Evaluation of binary classifiers

The evaluation of binary classifiers compares two methods of assigning a binary attribute, one of which is usually a standard method and the other is being investigated. There are many metrics that can be used to measure the performance of a classifier or predictor; different fields have different preferences for specific metrics due to different goals. For example, in medicine sensitivity and specificity are often used, while in computer science precision and recall are preferred. An important distinction is between metrics that are independent on the prevalence (how often each category occurs in the population), and metrics that depend on the prevalence – both types are useful, but they have very different properties.

Sources: Balayla (2020),[1] Fawcett (2006),[2] Powers (2011),[3] Ting (2011),[4] and CAWCR[5] Chicco & Jurman (2020),[6] Tharwat (2018).[7] |

Contingency table

Given a data set, a classification (the output of a classifier on that set) gives two numbers: the number of positives and the number of negatives, which add up to the total size of the set. To evaluate a classifier, one compares its output to another reference classification – ideally a perfect classification, but in practice the output of another gold standard test – and cross tabulates the data into a 2×2 contingency table, comparing the two classifications. One then evaluates the classifier relative to the gold standard by computing summary statistics of these 4 numbers. Generally these statistics will be scale invariant (scaling all the numbers by the same factor does not change the output), to make them independent of population size, which is achieved by using ratios of homogeneous functions, most simply homogeneous linear or homogeneous quadratic functions.

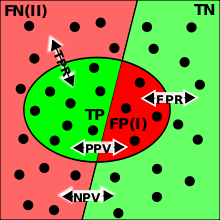

Say we test some people for the presence of a disease. Some of these people have the disease, and our test correctly says they are positive. They are called true positives (TP). Some have the disease, but the test incorrectly claims they don't. They are called false negatives (FN). Some don't have the disease, and the test says they don't – true negatives (TN). Finally, there might be healthy people who have a positive test result – false positives (FP). These can be arranged into a 2×2 contingency table (confusion matrix), conventionally with the test result on the vertical axis and the actual condition on the horizontal axis.

These numbers can then be totaled, yielding both a grand total and marginal totals. Totaling the entire table, the number of true positives, false negatives, true negatives, and false positives add up to 100% of the set. Totaling the rows (adding horizontally) the number of true positives and false positives add up to 100% of the test positives, and likewise for negatives. Totaling the columns (adding vertically), the number of true positives and false negatives add up to 100% of the condition positives (conversely for negatives). The basic marginal ratio statistics are obtained by dividing the 2×2=4 values in the table by the marginal totals (either rows or columns), yielding 2 auxiliary 2×2 tables, for a total of 8 ratios. These ratios come in 4 complementary pairs, each pair summing to 1, and so each of these derived 2×2 tables can be summarized as a pair of 2 numbers, together with their complements. Further statistics can be obtained by taking ratios of these ratios, ratios of ratios, or more complicated functions.

The contingency table and the most common derived ratios are summarized below; see sequel for details.

| True condition | ||||||

| Total population | Condition positive | Condition negative | Prevalence = Σ Condition positive/Σ Total population | Accuracy (ACC) = Σ True positive + Σ True negative/Σ Total population | ||

| Predicted condition |

Predicted condition positive |

True positive | False positive, Type I error |

Positive predictive value (PPV), Precision = Σ True positive/Σ Predicted condition positive | False discovery rate (FDR) = Σ False positive/Σ Predicted condition positive | |

| Predicted condition negative |

False negative, Type II error |

True negative | False omission rate (FOR) = Σ False negative/Σ Predicted condition negative | Negative predictive value (NPV) = Σ True negative/Σ Predicted condition negative | ||

| True positive rate (TPR), Recall, Sensitivity, probability of detection, Power = Σ True positive/Σ Condition positive | False positive rate (FPR), Fall-out, probability of false alarm = Σ False positive/Σ Condition negative | Positive likelihood ratio (LR+) = TPR/FPR | Diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) = LR+/LR− | F1 score = 2 · Precision · Recall/Precision + Recall | ||

| False negative rate (FNR), Miss rate = Σ False negative/Σ Condition positive | Specificity (SPC), Selectivity, True negative rate (TNR) = Σ True negative/Σ Condition negative | Negative likelihood ratio (LR−) = FNR/TNR | ||||

Note that the columns correspond to the condition actually being positive or negative (or classified as such by the gold standard), as indicated by the color-coding, and the associated statistics are prevalence-independent, while the rows correspond to the test being positive or negative, and the associated statistics are prevalence-dependent. There are analogous likelihood ratios for prediction values, but these are less commonly used, and not depicted above.

Sensitivity and specificity

The fundamental prevalence-independent statistics are sensitivity and specificity.

Sensitivity or True Positive Rate (TPR), also known as recall, is the proportion of people that tested positive and are positive (True Positive, TP) of all the people that actually are positive (Condition Positive, CP = TP + FN). It can be seen as the probability that the test is positive given that the patient is sick. With higher sensitivity, fewer actual cases of disease go undetected (or, in the case of the factory quality control, fewer faulty products go to the market).

Specificity (SPC) or True Negative Rate (TNR) is the proportion of people that tested negative and are negative (True Negative, TN) of all the people that actually are negative (Condition Negative, CN = TN + FP). As with sensitivity, it can be looked at as the probability that the test result is negative given that the patient is not sick. With higher specificity, fewer healthy people are labeled as sick (or, in the factory case, fewer good products are discarded).

The relationship between sensitivity and specificity, as well as the performance of the classifier, can be visualized and studied using the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve.

In theory, sensitivity and specificity are independent in the sense that it is possible to achieve 100% in both (such as in the red/blue ball example given above). In more practical, less contrived instances, however, there is usually a trade-off, such that they are inversely proportional to one another to some extent. This is because we rarely measure the actual thing we would like to classify; rather, we generally measure an indicator of the thing we would like to classify, referred to as a surrogate marker. The reason why 100% is achievable in the ball example is because redness and blueness is determined by directly detecting redness and blueness. However, indicators are sometimes compromised, such as when non-indicators mimic indicators or when indicators are time-dependent, only becoming evident after a certain lag time. The following example of a pregnancy test will make use of such an indicator.

Modern pregnancy tests do not use the pregnancy itself to determine pregnancy status; rather, human chorionic gonadotropin is used, or hCG, present in the urine of gravid females, as a surrogate marker to indicate that a woman is pregnant. Because hCG can also be produced by a tumor, the specificity of modern pregnancy tests cannot be 100% (because false positives are possible). Also, because hCG is present in the urine in such small concentrations after fertilization and early embryogenesis, the sensitivity of modern pregnancy tests cannot be 100% (because false negatives are possible).

Likelihood ratios

Positive and negative predictive values

In addition to sensitivity and specificity, the performance of a binary classification test can be measured with positive predictive value (PPV), also known as precision, and negative predictive value (NPV). The positive prediction value answers the question "If the test result is positive, how well does that predict an actual presence of disease?". It is calculated as TP/(TP + FP); that is, it is the proportion of true positives out of all positive results. The negative prediction value is the same, but for negatives, naturally.

Impact of prevalence on prediction values

Prevalence has a significant impact on prediction values. As an example, suppose there is a test for a disease with 99% sensitivity and 99% specificity. If 2000 people are tested and the prevalence (in the sample) is 50%, 1000 of them are sick and 1000 of them are healthy. Thus about 990 true positives and 990 true negatives are likely, with 10 false positives and 10 false negatives. The positive and negative prediction values would be 99%, so there can be high confidence in the result.

However, if the prevalence is only 5%, so of the 2000 people only 100 are really sick, then the prediction values change significantly. The likely result is 99 true positives, 1 false negative, 1881 true negatives and 19 false positives. Of the 19+99 people tested positive, only 99 really have the disease – that means, intuitively, that given that a patient's test result is positive, there is only 84% chance that they really have the disease. On the other hand, given that the patient's test result is negative, there is only 1 chance in 1882, or 0.05% probability, that the patient has the disease despite the test result.

Likelihood ratios

Precision and recall

Relationships

There are various relationships between these ratios.

If the prevalence, sensitivity, and specificity are known, the positive predictive value can be obtained from the following identity:

If the prevalence, sensitivity, and specificity are known, the negative predictive value can be obtained from the following identity:

Single metrics

In addition to the paired metrics, there are also single metrics that give a single number to evaluate the test.

Perhaps the simplest statistic is accuracy or fraction correct (FC), which measures the fraction of all instances that are correctly categorized; it is the ratio of the number of correct classifications to the total number of correct or incorrect classifications: (TP + TN)/total population = (TP + TN)/(TP + TN + FP + FN). This is often not very useful, compared to the marginal ratios, as it does not yield useful marginal interpretations, due to mixing true positives (test positive, condition positive) and true negatives (test negative, condition negative) – in terms of the condition table, it sums the diagonal; further, it is prevalence-dependent. The complement is the fraction incorrect (FiC): FC + FiC = 1, or (FP + FN)/(TP + TN + FP + FN) – this is the sum of the antidiagonal, divided by the total population.

The diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) is a more useful overall metric, which can be defined directly as (TP×TN)/(FP×FN) = (TP/FN)/(FP/TN), or indirectly as a ratio of ratio of ratios (ratio of likelihood ratios, which are themselves ratios of true rates or prediction values). This has a useful interpretation – as an odds ratio – and is prevalence-independent.

An F-score is a combination of the precision and the recall, providing a single score. There is a one-parameter family of statistics, with parameter β, which determines the relative weights of precision and recall. The traditional or balanced F-score (F1 score) is the harmonic mean of precision and recall:

- .

Alternative metrics

Note, however, that the F-scores do not take the true negative rate into account, and are more suited to information retrieval and information extraction evaluation where the true negatives are innumerable. Instead, measures such as the phi coefficient, Matthews correlation coefficient, informedness or Cohen's kappa may be preferable to assess the performance of a binary classifier.[8][9] As a correlation coefficient, the Matthews correlation coefficient is the geometric mean of the regression coefficients of the problem and its dual. The component regression coefficients of the Matthews correlation coefficient are markedness (deltap) and informedness (Youden's J statistic or deltap').[10]

See also

- Population impact measures

- Attributable risk

- Attributable risk percent

- Scoring rule (for probability predictions)

References

- Balayla, Jacques (2020). "Prevalence Threshold and the Geometry of Screening Curves". arXiv:2006.00398.

- Fawcett, Tom (2006). "An Introduction to ROC Analysis" (PDF). Pattern Recognition Letters. 27 (8): 861–874. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2005.10.010.

- Powers, David M W (2011). "Evaluation: From Precision, Recall and F-Measure to ROC, Informedness, Markedness & Correlation". Journal of Machine Learning Technologies. 2 (1): 37–63.

- Ting, Kai Ming (2011). Sammut, Claude; Webb, Geoffrey I (eds.). Encyclopedia of machine learning. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-30164-8. ISBN 978-0-387-30164-8.

- Brooks, Harold; Brown, Barb; Ebert, Beth; Ferro, Chris; Jolliffe, Ian; Koh, Tieh-Yong; Roebber, Paul; Stephenson, David (2015-01-26). "WWRP/WGNE Joint Working Group on Forecast Verification Research". Collaboration for Australian Weather and Climate Research. World Meteorological Organisation. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- Chicco D, Jurman G (January 2020). "The advantages of the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) over F1 score and accuracy in binary classification evaluation". BMC Genomics. 21 (1): 6-1–6-13. doi:10.1186/s12864-019-6413-7. PMC 6941312. PMID 31898477.

- Tharwat A (August 2018). "Classification assessment methods". Applied Computing and Informatics. doi:10.1016/j.aci.2018.08.003.

- Powers, David M W (2011). "Evaluation: From Precision, Recall and F-Score to ROC, Informedness, Markedness & Correlation". Journal of Machine Learning Technologies. 2 (1): 37–63. hdl:2328/27165.

- Powers, David M. W. (2012). "The Problem with Kappa" (PDF). Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (EACL2012) Joint ROBUS-UNSUP Workshop. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-05-18. Retrieved 2012-07-20.

- Perruchet, P.; Peereman, R. (2004). "The exploitation of distributional information in syllable processing". J. Neurolinguistics. 17 (2–3): 97–119. doi:10.1016/S0911-6044(03)00059-9. S2CID 17104364.