphates, fecal coliform bacteria, and suspended solids, and a high biochemical oxygen demand. Moderately high concentrations of ammonia and nitrate nitrogen occurred during high flows during fall, winter, and spring. High temperatures and low dissolved oxygen concentration in the summer were evidence of eutrophication.[30]

The high fraction of impervious surfaces in the watershed makes it difficult to improve water quality in the creek. The Portland Bureau of Environmental Services estimates that one-third of the surface area of the watershed that lies within its jurisdiction is impervious.[31] All of the roughly 12 square miles (31 km2) of the surface of Tigard, much of it impervious, drains into Fanno Creek.[29] The watershed watch coordinator for Tualatin Riverkeepers, a volunteer group, was quoted in a July 2008 newspaper article saying that "the biggest impact to Fanno Creek is the impervious area".[29] To slow run-off, reduce erosion, and keep pollutants out of streams, watershed councils, neighborhood groups, and government agencies have been planting native species of vegetation at selected sites throughout the watershed.[29]

Biology

Fish and wildlife

About 100 bird species, several kinds of mammals, and a few fish species live in the watershed. Mammals commonly seen include beaver, raccoon, opossum, spotted skunk, Douglas squirrel, and Townsend's chipmunk; black-tail deer and coyotes are more rare. Fanno Creek supports non-migrating coastal cutthroat trout that spawn in the fast-flowing, gravel-bottomed headwaters and grow to as long as 14 inches (36 cm). Other fish species found in the creek include sculpins, mosquitofish and eel.[11]

Beavers, rodents weighing up to 60 pounds (27 kg), have sometimes caused problems along Fanno Creek. In 2014 and 2015, a growing population of beavers gnawed down trees and dammed the creek in Greenway Park in Beaverton. Rising waters have covered one of the side trails in the park, which has been gated and closed. During heavy rains, water from the beaver pond sometimes covers the main trail. Park officials are considering a variety of options, including re-routing the trails, building a boardwalk over the water, or removing the beaver dams.[32]

Vegetation

The creek begins in the Coast Range ecoregion designated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and flows thereafter through the Willamette Valley ecoregion.[33] The narrow riparian corridors along streams in the watershed commonly include native species such as western redcedar, Douglas fir, vine maple, and sword fern as well as invasive species like English ivy.[3] Many red alder and big leaf maple grow in the watershed, and shrubs include red huckleberry, Oregon-grape, elderberry, wood rose, and salmonberry.[11] A restoration project in Tigard along the main stem has removed invasive plants such as reed canary grass and Himalayan blackberry and replaced them with native species.[34] A project in Beaverton is replacing turf and degraded habitat along the creek with native shrubs and trees such as Oregon white oak.[35]

The Tualatin Riverkeepers, a nonprofit watershed council based in Tigard; Clean Water Services, a public utility that protects water resources in the Tualatin River watershed, and the Tualatin Hills Park & Recreation District (THPRD) have formed the Tualatin Basin Invasive Species Working Group to identify and eradicate invasive plants that displace native plants, cause erosion, and diminish water quality. The five plants considered most threatening are Japanese knotweed, meadow knapweed, giant hogweed, garlic mustard and purple loosestrife. The Oregon Department of Agriculture and the city of Tigard are working to eradicate giant hogweed from lower Fanno Creek.[36]

Parks

Fanno Creek passes through or near 16 parks in several jurisdictions. Portland Parks & Recreation manages three: Hillsdale Park, 5 acres (2.0 ha) with picnic tables and a dog park near the headwaters;[37] Albert Kelly Park, 12 acres (4.9 ha) with unpaved paths, picnic tables, play areas, and Wi-Fi north of the creek about 14 miles (23 km) from the mouth,[38] and the Fanno Creek Natural Area, 7 acres (2.8 ha) north of the creek about 12 miles (19 km) from the mouth.[39]

The Tualatin Hills Park & Recreation District (THPRD) manages seven Fanno Creek parks in Beaverton and unincorporated Washington County. The district, tax-supported and governed by an elected board, is the largest special park and recreation district in Oregon.[40] The seven include Bauman Park, about 8 acres (3.2 ha) at about 10 miles (16 km) from the mouth. Slightly downstream from Bauman Park are Vista Brook Park, about 4 acres (1.6 ha) with trails including one that is accessible to people with physical handicaps, a playground, and courts for basketball and tennis, and Fanno Creek Trail, about 2 acres (0.8 ha), with picnic tables and trails.[41] Other THPRD parks lie along Fanno Creek from roughly 7 miles (11 km) to roughly 5 miles (8 km) from the mouth. These are Fanno Creek Park, about 21 acres (8.5 ha), with trails including one accessible to people with handicaps; Fanno Farmhouse, about 1 acre (0.4 ha) with an accessible trail and picnic tables as well as the Fanno family home, restored by THPRD and listed on the National Register of Historic Places;[20] Greenway Park, about 87 acres (35 ha) with trails including an accessible trail, picnic tables, a playground, and sports fields, and Koll Center Wetlands, about 13 acres (5.3 ha) with wildlife.[41]

The five Fanno Creek parks managed by the city of Tigard include Englewood Park, 15 acres (6.1 ha) with play structures and trails, including a segment of the Fanno Creek Trail;[42] Woodard Park, 15 acres (6.1 ha) of big trees, trails, and play structures;[43] Bonita Park, 3.5 acres (1.4 ha) including a playground and picnic areas;[44] Dirksen Nature Park, 48 acres (19 ha) of forest, wetlands, and open space,[45] and Fanno Creek Park, a 30-acre (12 ha) natural area in downtown Tigard.[46] About 20 percent of the small city of Durham is parkland. Surrounded by the larger cities of Tigard and Tualatin, the city covers 265 acres (107 ha) occupied by about 1,400 people. Durham City Park, at the confluence of Fanno Creek and the Tualatin River, consists of 46 acres (19 ha) of heavily wooded floodplain with paved trails, children's play areas, and a picnic shelter.[47]

Sections of trail along the main stem of Fanno Creek form part of a planned 15-mile (24 km) Fanno Creek Greenway Trail linking Willamette Park on the Willamette River in southwest Portland to the confluence of the creek with the Tualatin River in Durham. The trail, for pedestrians and bicyclists, is accessible to people with disabilities. Several unfinished segments remained as of 2013.[48][49]

See also

Notes and references

- "Fanno Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. November 28, 1980. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- Source elevation derived from Google Earth search using GNIS source coordinates.

- "Fanno Creek Watershed". Bureau of Environmental Services, City of Portland. 2008. Retrieved May 5, 2008.

- "Water-Data Report 2011: USGS 14206950 Fanno Creek at Durham, OR" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- City Street Map: Portland, Gresham (Map) (2007 ed.). G.M. Johnson and Associates. ISBN 978-1-897152-94-2.

- Streets of Portland (Map) (2006 ed.). Rand McNally. ISBN 0-528-86776-8.

- Oregon Atlas & Gazetteer (Map) (1991 ed.). DeLorme Mapping. § 60–61. ISBN 0-89933-235-8.

- "Water-Data Report: 14206900 Fanno Creek at 56th Avenue at Portland, OR" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- "Tour of the Watershed" (PDF). Tualatin Riverkeepers. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 19, 2014. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- "Major Issues and Findings in the Willamette Basin: Pesticides and Volatile Organic Compounds". Water Quality in the Willamette Basin, Oregon, 1991–95. United States Geological Survey. 1998. Archived from the original on March 30, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2008.

- Alta Planning + Design (2003). "Fanno Creek Greenway Trail Action Plan" (PDF). Metro. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 10, 2015. Retrieved May 13, 2008.

- "Sexton Mountain". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. November 28, 1980. Retrieved May 14, 2008.

- "Bull Mountain". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. November 28, 1980. Retrieved May 14, 2008.

- Tualatin Riverkeepers (2002). Exploring the Tualatin River Basin. Corvallis, Oregon: Oregon State University Press. p. 105. ISBN 0-87071-540-2.

- Local: Beaverton/Hillsboro, McMinnville/Newberg (Map) (2003 ed.). Rand McNally. ISBN 0-528-99834-X.

- Bureau of Environmental Services (2015). "About Watershed Report Cards". City of Portland. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- Bureau of Environmental Services (2015). "Report Cards". City of Portland. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- Bureau of Environmental Services (2015). "What We Measure". City of Portland. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- Bureau of Environmental Services (2015). "Fanno Creek Report Card". City of Portland. Archived from the original on August 14, 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- "Oregon National Register List" (PDF). Oregon Parks and Recreation Department. October 19, 2009. p. 46. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- Ruby, Robert H.; Brown, John A. (1992). A Guide to the Indian Tribes of the Pacific Northwest (Revised ed.). Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 10, 142. ISBN 0-8061-2479-2.

- Tualatin Riverkeepers (2002). Exploring the Tualatin River Basin. Corvallis, Oregon: Oregon State University Press. pp. 21–23. ISBN 0-87071-540-2.

- Robbins, William G. (2002). "Native Cultures and the Coming of Other People: Old World Contagions". The Oregon History Project. Oregon Historical Society. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- Culp, Edwin D. (1978) [1972]. Stations West: The Story of the Oregon Railways. New York: Bonanza Books. p. 230. OCLC 4751643.

- "Partnership Brings Oregon's First Commuter Rail Line Closer to Reality" (PDF). Tri-Met. May 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2009. Retrieved August 15, 2008.

- "Beaverton History". City of Beaverton. Archived from the original on August 10, 2015. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- "About Beaverton". City of Beaverton. 2015. Archived from the original on August 10, 2015. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- "Oregon Bluebook: Tigard". Oregon State Archives. 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2008.

- Swan, Darryl (July 17, 2008). "Reversing Toxic Toll on Fanno Creek". Portland Tribune. Pamplin Media Group.

- Wade, Curtis. "Tualatin Subbasin". Oregon Water Quality Index Report for Lower Willamette, Sandy, and Lower Columbia Basins: Water Years 1986–1995. Oregon Department of Environmental Quality. Archived from the original on April 30, 2015. Retrieved May 17, 2008.

- "Hydrology and Infrastructure". Bureau of Environmental Services, City of Portland. 2011. Archived from the original on November 12, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- Owen, Wendy (March 4, 2015). "Man vs. Beast: Beavers Blossom at Greenway Park, Dams Flood Fanno Creek Trail". The Oregonian. Oregon Live. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- Thorson, T.D.; Bryce, S.A.; Lammers, D.A.; et al. (2003). "Ecoregions of Oregon (color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photographs)" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved November 18, 2019 – via Oregon State University.

- "Grant Received for Fanno Creek Park Enhancement Plan". City of Tigard. 2003. Archived from the original on April 26, 2005. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- "Greenway Habitat Enhancement Plan" (PDF). Tualatin Hills Park & Recreation District. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 30, 2011. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- "Tualatin Watershed Weed Watch". Tualatin Riverkeepers. Archived from the original on July 23, 2008. Retrieved May 19, 2008.

- Portland Parks and Recreation Department (2008). "Hillsdale Park". City of Portland. Retrieved May 5, 2008.

- Portland Parks and Recreation Department (2008). "Albert Kelly Park". City of Portland. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- Portland Parks and Recreation Department (2008). "Fanno Creek Natural Area". City of Portland. Retrieved May 5, 2008.

- "History of THPRD". Tualatin Hills Park and Recreation District. 2005. Archived from the original on August 14, 2015. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- "Parks and Trails: Locate Park or Trail". Tualatin Hills Park and Recreation District. 2008. Retrieved December 6, 2009.

- "Englewood Park". City of Tigard. Archived from the original on August 14, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- "Woodard Park". City of Tigard. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- "Bonita Park". City of Tigard. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- "Dirksen Nature Park". City of Tigard. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- "Fanno Creek Park". City of Tigard. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- "City of Durham, Oregon, Comprehensive Park and Recreation Plan". League of Oregon Cities. December 20, 2005. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- "Fanno Creek Greenway Trail". The Intertwine Alliance. 2013. Archived from the original on March 18, 2016. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- "Fanno Creek Greenway Trail". Metro. 2003. Archived from the original on August 10, 2015. Retrieved May 5, 2008.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fanno Creek. |

.jpg)