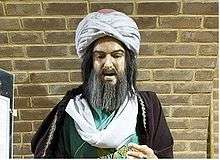

Fairuzabadi

Fairūzābādī (Persian: فیروزآبادی), variants: el-Fīrūz Abādī or al-Fayrūzabādī (Arabic: الفيروزآبادي) (1329–1414) was a lexicographer and was the compiler of al-Qamous (القاموس), a comprehensive and, for nearly five centuries, one of the most widely used Arabic dictionaries.[1]

Name

He was Abū al-Ṭāhir Majīd al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn Ya'qūb ibn Muḥammad ibn Ibrāhīm al-Shīrāzī al-Fīrūzābādī (أبو طاهر مجيد الدين محمد بن يعقوب بن محمد بن إبراهيم الشيرازي الفيروزآبادي), known simply as Muḥammad ibn Ya'qūb al-Fīrūzābādī (محمد بن يعقوب الفيروزآبادي).[2] His nisbas "al-Shīrāzī" and "al-Fīrūzābādī" refer to the cities of Shiraz and Firuzabad in Fars, Persia, respectively.

Life

Fairūzābādī was born in Fars, Persia, and educated in Shiraz, Wasit, Baghdad and Damascus. He spent ten years in Jerusalem before travelling in Western Asia and Egypt,[1] and settling in 1368, in Mecca for almost three decades. From Mecca he visited Delhi in the 1380s. He left Mecca in the mid-1390s and returned to Baghdad, then Shiraz (where he was received by Timur) and finally travelled on to Ta'izz[1] in Yemen. In 1395, he was appointed chief qadi (judge) of Yemen[1] by Al-Ashraf Umar II, who had summoned him from India a few years before to teach in his capital. Al-Ashraf's marriage to a daughter of Fairūzābādī added to Fairūzābādī's prestige and power in the royal court.[3] In his latter years, Fairūzābādī converted his house at Mecca, and appointed three teachers, to a school of Maliki law.[1]

Sufism and relations with Ibn Arabi

Fairūzābādī composed several poems lauding Ibn Arabi for his writings, including the وما علي إن قلت معتقدي دع الجهول يظن العدل عدوانا. Ibn Arabi's works inspired Fairūzābādī's intense interest in Sufism.

Selected Works

- Al-Qamus al-Muhit (القاموس المحيط) ("The Encompassing Dictionary"); his principal literary legacy is this voluminous dictionary, which amalgamates and supplements two great dictionaries; Al-Muhkam by Ibn Sida (d. 1066) and Al-ʿUbab (العباب الزاخر واللباب الفاخر) by al-Saghānī (d. 1252).[2][4] Al-Saghānī's dictionary had itself supplemented the seminal medieval Arabic dictionary of Al-Jawharī (d. ca. 1008), titled al-Sihah. Fairūzābādī also produced a concise simplified edition using a terse notation system and omitting grammatical examples of usage and some rarer definitions.[4] The larger-print-two-volume concise dictionary proved much more popular than the vast Lisan al-Arab dictionary of Ibn Manzur (d. 1312) with its numerous quotations and usage examples.

- Al-Bulghah fī tārīkh a'immat al-lughah (البلغة في تراجم أئمة النحو واللغة) (Damascus 1972, in Arabic).[5]

References

- Thatcher, Griffithes Wheeler (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 133.

- The Biographical Encyclopedia of Islamic Philosophy, edited by Oliver Leaman, year 2006, biographical entry for Al-Firuzabadi.

- Introduction of Bassair Dhawi Tamyeez

- Arabic Lexicography: Its History, and Its Place in the General History of Lexicography, by John Haywood, year 1965, pages 83 - 88.

- Fīrūzābādī, Muḥammad ibn Yaʻqūb (2000) [1972]. Bulgha fi ta’rīkh a’immat al-lugha (in Arabic). Dimashq: Wizārat al-Thaqāfah; Dār Sa’d al-Dīn. p. 362.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Arabic Lexicography: Its History, and Its Place in the General History of Lexicography, by John Haywood, year 1965

- Baheth.info has a searchable copy of Fairuzabadi's al-Qāmūs al-Muḥīṭ dictionary