Eugene Landy

Eugene Ellsworth Landy (November 26, 1934 – March 22, 2006) was an American psychotherapist known for his unconventional 24-hour therapy and especially for his treatment of the Beach Boys co-founder Brian Wilson in the 1970s and 1980s. His treatment of Wilson was deemed unethical by Californian courts and was later dramatized in the 2014 biographical film Love & Mercy, in which Landy is portrayed by Paul Giamatti.

Eugene Landy | |

|---|---|

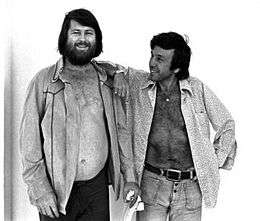

Landy (right) with patient Brian Wilson, 1976 | |

| Born | Eugene Ellsworth Landy November 26, 1934 Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, US |

| Died | March 22, 2006 (aged 71) Honolulu, Hawaii, US |

| Other names | Gene Landy[1] |

| Education |

|

| Occupation | Psychologist, psychotherapist, writer, record producer, businessman |

| Organization |

|

| Known for | 24-hour therapy and alleged exploitation of Brian Wilson |

Notable work |

|

| Partner(s) | Alexandra Morgan (1975–2006) |

| Children | 1 |

As a teenager, Landy aspired to show business, briefly serving as an early manager for George Benson. During the 1960s, he began studying psychology, earning his doctorate at the University of Oklahoma. After moving to Los Angeles, he treated many celebrity clients, including musician Alice Cooper and actors Richard Harris, Rod Steiger, Maureen McCormick, and Gig Young. He also developed an unorthodox 24-hour regimen intended to stabilize his patients by micromanaging their lives with a team of counselors and doctors.

Brian Wilson initially became a patient under Landy's program in 1975. Landy was soon discharged due to his burdensome fees. In 1982, Landy was re-employed as Wilson's therapist, subsequently becoming his executive producer, business manager, co-songwriter, and business adviser. Landy went on to co-produce Wilson's debut solo album Brian Wilson (1988) and its unreleased follow-up Sweet Insanity (1991), as well as allegedly ghostwriting portions of Wilson's disowned memoir Wouldn't It Be Nice: My Own Story (1991).

In 1989, Landy agreed to let the state of California revoke his professional license amidst accusations of ethical violations and patient misconduct. Wilson continued to see Landy until a 1992 restraining order barred Landy from contacting the musician ever again. After the 1990s, Landy continued a psychotherapy practice with licensure in New Mexico and Hawaii until his death.

Early life and education

Eugene Ellsworth Landy was born on November 26, 1934, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the only child of Jules C. Landy, a medical doctor and psychology professor,[2] and Frieda Mae Gordon Landy, also a psychology professor.[3] Eugene dropped out of school in the sixth grade, later claiming to be dyslexic.[2][3] At age 16, he pursued a career in show business, producing a nationally syndicated radio show, and discovering 10-year-old George Benson.[2][4] Landy briefly served as Benson's manager[4] and worked odd jobs as a radio producer, promoting records and producing a single for Frankie Avalon.[3]

Honoring his parents' wishes, Landy resumed his psychiatric studies at Los Angeles City College, where he earned an AA in chemistry, and entered medical school at the National University of Mexico. After falling ill with dysentery, he switched to psychology.[3] He earned a master's degree in psychology from the University of Oklahoma in 1967, completing his training with a PhD in 1968.[2]

Career and development of methods

—Eugene Landy, Handbook of Innovative Psychotherapies, 1981[3]

After completing his studies, Landy worked for the Peace Corps, eventually moving to Los Angeles[5] to work as a drug counselor at Harbor Hospital and as a popular part-time instructor at San Fernando Valley State College. Landy began developing ideas for his 24-hour treatment program while engaging in postdoctoral work at Rancho Santa Fe.[3] It was there that he practiced "marathon therapy", in which a therapist takes control of a group of people for a day or more.[3] In 1968, he worked briefly as an intern at Gateways Hospital in Echo Park, Los Angeles, where he developed his methods further, experimenting with treatment on teenage drug abusers with varying degrees of success. He attributed his failures to having too little control over their nighttime activities; he tried evening rap groups and made himself available at all hours for talking therapies for their nocturnal anxiety attacks.[3] Landy went on to call his new system milieu therapy.[6]

While serving the hospital, Landy became cultured in the lingo used by its teenagers.[3] In 1971, he authored a book on hippie jargon called The Underground Dictionary,[2][5] published by Simon & Schuster.[7]

Around 1972, Landy founded a Beverly Hills clinic, the Foundation for the Rechanneling of Emotions and Education (FREE).[8] Interns employed at the clinic used Landy's approach on a partial basis.[9] In the early 1970s, he also started penetrating Hollywood social circles, becoming a consultant on various television shows including The Bob Newhart Show.[3][7] He soon began treating many celebrity clients, earning $200 an hour.[7]

Some of Landy's patients included Alice Cooper, Richard Harris, Rod Steiger, and Gig Young, who died in an apparent murder-suicide along with his wife in 1978.[4] In a 1976 interview with Rolling Stone, Landy claimed that he had treated others, but that he was in no position to explain his background. He added, "I've treated a tremendous number of people in show business; for some reason I seem to be able to relate to them. I think I have a nice reputation that says I'm unorthodox by orthodox standards but basically unique by unorthodox standards."[5] Unusually, he had his own press kit.[3]

In 1988, psychiatrist and Landy colleague Sol Samuels described Landy as "a maverick in the field of psychology. He's done things that no other psychologist has done in treating the psychotic and the drug addict. ... What he was doing really was translating the hospital environment to the home environment. I think he got some remarkable results – with people who can afford it."[3]

Treatment of Brian Wilson

First treatment (1975–1976)

Landy was initially hired to treat Brian Wilson by Wilson's wife Marilyn in 1975.[10] Wilson publicly rebelled against the program, saying that the only reason that he went along with it was so that he would not be committed to a psychiatric facility.[3] Beach Boys road manager Rick Nelson later claimed that Landy had attempted to exert unwelcome artistic control over the group.[3] During the recording of the Beach Boys' album 15 Big Ones (1976), group meetings were supervised by Landy, and discussions over each song for the record were reported to last for up to eight hours.[11] Another report suggested that Landy had asked for a percentage of the band's income.[12] At Landy's insistence, Wilson appeared on Saturday Night Live, choosing to perform a solo piano rendition of "Good Vibrations" which received mixed feedback.[13] Landy stood off-camera holding signs for Wilson that read "smile". He said that critics missed the point of this exercise, explaining that Wilson's performance "was a terrible thing" as a one-shot, but if he continued making appearances then he would have gradually overcome his stage fright.[13]

Steve Love, Wilson's cousin and band manager, fired Landy in December 1976 when Landy doubled his fee.[3][14][4] Landy remembered 15 Big Ones as "the only major success" the Beach Boys had in recent years; "Brian and I did that together. Right after that, I had to leave the situation. ... I was interested in making Brian a whole human being; they [the Beach Boys management] were interested in getting another album done in time for 1977."[15] In 1977, Wilson was asked if Landy had too much control; he said, "I thought so, but there was nothing I could do about it and I eventually gave in to it. ... [He had] control of my life legally through the commitment of my wife. ... He definitely helped me. It cost over a hundred thousand dollars – he charged a hell of a lot per month."[13] Wilson then reported that Landy was replaced with a different doctor.[13]

Second treatment (1982–1992)

In 1982, Wilson was brought back to Landy's care after overdosing on a combination of alcohol, cocaine, and other psychoactive drugs.[4] Landy monitored Wilson's drug intake and used the psychiatrist Sol Samuels to prescribe Wilson medication. Landy's assistant Kevin Leslie stood with Wilson at every moment, earning Leslie the nickname "Surf Nazi". Leslie also gave Wilson medication at Landy's direction. Initially, Leslie was paid salary by Landy, but was eventually paid directly by Wilson.[7] In 1988, Samuels took credit with performing the "actual supervision of the therapy ... giving the medication and the occasional psychotherapy as he needs it. What Gene has been doing is hiring the people to be with him, and so forth, much as a parent would do if asked to get some help in the house."[3]

In the mid 1980s, Landy stated of Wilson, "I influence all of his thinking. I'm practically a member of the band ... [We're] partners in life."[16] Wilson later responded to popular allegations, "People say that Dr. Landy runs my life, but the truth is, I'm in charge."[17] Landy echoed: "He's got a car phone in his car. If he wants to call somebody, he calls somebody. ... He can go anywhere, on his own, anytime he wants."[15] An August 1988 issue of Rolling Stone states the following:

During the course of eight days spent with Landy and Wilson, it became clear just how much control Landy exerts over Brian's life. With the exception of taking a brief drive by himself to the market to pick up groceries, Brian appeared to be incapable of making a move without Landy's okay. During one interview session, the Landy line seemed to ring every thirty minutes. Yet Brian appears to be a willing participant in the program.[7]

Even though the Beach Boys had hired Landy, part of the regimen involved cutting Wilson's contact from the group, as Landy reasoned: "You can't deal with people who only want to use you."[15] Wilson said that "Dr. Landy doesn't like me to be in touch with my family too much. He thinks it's unhealthy."[15] For example, Brian remembered participating in an interview with his brother Carl Wilson, "and the interviewer asked Carl what it was between him and me. He goes, 'Well, Brian and I don't have to talk to each other. We're just Beach Boys, but we don't need to be friends.' And that's true. Although, whenever I think about him, I feel rotten."[15]

In 1986, Wilson met his future wife and manager Melinda Ledbetter, a Cadillac saleswoman and former model, while browsing through a car dealership.[18] Six months after meeting Wilson, she had reported Landy to the state's attorney general, who informed her that nothing could be done without the cooperation of Wilson's family. Ledbetter felt that the family had been at their "rope's end" with Wilson, and that they did not know what to do to help him. She said that three years into their relationship, Landy ordered Wilson to sever ties with her.[19]

Music and business associations

Between 1983 and 1986, Landy charged about $430,000 annually, forcing Wilson's family members to devote some publishing rights to his fee.[4] Landy received 25% of the copyright to all of Wilson's songs, regardless of whether he contributed to them or not, which band manager Tom Hulett explained was an incentive for Landy to reignite Wilson's drive. "It was sort of like, 'Gee, there's nothing coming in now, if you can go make this person well to go create some income ...'"[3] Landy expressed similar views. "Saying that [I would share in future songwriting royalties] in '84 was like me telling you, 'I'll pay you a million dollars if you can get up and fly around the room.'"[20] This arrangement was revoked in 1985, with Landy only receiving rights with a percentage equal to his writing contributions.[3] Landy reported that he never received any money, since Wilson had not published any material before the pact was voided.[20] Afterward, Wilson paid Landy a salary of about $300,000 a year for advice on creative decisions.[20]

In late 1987, Landy and Wilson became creative partners in a company called Brains and Genius, a business venture where each member would contribute equally and share any profits from recordings, films, soundtracks, or books.[20] Landy was then credited as co-writer and executive producer for Wilson's debut solo album, Brian Wilson, released in 1988.[4] Co-producer Russ Titelman disparaged Landy's role in the album's creation, calling him disruptive and "anti-creative".[3] Wilson's cousin and bandmate Mike Love denied Landy's claims that the Beach Boys were preventing Wilson from participating on their recordings, and believed that the reason Landy encouraged Wilson to pursue a solo career "was to destroy us. Then he would be the sole custodian of Brian's career and legacy."[23] Landy maintained that his songwriting collaborations on Brian Wilson earned him less than $50,000.[20]

For the publishing of Wilson's autobiographic memoir, Wouldn't It Be Nice: My Own Story, Landy stood to earn 30% of its proceeds.[24] The book glorifies Landy and its contents were challenged for plagiarism. Landy denied accusations that he was involved as a ghostwriter. Wilson later distanced himself from the book.[25] In a 1995 court case, Wilson's lawyers argued that HarperCollins were aware that Wilson's statements in the book were either manipulated or written by Landy.[26]

State intervention

Action was taken against Landy's professional practice as a result of the Beach Boys' and Wilson family's struggles for control.[4] A former nurse and girlfriend of Wilson's brought Landy to the state's attention in 1984. The state was then aided by journals written by songwriter Gary Usher during a ten-month collaboration with Wilson. These journals depicted Wilson as a virtual captive dominated by Landy, who was determined to fulfill his show business ambitions through Wilson.[3] By this time, Wilson had become Landy's only patient.[20]

In February 1988, the State of California Board of Medical Quality charged Landy with ethical and license code violations stemming from the improper prescription of drugs and various unethical personal and professional relationships with patients, citing one case of sexual misconduct with a female patient, along with Wilson's psychological dependency on Landy.[3] Landy denied the allegations, but later admitted to one of the seven charges which accused him of wrongfully prescribing drugs to Wilson. Landy surrendered his psychological license, complying with an agreement made with the state of California, and was not allowed applications for reinstatement for the next two years.[8]

—Wilson's psychiatrist Sol Samuels, 1988[3]

An August 1988 board meeting with the Beach Boys had Landy promising that Brian would reconnect with the group, which Love says: "was a ruse to get us to write a letter in his defense against the California authorities. We never wrote the letter, and Brian's public behavior continued to unsettle."[27] Landy and his colleagues said that his treatment of Wilson ended in February 1988 at the request of the state attorney general's office, but the deputy attorney who drafted the complaint reported that he was not aware of any such request, nor was the office advised that they sever Landy's relationship with Wilson.[3] Co-producers of Wilson's solo album said they witnessed no changes, and Landy's assistants remained with Wilson. Sol Samuels said this was because Landy had little direct involvement with Wilson's treatment, and that it was instead the people Landy hired who continued to regulate Wilson's medication.[3]

According to songwriter P. F. Sloan, Landy took advantage of Sloan's disappearance and claimed at one point to be the real P. F. Sloan.[28] He explains that it was an attempt by Landy to gain credibility and appease members of the medical community who were questioning why Landy felt that he was an appropriate songwriting collaborator for Wilson.[29]

Conservatorship hearings

Peter Reum, a therapist who met Wilson while attending a Beach Boys fan convention in 1990, was alarmed by Wilson's demeanor and speculated that he may be suffering from tardive dyskinesia, a neurological condition brought on by prolonged usage of antipsychotic medication.[30] Reum phoned biographer David Leaf, who then reported Reum's observations to Carl Wilson.[31] It was then discovered that Landy had been named as a chief beneficiary in a 1989 revision of Brian's will,[31] collecting 70%, with the remainder split between his girlfriend and Brian's two daughters.[4] This discovery was made by Kay Gilmer, a publicist employed by Landy in March 1990. She phoned Gary Usher to explain why his messages were not being returned, to which Usher warned: "If Landy knows that you're calling me, he'd kill you. He'd literally kill you."[32] Gilmer left her job two weeks later, taking expired drug bottles as well as names, phone numbers, and bank account information that she later turned over to the California Board of Medical Quality Assurance.[32]

Aided by Gilmer's findings,[32] Brian's cousin Stan Love filed unsuccessfully for conservatorship on May 17, 1990.[20] A press conference with Stan at the lectern featured an unexpected appearance from Brian. While reading from a piece of paper, Brian was given a microphone and said: "I have heard of the charges made by Stan Love, and I think they are outrageous, which means they are out of the ballpark ... I feel great."[33] Audree, Carl, Carnie, and Wendy Wilson then contested Landy's control of Brian, pursuing legal action on May 7, 1991.[34] The ruling was finalized on February 3, 1992 when Landy was barred by court order from contacting Brian, leaving his affairs to the hands of conservator Jerome S. Billet.[35] In December 1992, Landy was fined $1,000 for violating the court order when he visited Brian in June for his birthday.[36]

Love & Mercy

Landy's treatment of Wilson in the 1980s was dramatized in the 2014 biographical film Love & Mercy, in which Landy is portrayed by Paul Giamatti. These events are told from the point of view of Wilson's then-girlfriend Melinda Ledbetter. Landy's son Evan disputed the film's accuracy, believing that his father was unfairly portrayed.[37] Mike Love commented that Evan's account was "very interesting because you get an intimate look at someone who was with Brian every day for a few years".[38] Although he had not watched the film, he also said that it overstated Ledbetter's role in stopping the treatment.[39]

Screenwriter Oren Moverman stated that virtually everything in the 1980s portions was sourced from conversations he had with Ledbetter. He felt that Landy was the most difficult character to write for, "even though many things that he says in the movie I actually have recording of, in real life he was a cartoon and in real life he was so over the top."[40] Giamatti said he prepared for the role by meeting Landy's early career acquaintances and listening to hours of tapes where "he'd just keep talking and talking, in these completely huge paragraphs. They were brilliant-sounding, but if you dug into them they didn't make much sense."[41]

Personal life and death

Landy had one son in the early 1960s,[3] Evan Landy.[37][42]

After the 1990s, Landy continued a psychotherapeutic practice with licensure in New Mexico and Hawaii up until his death. He died, aged 71, on March 22, 2006 in Honolulu, Hawaii,[4][43] of pneumonia while suffering from lung cancer.[36]

Legacy

—Brian Wilson discussing Landy in a 2002 interview[44]

In 1995, music producer Don Was commented that Wilson was "so different from his public image as a drug burnout or of someone catatonic and propped up by a greedy psychologist. ... I knew Landy. I was around for the tail end of it, and I saw some gray in there; he wasn't just this evil guy who took over Brian."[45]

When asked what his reaction to Landy's death had been, Wilson responded: "I was devastated."[46] In 2015, Wilson reflected, "I thought he was my friend, but he was a very fucked-up man,"[47] and also, "I still feel that there was benefit. I try to overlook the bad stuff, and be thankful for what he taught me."[48]

References

- Gaines 1986, pp. 287, 290–291, 294, 338–341, 355; Carlin 2006, p. 273

- Carlin, Peter Ames (April 1, 2006). "Obituaries: Eugene Landy". The Independent. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012.

- Spiller, Nancy (July 26, 1988). "Bad Vibrations". The Los Angeles Times.

- "Obituary: Eugene Landy". The Telegraph. March 31, 2006. Archived from the original on February 25, 2008.

- Felton, David (November 4, 1976). "The Healing of Brother Brian". Rolling Stone.

- Klosterman, Chuck (December 31, 2006). "Off-Key: Syd Barrett | b. 1946; Eugene Landy | b. 1934". The New York Times.

Landy's method of treatment (a system he called "milieu therapy") was extremely aggressive and adversarial; he threw water on the musician to get him out of bed. ...

- Goldberg, Michael (August 11, 1988). Mirror. "God Only Knows". Rolling Stone.

- Wilkinson, Tracy (April 1, 1989). "Beach Boy Brian Wilson's Psychologist Loses License". The Los Angeles Times.

- Corsini 1981, p. 876.

- Carlin 2006, pp. 198–199.

- Badman 2004, p. 358.

- Goldberg, Michael (June 7, 1984). "Dennis Wilson: The Beach Boy Who Went Overboard". Rolling Stone.

- White, Timothy (May 1977). "Beach Men: We Can Go Our Own Way". Crawdaddy!: 64.

- Carlin 2006, pp. 243–244.

- White, Timothy (June 26, 1988). "BACK FROM THE BOTTOM". The New York Times.

- Carlin 2006, pp. 244, 256.

- Carlin 2006, p. 257.

- Fine, Jason (July 8, 1999). "Brian Wilson's Summer Plans". Rolling Stone.

- Mason, Anthony (July 19, 2015). "Brian Wilson's summer of milestones". CBS News.

- Hilburn, Robert (October 13, 1991). "Landy's Account of the Wilson Partnership". The Los Angeles Times.

- Stereogum (December 3, 2007). "Brian Wilson's Psychotic Surf Rap". Stereogum.

- Herrera, Dave (July 10, 2015). "A Q&A with Brian Wilson". Las Vegas Review Journal.

- Love 2016, pp. 333–334.

- Heller, Karen (October 23, 1991). "A Beach Boy's Blues For Brian Wilson, The Days Of "Fun, Fun, Fun" Have Ebbed. Although He Has A New Book, He's Also Involved in Several Lawsuits. "drugs," He Says, "put A Gash in My Mind."". The Philadelphia Inquirer.

- Carlin 2006, pp. 63, 272–273.

- Griffin, Gil (July 29, 1995). "Brian Wilson's Mom Sues Her Son's Publisher; Claims Libel". Billboard. 107 (30): 10, 32. ISSN 0006-2510.

- Love 2016, p. 367.

- Greenblatt, Mike (January 30, 2015). "Perception is reality for singer-songwriter P.F. Sloan". Goldmine.

- Ragogna, Mike (July 23, 2014). "From Eve of Destruction to Already Gone: Conversations with Jack Tempchin and P.F. Sloan, Plus a Godsmack Track". The Huffington Post.

- Carlin 2006, p. 271.

- Carlin 2006, p. 272.

- Love 2016, pp. 345–349.

- Love 2016, p. 343.

- Badman 2004, p. 375.

- Carlin 2006, p. 273.

- Fox, Margalit (March 30, 2006). "Eugene Landy, Therapist to Beach Boys' Leader, Dies at 71". The New York Times.

- Whitall, Susan (June 29, 2015). "Brian Wilson talks about 'Love & Mercy,' concert tour". The Detroit News. Archived from the original on August 5, 2015.

- Gillette, Sam (June 10, 2015). "Mike Love of Beach Boys on Love & Mercy: 'Poor Brian, He's Had a Rough, Rough Time'". Bedford and Bowery. Archived from the original on July 3, 2015.

- Kerns, William (March 5, 2016). "Kerns: Love providing 'Good Vibrations' as original Beach Boy". Archived from the original on March 13, 2016.

- Weintraub, Steve (June 6, 2015). "LOVE & MERCY Screenwriter Oren Moverman on Brian Wilson's Mythology, Fact vs. Fiction, and More". Collider. Archived from the original on June 7, 2015.

- Zeitchik, Steven (April 24, 2015). "Brian Wilson biopic 'Love & Mercy' a complex venture for Cusack, Giamatti". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 25, 2015.

- Gaines 1986, p. 342.

- Doyle, Patrick (September 9, 2009). "Celebrity Death Doctors: Michael Jackson's Personal Physician Dr. Conrad Murray and Seven Other Notorious Real-Life Procurers". The Village Voice.

- Kottler, Jeffrey A. (2005). Divine Madness: Ten Stories of Creative Struggle. John Wiley & Sons. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-7879-8232-4.

- Newman, Melinda (August 5, 1995). "Wilson bio "made for these times"". Billboard. 107 (31): 7, 94. ISSN 0006-2510.

- Powell, Alison (June 15, 2008). "Brian Wilson: a Beach Boy's own story". The Telegraph. United Kingdom.

- Fine, Jason (July 2, 2015). "Brian Wilson's Better Days". Rolling Stone (1238).

- Phull, Hardeep (June 4, 2015). "How one quack doctor almost destroyed Brian Wilson's career". New York Post.

Bibliography

- Badman, Keith (2004). The Beach Boys: The Definitive Diary of America's Greatest Band, on Stage and in the Studio. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-818-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carlin, Peter Ames (2006). Catch a Wave: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Beach Boys' Brian Wilson. Rodale. ISBN 978-1-59486-320-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Corsini, Raymond J. (1981). Handbook of Innovative Psychotherapies. New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-06229-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gaines, Steven (1986). Heroes and Villains: The True Story of The Beach Boys. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80647-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Love, Mike (2016). Good Vibrations: My Life as a Beach Boy. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-698-40886-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- McParland, Stephen J. (1991). The Wilson Project. Berlot. ISBN 978-2-9544834-0-5.