Esper Ukhtomsky

Prince Esper Esperovich Ukhtomsky, Эспер Эсперович Ухтомский (26 August [O.S. 14 August] 1861 – 26 November 1921) was a poet, publisher and Oriental enthusiast in late Tsarist Russia. He was a close confidant of Tsar Nicholas II and accompanied him whilst he was Tsesarevich on his Grand tour to the East.

Esper Esperovich Ukhtomsky | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 26 August 1861 |

| Died | 26 November 1921 Detskoye Selo, Russia |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Occupation | Diplomat Courtier Poet |

| Spouse(s) | Maria Vasilievna Vasilyeva |

| Children | Dy Esperovich Ukhtomsky |

| Parent(s) | Esper Alekseevich Ukhtomsky Yevgeniya Alekseevna Greig |

Family

Ukhtomsky was born in 1861 near the Imperial summer retreat at Oranienbaum. His family traced their lineage to the Rurik Dynasty, and had been moderately prominent boyars in the Muscovite period. His father, Esper Alekseevich Ukhtomsky had been an officer in the Imperial Russian Navy during the Crimean War, and had been present at the siege of Sevastopol. He went on to establish a commercial steamship company with routes from Saint Petersburg to India and China. He died when the young Esper was seven. His mother, Yevgeniya (Dzhenni) Alekseevna Greig, was descended from the Greigs, a long line of admirals of Scottish origin, notably Samuel and Alexey Greig. One of Esper's relations, Pavel Petrovich Ukhtomsky, served as a vice-admiral of the Pacific Squadron in the Russo-Japanese War.

Early life

Esper was privately educated by tutors during his early years, and travelled to Europe on numerous occasions with his parents. He received his secondary education at a Gymnasium and went on to read philosophy and literature at the University of Saint Petersburg. He graduated in 1884, winning a silver medal for his master's thesis 'A Historical and Critical Survey of the Study of Free Will.' It was during this period that he began to dabble in poetry, which was published in a number of Russian periodicals.

He got a job in the Interior Ministry's Department of Foreign Creeds, and travelled to Eastern Siberia to report on the Buryats. He then went on to travel as far as Mongolia and China, reporting on frictions between Russian Orthodoxy and Buddhism. He also took note of the effects of Alexander III's policies of Russification. He would later write reports criticising the overzealousness of the local Orthodox clergy in attempting to win converts, and expressed tolerant views regarding Russia's non-Orthodox faiths.

Ukhtomsky was also passionate about Oriental culture and arts. He was the standalone figure in Russian establishment to proclaim himself Buddhist.[1] During his journeys he amassed a large collection of Chinese and Tibetan art, that eventually numbered over 2,000 pieces. They were displayed in the Alexander III Museum in Moscow (now the State Historical Museum), and were also exhibited at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900, earning Ukhtomsky a gold medal.

Rising fame and the Grand Tour

Ukhtomsky's activities attracted the attention of the Oriental establishment active in Saint Petersburg, and he was elected to the Imperial Geographical Society and began to advise the Foreign Ministry on East Asian matters. His expertise in Eastern matters and his high social standing led to him being selected to accompany the Tsesarevich Nicholas on his Grand tour to the East. Nicholas took a liking to Esper Ukhtomsky, writing to his sister that "the little Ukhtomskii...is such a jolly fellow".[2] After returning to Russia in 1891, Ukhtomsky was appointed to the role of court chamberlain, and served on the Siberian Railway Committee. He also began work on his account of the grand tour, entitled Travels in the East of Nicholas II.

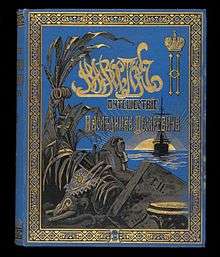

The book was written in close consultation with Nicholas II, who personally approved each chapter. It took six years to complete, and was published in three volumes between 1893 and 1897 by Brockhaus, in Leipzig. Despite being expensive at 35 roubles, it still ran to four editions. Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna bought several thousand copies for various government ministries and departments, and a cheaper edition was subsequently printed. The work was translated into English, French, German and Chinese, with a copy being presented to the Chinese Emperor and Empress in 1899 by the Russian envoy.[3]

Ukhtomsky became a close confidante and adviser to the Tsar on matters of Eastern policy and was made editor of the Saint Petersburg Gazette in 1895. He used the paper to promote and emphasise the importance of Russian expansionism in the East as a basis of Russian foreign policy, an approach which sometimes drew fire from right-wing colleagues, and those advocating Westernisation. He continued to converse with Nicholas and used his position to advocate Russian intervention in East Asia, but by 1900 Ukhtomsky's influence was waning.

China and the Trans-Siberian Railway

As chairman of the Russo-Chinese Bank, Ukhtomsky was involved in negotiations with the Chinese regarding the route of the Trans-Siberian Railway, and escorted Chinese statesman Li Hongzhang for negotiations in St Petersburg in 1896.[4] The Russians were keen to secure a route through Manchuria. Ukhtomsky travelled to the Chinese court in 1897 and presented gifts to the emperor, as well as large bribes to officials; he later became the chairman of the Chinese Eastern Railway.[4]

When the Boxer Rebellion broke out in 1900, Ukhtomsky was dispatched to Peking to offer Russian support against the Western powers who might seek to take advantage of the situation and push into China. By the time he arrived in Shanghai, he was too late. The Western powers had lifted the Siege of Peking a month earlier and had occupied the city. Despite offering to represent the Chinese to the occupying armies he was recalled to Saint Petersburg.

Decline and legacy

Following the dismissal of his patron, Sergei Witte from the government, from 1903 Ukhtomsky found himself increasingly isolated. He continued to editorialise about the East for a few more years, taking an especially assertive viewpoint that the Russia should continue the war against Japan until it achieved complete victory.[4] Although he remained active within Saint Petersburg's orientalist community, he mainly concerned himself with editing his paper, which he did until the fall of the Romanov dynasty in 1917.

He would remain an important social figure far beyond Eastern affairs and his editor's duties, becoming a household name in the house of Leo Tolstoy, and through him establishing ties with Doukhobor leader Peter Vasilevich Verigin. He would publish the works of his University teacher Vladimir Solovyov, and after the latter's death, became one of key figures of Solovyov Society that would among other issues discuss the necessity of equal rights for repressed Doukhobors and Molokans, Jewish and Armenian people.

He survived the revolution, and having lost his son in the First World War had to support himself and his three grandchildren by working in a number of Saint Petersburg's museums and libraries, as well as by odd translation jobs before dying in 1921.

His collection of art was taken from him by the Bolsheviks in 1917 and now forms a significant part of the East Asian holdings at the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, as well as some other museums.

Ukhtomsky is primarily remembered for his account of Nicholas's Grand Tour and for his role in promoting Eastern affairs in Russian society in the later years of the Russian empire.

Family

Ukhtomsky married Maria Vasilievna Vasilyeva, the daughter of a peasant. They had one son, Dy Esperovich Ukhtomsky (1886 - 1918), who became a Fellow of the Russian Museum in 1908. Dy Ukhtomsky married Princess Natalia Dimitrieva Tserteleva (1892 - 1942), daughter of philosopher and poet Prince Dimitri Nikolaevich Tsertelev (30 June 1852 - 15 August 1911) and had three children: Dmitri, Alexei (1913 - 1954), and Marianne (1917 - 1924). Dmitri (1912 - 1993) served as a foreign intelligence officer in Iran during World War II and later became a noted photographer and photojournalist.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Esper Ukhtomsky. |

- Johnson, K. Paul. Initiates of theosophical masters.(SUNY series in Western esoteric traditions/Suny Series in Political Party Development). SUNY Press, 1995. ISBN 0-7914-2555-X, 978-0-7914-2555-8 page 125

- Nicholas Aleksandrovich to Grand Duchess Ksenia, letter, Nov. 4, 1890, GARF, f. 662, o. 1, d. 186, l. 41.

- Schimmelpinninck, p. 49

- Kowner, Rotem (2006). Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War. The Scarecrow Press. p. 403. ISBN 0-8108-4927-5.

- Prince E. Ukhtomskii, Travels in the East of Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia When Cesarewitch 1890–1891, 2 vols., (London, 1896), II.

- E. Sarkisyanz, Russian Attitudes towards Asia in 'Russian Review', Vol. 13., No. 4 (Oct., 1954), pp. 245–254.

- D. Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, Toward the Rising Sun: Russian Ideologies of Empire and the Path to War with Japan, (Illinois, 2001)

- Khamaganova E.A. Princes Esper and Dii Ukhtomsky and Their Contribution to the Study of Buddhist Culture (Tibet, Mongolia and Russia) // Tibet, Past and Present. Tibetan Studies. PIATS. 2000: Proceedings of the Ninth Seminar of the International Tibetan Studies. Leiden, 2000. Brill, Leiden-Boston-Koln, 2002, pp. 307-326.