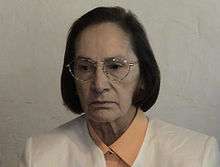

Esperanza Brito de Martí

Esperanza Brito de Martí (1932 - 16 August 2007) was a Mexican journalist, feminist and reproductive rights activist. She was the director of Fem magazine for nearly 30 years and wrote as a correspondent for several newspapers and magazines. Her journalism was honored with the National Journalism Prize "Juan Ignacio Castorena y Visúa". She was an advocate for both contraception and abortion rights. Through her many activities, she co-founded the Coalición de Mujeres Feministas, the Movimiento Nacional de Mujeres and pressed for the founding of the first Rape Crisis and Guidance Center (Coapevi), first agency for dealing specifically with sexual crimes, first Center for Domestic and Sexual Violence (NOTIFY). In 1998, the first Center for Support of Women which was named after her was opened.

Esperanza Brito de Martí | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Esperanza Brito Moreno 1932 |

| Died | 16 August 2007 Mexico City, Mexico |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Occupation | journalist, feminist, reproductive rights activist |

| Years active | 1963-2005 |

Biography

Esperanza Brito Moreno was born in 1932 in Mexico City[1] to the rector of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, Rodulfo Brito Foucher and the writer and feminist[2] Esperanza Moreno.[3]

Brito married at nineteen and raised six children before questioning her life choices. In 1963, she decided to pursue a journalism career and began writing for the society page of Novedades.[4] In 1966, she read an article her mother had written for El Universal entitled 'Yo, sí soy feminista' (I, yes I, am a feminist) and came to the realization that feminism was not about being "against men, but against the oppressive and discriminatory system(s) that makes all women inferior beings to all men".[2] The following year, she co-founded the organization Coalición de Mujeres Feministas (Coalition of Women Feminists).[5] The woman began to analyze the Mexican legal codes for discrimination, so that they could present facts and prove that many of the federal programs had policies that ran counter to equality, including those related to family and parenthood.[2] Characterized as Betty Friedan's "analog",[6] Brito cofounded the Coalición de Mujeres Feministas in 1967.

In 1970, she moved to Novedades editorial page for a year and in 1971 took a job at Siempre, which lasted three years.1972 Brito and 23 other women founded[4] the Movimiento Nacional de Mujeres (National Movement of Women), for which she became president[5] and participated in the first protests against the death of women by illegal abortions.[3] She won the National Journalism Prize "Juan Ignacio Castorena y Visúa" in 1974[4] for a piece analyzing women activists entitled, "Cuando la Mujer Mexicana Quiere, Puede" (When Mexican Women Want, They Can Get). At the United Nations first World Conference on Women, held in Mexico City, in 1975, Brtio came in contact for the first time with radical feminist ideology.[2] These activists were hoping for gains in contraception and a woman's right to make her own body choices. Pressed by activists, president Luis Echeverría convened the Interdisciplinary Group for the Study of Abortion, which included anthropologists, attorneys, clergy (Catholic, Jewish and Protestant), demographers, economists, philosophers, physicians, and psychologists. Their findings, contained in a report issued in 1976, which the Congress never passed nor implemented, were that criminalization of voluntary abortion should cease and that abortion services should be included in the government health package.[7] The report also highlighted the need for sexual education as early as primary school; information about contraception from high school forward; access to contraception; rejection of forced sterilization; and the rejection of abortion as a population control system. Brito and her colleagues pushed for all of these demands to be met.[2]

She changed jobs around this time and worked at the Almanac of Mexico from 1977 to 1984 with her son, Fernando Martí, who was also a journalist.[5] Simultaneously, she began publishing in a variety of newspapers and magazines, including El Universal and worked as the editorial coordinator for Publicaciones Continentales de México (Continental Publications of Mexico), which produced the Mexican versions of Cosmopolitan, Good Housekeeping and Vanity Fair.[4] She led a protest on the steps of the Chamber of Deputies in 1982 demanding that motherhood be free and voluntary and that women had the right to live free of violence and discrimination and with equal political and civil rights.[3] In 1987,[2] she began directing Fem magazine, which had been founded by Alaíde Foppa, where she remained for the next 21 years and then directed the electronic version for another two years.[3] In 1988 she helped found the first Rape Crisis and Guidance Center (Coapevi) and in 1989 helped open the first agency which specialized in dealing with sexual crimes. In 1990, Brito was instrumental in pushing for the creation the first Center for Domestic and Sexual Violence (NOTIFY)[1] and passage of the first laws on sexual assault.[4]

In 1996, she took over, from her mother, the direction of the Child Nutritional Rehabilitation Centre organized by Elena Arizmendi Mejia's under the La Cruz Blanca,[3] continuing her work at Fem.[1] Two years later, in 1998, Brito's work was publicly acknowledged when the first Center for Support of Women opened in Mexico City bearing her name.[2] In 2005, she retired from Fem.[1]

Esperanza Brito de Martí died in Mexico City on 16 August 2007.[1]

References

- Cervantes Pérez, Erika (29 May 2012). "Esperanza Brito de Martí" (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: Cimac Noticias. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- Scholtys, Britta (July 1998). "Hope Brito" (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: Diario Libertad. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- Lovera, Sara (15 August 2007). "Murió Esperanza Brito, emblemática feminista" (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: Notiese. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- Lovera, Sara (16 August 2007). "Murió Esperanza Brito, feminista mexicana". Mujeres Net (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: Mujeres Net. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- Musacchio, Humberto (2007). "Murió Esperanza Brito de Martí" (in Spanish). Acapulco, Mexico: El Sur Acapulco. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- Rodgers, Raman & Reimitz 2013, p. 244.

- Lamas, Marta (1 November 1997). "The feminist movement and the development of political discourse on voluntary motherhood in Mexico". Reproductive Health Matters. 5 (10): 58–67. doi:10.1016/s0968-8080(97)90086-0. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

Bibliography

- Rodgers, Daniel T.; Raman, Bhavani; Reimitz, Helmut (8 December 2013). Cultures in Motion. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-4989-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)