Examples of groups

Some elementary examples of groups in mathematics are given on Group (mathematics). Further examples are listed here.

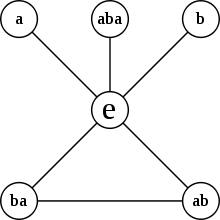

Permutations of a set of three elements

Consider three colored blocks (red, green, and blue), initially placed in the order RGB. Let a be the operation "swap the first block and the second block", and b be the operation "swap the second block and the third block".

We can write xy for the operation "first do y, then do x"; so that ab is the operation RGB → RBG → BRG, which could be described as "move the first two blocks one position to the right and put the third block into the first position". If we write e for "leave the blocks as they are" (the identity operation), then we can write the six permutations of the three blocks as follows:

- e : RGB → RGB

- a : RGB → GRB

- b : RGB → RBG

- ab : RGB → BRG

- ba : RGB → GBR

- aba : RGB → BGR

Note that aa has the effect RGB → GRB → RGB; so we can write aa = e. Similarly, bb = (aba)(aba) = e; (ab)(ba) = (ba)(ab) = e; so every element has an inverse.

By inspection, we can determine associativity and closure; note in particular that (ba)b = bab = b(ab).

Since it is built up from the basic operations a and b, we say that the set {a,b} generates this group. The group, called the symmetric group S3, has order 6, and is non-abelian (since, for example, ab ≠ ba).

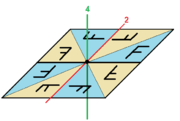

The group of translations of the plane

A translation of the plane is a rigid movement of every point of the plane for a certain distance in a certain direction. For instance "move in the North-East direction for 2 miles" is a translation of the plane. If you have two such translations a and b, they can be composed to form a new translation a ∘ b as follows: first follow the prescription of b, then that of a. For instance, if

- a = "move North-East for 3 miles"

and

- b = "move South-East for 4 miles"

then

- a ∘ b = "move East for 5 miles"

(see Pythagorean theorem for why this is so, geometrically).

The set of all translations of the plane with composition as operation forms a group:

- If a and b are translations, then a ∘ b is also a translation.

- Composition of translations is associative: (a ∘ b) ∘ c = a ∘ (b ∘ c).

- The identity element for this group is the translation with prescription "move zero miles in whatever direction you like".

- The inverse of a translation is given by walking in the opposite direction for the same distance.

This is an abelian group and our first (nondiscrete) example of a Lie group: a group which is also a manifold.

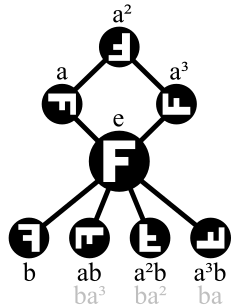

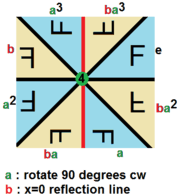

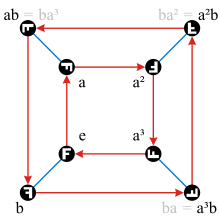

The symmetry group of a square: dihedral group of order 8

a is the clockwise rotation

and b the horizontal reflection.

Dih4 as 2D point group, D4, [4], (*4•), order 4, with a 4-fold rotation and a mirror generator. |

Dih4 in 3D dihedral group D4, [4,2]+, (422), order 4, with a vertical 4-fold rotation generator order 4, and 2-fold horizontal generator |

Groups are very important to describe the symmetry of objects, be they geometrical (like a tetrahedron) or algebraic (like a set of equations). As an example, we consider a glass square of a certain thickness (with a letter "F" written on it, just to make the different positions discriminable). In order to describe its symmetry, we form the set of all those rigid movements of the square that don't make a visible difference (except the "F"). For instance, if you turn it by 90° clockwise, then it still looks the same, so this movement is one element of our set, let's call it a. We could also flip it horizontally so that its underside becomes its top side, while the left edge becomes the right edge. Again, after performing this movement, the glass square looks the same, so this is also an element of our set and we call it b. Then there's of course the movement that does nothing; it's denoted by e.

Now if you have two such movements x and y, you can define the composition x ∘ y as above: you first perform the movement y and then the movement x. The result will leave the slab looking like before.

The point is that the set of all those movements, with composition as operation, forms a group. This group is the most concise description of the square's symmetry. Chemists use symmetry groups of this type to describe the symmetry of crystals and molecules.

Generating the group

Let's investigate our squares symmetry group some more. Right now, we have the elements a, b and e, but we can easily form more: for instance a ∘ a, also written as a2, is a 180° degree turn. a3 is a 270° clockwise rotation (or a 90° counter-clockwise rotation). We also see that b2 = e and also a4 = e. Here's an interesting one: what does a ∘ b do? First flip horizontally, then rotate. Try to visualize that a ∘ b = b ∘ a3. Also, a2 ∘ b is a vertical flip and is equal to b ∘ a2.

We say that elements a, b and e generate the group.

This group of order 8 has the following Cayley table:

| o | e | b | a | a2 | a3 | ab | a2b | a3b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| e | e | b | a | a2 | a3 | ab | a2b | a3b |

| b | b | e | a3b | a2b | ab | a3 | a2 | a |

| a | a | ab | a2 | a3 | e | a2b | a3b | b |

| a2 | a2 | a2b | a3 | e | a | a3b | b | ab |

| a3 | a3 | a3b | e | a | a2 | b | ab | a2b |

| ab | ab | a | b | a3b | a2b | e | a3 | a2 |

| a2b | a2b | a2 | ab | b | a3b | a | e | a3 |

| a3b | a3b | a3 | a2b | ab | b | a2 | a | e |

For any two elements in the group, the table records what their composition is.

Here we wrote "a3b" as a shorthand for a3 ∘ b.

In mathematics this group is known as the dihedral group of order 8, and is either denoted Dih4, D4 or D8, depending on the convention. This was an example of a non-abelian group: the operation ∘ here is not commutative, which you can see from the table; the table is not symmetrical about the main diagonal.

The dihedral group of order 8 is isomorphic to the permutation group generated by (1234) and (13).

Normal subgroup

This version of the Cayley table shows that this group has one normal subgroup shown with a red background. In this table r means rotations, and f means flips. Because the subgroup in normal, the left coset is the same as the right coset.

| e | r1 | r2 | r3 | fv | fh | fd | fc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| e | e | r1 | r2 | r3 | fv | fh | fd | fc |

| r1 | r1 | r2 | r3 | e | fc | fd | fv | fh |

| r2 | r2 | r3 | id | r1 | fh | fv | fc | fd |

| r3 | r3 | e | r1 | r2 | fd | fc | fh | fv |

| fv | fv | fd | fh | fc | e | r2 | r1 | r3 |

| fh | fh | fc | fv | fd | r2 | e | r3 | r1 |

| fd | fd | fh | fc | fv | r3 | r1 | e | r2 |

| fc | fc | fv | fd | fh | r1 | r3 | r2 | e |

| The elements id, r1, r2, and r3 form a subgroup, highlighted in red (upper left region). A left and right coset of this subgroup is highlighted in green (in the last row) and yellow (last column), respectively. | ||||||||

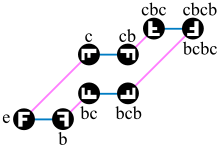

Free group on two generators

The free group with two generators a and b consists of all finite strings that can be formed from the four symbols a, a−1, b and b−1 such that no a appears directly next to an a−1 and no b appears directly next to a b−1. Two such strings can be concatenated and converted into a string of this type by repeatedly replacing the "forbidden" substrings with the empty string. For instance: "abab−1a−1" concatenated with "abab−1a" yields "abab−1a−1abab−1a", which gets reduced to "abaab−1a". One can check that the set of those strings with this operation forms a group with neutral element the empty string ε := "". (Usually the quotation marks are left off, which is why you need the symbol ε!)

This is another infinite non-abelian group.

Free groups are important in algebraic topology; the free group in two generators is also used for a proof of the Banach–Tarski paradox.

The set of maps

The sets of maps from a set to a group

Let G be a group and S a nonempty set. The set of maps M(S, G) is itself a group; namely for two maps f,g of S into G we define fg to be the map such that (fg)(x) = f(x)g(x) for every x∈S and f−1 to be the map such that f−1(x) = f(x)−1.

Take maps f, g, and h in M(S,G). For every x in S, f(x) and g(x) are both in G, and so is (fg)(x). Therefore, fg is also in M(S, G), or M(S, G) is closed. For ((fg)h)(x) = (fg)(x)h(x) = (f(x)g(x))h(x) = f(x)(g(x)h(x)) = f(x)(gh)(x) = (f(gh))(x), M(S, G) is associative. And there is a map i such that i(x) = e where e is the unit element of G. The map i makes all the functions f in M(S, G) such that if = fi = f, or i is the unit element of M(S, G). Thus, M(S, G) is actually a group.

If G is commutative, then (fg)(x) = f(x)g(x) = g(x)f(x) = (gf)(x). Therefore, so is M(S, G).

Automorphism groups

Groups of permutations

Let G be the set of bijective mappings of a set S onto itself. Then G forms a group under ordinary composition of mappings. This group is called the symmetric group, and is commonly denoted Sym(S), ΣS, or . The unit element of G is the identity map of S. For two maps f and g in G are bijective, fg is also bijective. Therefore, G is closed. The composition of maps is associative; hence G is a group. S may be either finite or infinite.

Matrix groups

If n is some positive integer, we can consider the set of all invertible n by n matrices over the reals, say. This is a group with matrix multiplication as operation. It is called the general linear group, GL(n). Geometrically, it contains all combinations of rotations, reflections, dilations and skew transformations of n-dimensional Euclidean space that fix a given point (the origin).

If we restrict ourselves to matrices with determinant 1, then we get another group, the special linear group, SL(n). Geometrically, this consists of all the elements of GL(n) that preserve both orientation and volume of the various geometric solids in Euclidean space.

If instead we restrict ourselves to orthogonal matrices, then we get the orthogonal group O(n). Geometrically, this consists of all combinations of rotations and reflections that fix the origin. These are precisely the transformations which preserve lengths and angles.

Finally, if we impose both restrictions, then we get the special orthogonal group SO(n), which consists of rotations only.

These groups are our first examples of infinite non-abelian groups. They are also happen to be Lie groups. In fact, most of the important Lie groups (but not all) can be expressed as matrix groups.

If this idea is generalised to matrices with complex numbers as entries, then we get further useful Lie groups, such as the unitary group U(n). We can also consider matrices with quaternions as entries; in this case, there is no well-defined notion of a determinant (and thus no good way to define a quaternionic "volume"), but we can still define a group analogous to the orthogonal group, the symplectic group Sp(n).

Furthermore, the idea can be treated purely algebraically with matrices over any field, but then the groups are not Lie groups.

For example, we have the general linear groups over finite fields. The group theorist J. L. Alperin has written that "The typical example of a finite group is GL(n,q), the general linear group of n dimensions over the field with q elements. The student who is introduced to the subject with other examples is being completely misled." (Bulletin (New Series) of the American Mathematical Society, 10 (1984) 121)

Some more finite groups

- List of small groups

- List of the 230 crystallographic 3D space groups