Eynsford Castle

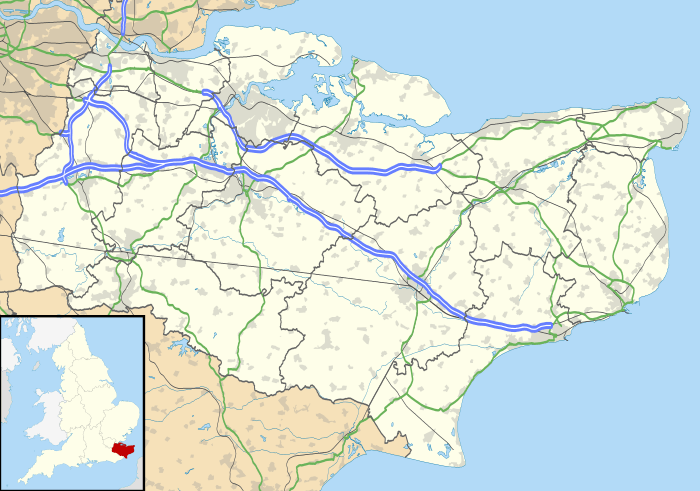

Eynsford Castle is a ruined medieval fortification in Eynsford, Kent. Built on the site of an earlier Anglo-Saxon stone burh, the castle was constructed by William de Enysford, probably between 1085 and 1087, to protect the lands of Lanfranc, the Archbishop of Canterbury, from Odo, the Bishop of Bayeux. It comprised an inner and an outer bailey, the former protected by a stone curtain wall. In 1130 the defences were improved, and a large stone hall built in the inner bailey. The de Enysford family held the castle until their male line died out in 1261, when it was divided equally between the Heringaud and de Criol families. A royal judge, William Inge, purchased half of the castle in 1307, and arguments ensued between him and his co-owner, Nicholas de Criol, who ransacked Eynsford in 1312. The castle was never reoccupied and fell into ruins, and in the 18th century it was used to hold hunting kennels and stables. The ruins began to be restored after 1897, work intensifying after 1948 when the Ministry of Works took over the running of the castle. In the 21st century, Eynsford Castle is managed by English Heritage and is open to visitors.

| Eynsford Castle | |

|---|---|

| Kent, England | |

_(18373797302)_(2).jpg) Entrance to Eynsford Castle | |

Eynsford Castle | |

| Coordinates | 51.370556°N 0.213333°E |

| Site information | |

| Owner | English Heritage |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Site history | |

| Materials | Flint stone |

History

10th–11th centuries

Eynsford Castle was built on the site of a former Anglo-Saxon manor.[1] The manor of Eynsford lay on a strategic point along the River Darent, overlooking a crossing point, and in 970 it was acquired by Christ Church, Canterbury.[2]

In the early 11th century, a stone building was then built in the manor on top of an artificial terrace, and it is possible that there may have been earlier stone buildings constructed on the same site.[3] The building was surrounded by a ditch and possibly a rampart, each approximately 5 metres (16 ft) wide and up to 3 metres (9.8 ft) deep and high respectively.[4] It is uncertain how far the outer defences reached; they may have traced the shape of the later castle, including a late-Anglo-Saxon cemetery located to the south-east.[4] The complex formed a secure aristocratic residence called a burh and the use of stone, rather than timber, in a secular building such as this was very unusual for the period.[5] Like some other burhs, it may have had an entrance tower called a burh-geat, symbolising the status of the owner.[6]

After the Norman invasion of 1066, Odo, the Bishop of Bayeux and the new Earl of Kent, probably acquired the manor, which had by this time been lost by its former owners in Canterbury.[7] The burh appears to have continued in use, either because the manor continued to be managed in the same way as before, or because the occupation of the former elite site demonstrated the Normans' power over the local community.[8] Odo's lands and those of the Archbishop of Canterbury bordered each other, and Eynsford fell within an area mainly controlled by Canterbury.[2] The Italian monk Lanfranc became the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1070, and set about attempting to recover the manor, probably finally doing so around 1082, when Odo was arrested by King William.[7] Lanfranc assigned a knight called Ralph, probably a lay retainer from Normandy, to run the estate, and appointed Ralph's son, William de Enysford, to the role on his father's death.[9]

Lanfranc remained concerned about the threat posed by Odo, and authorised William to improve the defences at Eynsford.[1] The work was probably carried out between 1085 and 1087, and enclosed the former burh with a stone curtain wall to form a castle.[10]

12th–14th centuries

_(17829035333).jpg)

William de Enysford's family continued to hold Eynsford Castle on behalf of the archbishop until 1261, through six descendants, all named William and therefore distinguished for convenience as William de Eynsford II through to VII by historians.[11] Around 1130, a new hall was built in the castle, superseding the older, by now abandoned Anglo-Saxon buildings, and the defences were strengthened with a new gate house and by raising the height of the curtain wall.[12] William I retired to become a monk in the 1130s, and his son William II had passed control of the castle to William III by the late 1140s.[13] William III became embroiled in the dispute between Henry II and the then Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, during the 1160s.[11] Despite being an ally of Becket, William argued with him over the appointment of a priest to Eynsford's church and was excommunicated for a period as a consequence.[11]

William IV died soon after inheriting the castle, but William V, who came of age in 1200, was increasingly involved in wider baronial politics, including serving in Ireland with King John, and taking part in the First Barons' War.[14] He sided with the rebels against John during the civil war and was captured at Rochester Castle, leading to his estates, including Eynsford, being forfeited to the Crown.[14] He recovered them after the end of the war and later became the constable of Hertford Castle.[11] His daughter's son, William VI, inherited the castle in 1231; around this time, the hall of the castle burnt down and was rebuilt, complete with glazed windows.[15] Both William VI and his son William VII died young, ending the family line in 1261.[16]

_(17791637304)_(2).jpg)

An enquiry was held to resolve the question of whom should inherit the de Eynsford lands; Eynsford Castle and the other family estates were divided equally between William Heringaud, a powerful landowner in east Kent, and Nicholas de Criol, a smaller local Kentish landowner, both of whom were descended from William V.[16] The Second Barons' War broke out in 1264 and both men supported the rebels against Henry III.[17] Eynsford, by now unoccupied, was seized by Ralph de Farningham, a royal official, who in turn passed it onto Ralph de Sandwich, a royal judge.[17] De Sandwich squeezed the Heringauds out of their inheritance, making a deal in 1292 with Heringaud's daughter, the lady of Horton Kirby, and de Sandwich and the Criols then became joint owners of the castle.[18] Around 1300, the castle was occupied once again, probably either by the widow of Nicholas or William VI, or a castle bailiff.[19]

Ralph de Sandwich sold his share of the castle in 1307 to William Inge, another royal judge.[20] Inge set about exerting his rights over the property, bringing him into conflict with Nicholas's grandson and heir, also called Nicholas de Criol.[21] Conflict broke out and, according to a law case brought by Inge in 1312, Nicholas and two of his brothers attacked several of Inge's properties in the area.[22] Inge claimed, probably accurately, that the de Criols had broken down the doors and windows at Eynsham, ransacked it and released his livestock.[22] The law case was settled two years later, with both men's claims on half of the castle being upheld.[22] It was not reoccupied, although the hall was used when required to hold the local manorial court.[19]

15th–21st centuries

_(18262046960)_(2).jpg)

William Inge's share of Eynsford Castle was inherited by the Zouche family and, when the last of the de Criols died in 1461, the Crown granted the Zouches complete ownership.[19] The castle passed to Lady Elizabeth Chaworth, and on her death in 1501 the Crown gave it to the Harts of Lullingstone Castle.[19] The Harts-Dykes branch of the family later acquired the lordship of the castle and during the 18th century they used the ruined site for their hunting kennels and stables.[23]

In 1835, the castle ceased to be used as kennels and the architect Edward Cresy was employed to remove the more recent modifications.[24] As part of this work he surveyed and excavated parts of the castle, removing up to 9 feet (2.7 m) of accumulated debris.[25] The castle then fell into neglect again, and sections of the north-western walls collapsed in 1872.[26]

A local landowner, E. D. Till, leased the castle in 1897 and undertook restoration work.[26] Agnes Lady Fountain took over the lease after his death in 1917.[27] She agreed to a plan to protect the castle, under which she purchased the freehold and transferred this to the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings in 1937; then, once the leasehold on the property had expired, the castle was passed into the guardianship of the Ministry of Works in 1948.[27]

The site was excavated by S. Rigold between 1953 and 1961 while the castle was being restored, and again between 1966 and 1967 during work to install a new bridge over the moat.[28] Subsequent excavations in the early 1980s by Valerie Horsman led to a substantial reassessment of the fortification's earlier history.[29] In the 21st century, Enysford Castle is controlled by English Heritage and open to visitors; the ruins are protected under UK law as an ancient monument.[30]

Architecture

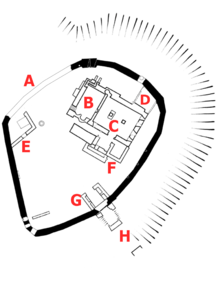

Eynsford Castle originally comprised an inner and an outer bailey, overlooking the River Darent.[31] The outer bailey lay to the south-east of the surviving remains of the castle, but little is known about its shape or the buildings within it.[32] The inner bailey survives as a low earth terrace, or mound, forming an irregular polygon up to 61 metres (200 ft) across, protected by a curtain wall and a moat.[31] Its curtain wall is 9 metres (30 ft) high and almost 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) wide, made of coursed flint rubble reinforced with mural timbers, with ironstone slabs in the putlog and drawbar holes used in its construction.[33] It was built in two phases, the first two thirds in the 11th century, and the upper 3.7 metres (12 ft) in 1130, in part reusing Roman tiles, and it was equipped with three sets of garderobes.[34] The north side of the wall collapsed in the 19th century, and the terrace edge is stabilised by a modern concrete wall.[35]

The inner bailey is reached using a bridge over the moat. The original castle bridge was constructed from wood but this was rebuilt with stone facades and piers in the late medieval period, and then subsequently replaced with an earth bank, further improved in the early 19th century; the current timber bridge dates from the 1960s.[36] A gate house originally protected the entrance, with an arched passageway made from Roman brick, flanked by guardrooms; only the foundations now survive.[37]

In the north-west corner of the bailey are the foundations of the great kitchen.[35] The north-east corner is occupied by the remains of the 12th-century hall complex, built from flint stone, with green sandstone dressings and Roman tiles, and comprising a solar, a hall and forebuildings, of which only the foundations now survive.[38] The solar itself was located on the first floor of the building, with its undercroft forming a separate apartment, probably for the use of the castle bailiff.[35] The first floor of the hall would have been used for public business and living space, and the undercroft used for storage or living space.[39] The forebuilding was 8.5 by 18.3 metres (28 by 60 ft) internally, linked to the hall by a passageway, and provided additional space, and a kitchen was located at the rear of the hall.[40]

Report of ghost sighting

In 2018, several articles of a “Ghostly 'black monk' " at Eynsford Castle, Kent were reported in the tabloids. Jon Wickes and his son visited the castle and took several photographs. Mr. Wickes noticed on returning home from the trip a black ‘shrouded’ figure in the background. He claims in an article that he was sure the figure was not there when he took the picture. Mr. Wickes did a search on the web and found an article about a ghost of a monk being seen in the area. He then went to the paranormal investigator, Alan Tigwell. Tigwell after spending time on the castle’s grounds was quoted in the tabloids as believing there is no other explanation for the image than a ghost of monk. Kenny Biddle, in an article for Skeptical Inquirer, points out that instead of using Occam’s Razor and looking for the most obvious solution, a tourist, Wickes and Tigwell immediately started with the conclusion of a ghostly monk.[41]

References

- Rigold 1972, p. 3

- Rigold 1971, p. 111; Rigold 1972, p. 3

- Horsman 1988, p. 51

- Horsman 1988, p. 53

- Higham & Barker 2004, p. 31; Liddiard 2005, pp. 15–16

- Liddiard 2005, pp. 15–16

- Rigold 1971, p. 111

- Creighton 2002, pp. 70–71

- Rigold 1972, p. 3; Rigold 1971, p. 112

- "History of Eynsford Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 2 October 2016

- Rigold 1972, p. 4

- "History of Eynsford Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 2 October 2016; Horsman 1988, pp. 50, 54

- Rigold 1971, p. 113

- Rigold 1972, p. 4; Rigold 1971, p. 114

- Rigold 1972, pp. 4–5; Rigold 1971, p. 114; "History of Eynsford Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 2 October 2016

- Rigold 1972, p. 5; Rigold 1971, p. 115

- Rigold 1972, p. 5

- Rigold 1972, p. 5; Rigold 1971, p. 116

- Rigold 1972, p. 6

- Rigold 1972, pp. 5–6

- Rigold 1972, p. 6; Rigold 1971, p. 115

- Rigold 1972, p. 6; Rigold 1971, p. 116

- Rigold 1971, p. 116; Rigold 1972, p. 6; Cresy 1838, p. 391

- Cresy 1838, p. 391; "History of Eynsford Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 2 October 2016

- Rigold 1971, p. 109; Cresy 1838, p. 391

- Rigold 1971, p. 116

- Rigold 1971, pp. 109, 116; Rigold 1972, p. 7

- Rigold 1971, p. 109; Wilson & Hurst 1965, p. 190

- Higham & Barker 2004, p. 56; Horsman 1988, p. 43

- "Eynsford Castle", Historic England, retrieved 2 October 2016

- Rigold 1972, p. 8; "Description of Eynsford Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 2 October 2016

- Rigold 1972, p. 8

- Rigold 1972, p. 8; Wilson & Hurst 1965, p. 190; "Description of Eynsford Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 2 October 2016

- Rigold 1972, pp. 8–9; "Description of Eynsford Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 2 October 2016

- "Description of Eynsford Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 2 October 2016

- Rigold 1972, p. 10; Wilson & Hurst 1965, p. 190; Rigold & Fleming 1973, p. 88

- Rigold 1972, p. 11

- Rigold 1972, pp. 11–12

- Rigold 1972, p. 12

- Rigold 1972, pp. 13–14; "Description of Eynsford Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 2 October 2016

- Biddle, Kenny (24 April 2018). "Ghostly 'Black Monk' or Random Tourist?". The Center for Inquiry. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

Bibliography

- Creighton, Oliver Hamilton (2002). Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England. London, UK: Equinox. ISBN 978-1-904768-67-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cresy, E. (1838). "Eynsford Castle, in the County of Kent". Archaeologia. 27: 391–397.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Higham, Robert; Barker, Philip (2004) [1992]. Timber Castles. Exeter, UK: University of Exeter Press. ISBN 978-0-85989-753-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Horsman, Valerie (1988). "Eynsford Castle: A Reinterpretation of its Early History in the Light of Recent Excavations". Archaeologia Cantiana. 105: 39–58.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Liddiard, Robert (2005). Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism and Landscape, 1066 to 1500. Macclesfield, UK: Windgather Press. ISBN 0-9545575-2-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rigold, S. E. (1971). "Eynsford Castle and its Excavation". Archaeologia Cantiana. 86: 109–171.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rigold, S. E. (1972) [1964]. Eynsford Castle, Kent (amended ed.). London, UK: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. OCLC 222244601.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rigold, S. E.; Fleming, A. J. (1973). "Eynsford Castle: The Moat and Bridge". Archaeologia Cantiana. 88: 87–116.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilson, D. M.; Hurst, J. G. (1965). "Medieval Britain in 1964". Medieval Archaeology. 9: 170–220.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eynsford Castle. |