Ertuğrul

Ertuğrul or Ertuğrul Ghazi (Ottoman Turkish: ارطغرل, romanized: Erṭoġrıl, died c. 1280)[5] was the father of Osman I.[6] Little is known about Ertuğrul's life. According to Ottoman tradition, he was the son of Suleyman Shah, the leader of the Kayı tribe (a claim which has come under criticism from many historians[nb 1]) of Oghuz Turks, who fled from western Central Asia to Anatolia to escape the Mongol conquests, but he may instead have been the son of Gündüz Alp.[3][8] According to this legend, after the death of his father, Ertuğrul and his followers entered the service of the Sultanate of Rum, for which he was rewarded with dominion over the town of Söğüt on the frontier with the Byzantine Empire.[5] This set off the chain of events that would ultimately lead to the founding of the Ottoman Empire.

| Ertuğrul ارطغرل | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghazi | |||||

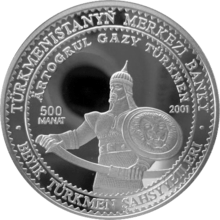

Ertuğrul on a 2001 Turkmen coin | |||||

| Uç bey of the Sultanate of Rum | |||||

| Reign | Unknown – c. 1280 | ||||

| Predecessor | Office established | ||||

| Successor | Osman I | ||||

| Born | Unknown | ||||

| Died | c. 1280 Söğüt, Sultanate of Rum | ||||

| Burial | Tomb of Ertuğrul Gazi, Söğüt, Bilecik Province | ||||

| Spouse | Halime Hatun (disputed) | ||||

| Issue | Osman I 2 other sons[1][2] | ||||

| |||||

| Father | Suleyman Shah or Gündüz Alp[3][4] | ||||

| Mother | Hayme Ana[3] | ||||

Biography

Nothing is known with certainty about Ertuğrul's life, other than that he was the father of Osman; historians are thus forced to rely upon stories written about him by the Ottomans more than a century later, which are of questionable accuracy.[9][10] An undated coin, supposedly from the time of Osman, with the text "Minted by Osman son of Ertuğrul", suggests that Ertuğrul was a historical figure.[6]:31 Another coin reads "Osman bin Ertuğrul bin Gündüz Alp",[3][4] though Ertuğrul is traditionally considered the son of Suleyman Shah.[8]

In Enveri's Düsturname (1465) and Karamani Mehmet Pasha's chronicle (before 1481), Suleyman Shah replaces Gündüz Alp as Ertugrul's father. After Ottoman historian Aşıkpaşazade's chronicles, the Suleyman Shah version became the official one.[11] According to many turkish sources, Ertuğrul had three brothers named; Sungur-tekin, Gündoğdu and Dündar.[2] After the death of their father, Ertuğrul with his mother Hayme Hatun, Dündar and his followers from the Kayı Tribe migrated west into Anatolia and entered the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum, leaving his two brothers who took their clans towards the east.[12][13][14] In this way, Kayı Tribe was divided into two parts. According to these later traditions, Ertuğrul was chief of his Kayı Tribe.[5] As a result of his assistance to the Seljuks against the Byzantines, Ertuğrul was granted lands in Karaca Dağ, a mountainous area near Angora (now Ankara), by Kayqubad I, the Seljuk Sultan of Rum. One account indicates that the Seljuk leader's rationale for granting Ertuğrul land was for Ertuğrul to repel any hostile incursion from the Byzantines or other adversary.[15] Later, he received the village of Söğüt which he conquered together with the surrounding lands. That village, where he later died, became the Ottoman capital under his son, Osman I.[4] Osman's mother has been referred to as Halime Hatun in later myths, and there is a grave outside the Ertuğrul Gâzi Tomb which bears the name, but it is disputed.[16][17]

According to many sources, he had two other sons in addition to Osman: Saru-Batu (Savci) Bey[18][4] and Gündüz Bey.[1][11][19] Like his son, Osman, and their descendants, Ertuğrul is often referred to as a Ghazi, a heroic champion fighter for the cause of Islam.[20]

Legacy

A tomb and mosque dedicated to Ertuğrul is said to have been built by Osman I at Söğüt, but due to several rebuildings nothing certain can be said about the origin of these structures. The current mausoleum was built by sultan Abdul Hamid II in the late 19th century. The town of Söğüt celebrates an annual festival to the memory of the early Osmans.[6]:37[21]

The Ottoman frigate Ertuğrul, launched in 1863, was named after him. The Ertuğrul Gazi Mosque in Ashgabat, Turkmenistan, completed in 1998, is also named in his honor. It was established by the Turkish government as a symbol of the link between Turkey and Turkmenistan.[22]

The last will of Ertugrul Gazi to his son, Osman Gazi, in front of his tomb reads:

Lo, son! Offend me, offend not Shaykh Edebali. He is the light of our clan. His balance does not err by a dirham. Oppose me, oppose him not. If you oppose me, I will be sad and hurt. If you oppose him, my eyes will not look at you, even if they look they will not see. Our words are not for Edebali but for you dear. Consider what I have said my last will.

— Ertuğrul Gazi

In fiction

Ertugrul has been portrayed in the Turkish television series Kuruluş/Osmancık (1988), adapted from a novel by the same name,[23] and Diriliş: Ertuğrul (2014).[24]

Notes

- who argue either that the Kayı genealogy was fabricated in the fifteenth century, or that there is otherwise insufficient evidence to believe in it.[7]

References

- Rosenwein, Barbara H. (2018). Reading the Middle Ages, Volume II: From c.900 to c.1500, Third Edition. University of Toronto Press. p. 455. ISBN 978-1-4426-3680-4. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Âşıkpaşazâde, History of Âşıkpaşazâde; & İnalcık, Halil (2007). "Osmanlı Beyliği'nin Kurucusu Osman Beg". Belleten (in Turkish). Ankara. 7: 483, 488–490.

- Akgunduz, Ahmed; Ozturk, Said (2011). Ottoman History - Misperceptions and Truths. IUR Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-90-90-26108-9.

- "ERTUĞRUL GAZİ at TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi Site - Published in the 11th Volume of İslâm Ansiklopedisi in 1995". islamansiklopedisi.org.tr (in Turkish). Istanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Shaw, Stanford J.; Shaw, Ezel Kural (29 October 1976). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey: Volume 1, Empire of the Gazis: The Rise and Decline of the Ottoman Empire 1280-1808. Cambridge University Press. p. 13. Retrieved 14 June 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- Finkel, Caroline (2012). Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire 1300-1923. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 9781848547858. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

....suggests that Ertuğrul was a historical personage

- Kafadar, Cemal (1995). Between Two Worlds: The Construction of the Ottoman State. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-520-20600-7.

That they hailed from the Kayı branch of the Oğuz confederacy seems to be a creative "rediscovery" in the genealogical concoction of the fifteenth century. It is missing not only in Ahmedi but also, and more importantly, in the Yahşi Fakih-Aşıkpaşazade narrative, which gives its own version of an elaborate genealogical family tree going back to Noah. If there was a particularly significant claim to Kayı lineage, it is hard to imagine that Yahşi Fakih would not have heard of it

- Lowry, Heath (2003). The Nature of the Early Ottoman State. SUNY Press. p. 78. ISBN 0-7914-5636-6.

Based on these charters, all of which were drawn up between 1324 and 1360 (almost one hundred fifty years prior to the emergence of the Ottoman dynastic myth identifying them as members of the Kayı branch of the Oguz federation of Turkish tribes), we may posit that...

- Shaw, Stanford (1976). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Cambridge University Press. p. 13.

The problem of Ottoman origins has preoccupied students of history, but because of both the absence of contemporary source materials and conflicting accounts written subsequent to the events there seems to be no basis for a definitive statement.

- Lowry, Heath (2003). The Nature of the Early Ottoman State. SUNY Press. p. 78. ISBN 0-7914-5636-6.

- Kermeli, Eugenia (2009). "Osman I". In Ágoston, Gábor; Bruce Masters (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. p. 444.

Reliable information regarding Osman is scarce. His birth date is unknown and his symbolic significance as the father of the dynasty has encouraged the development of mythic tales regarding the ruler’s life and origins

- Lindner, Rudi P. (1983). Nomads and Ottomans in Medieval Anatolia. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 21.

No source provides a firm and factual recounting of the deeds of Osman's father.

- Kafadar, Cemal (1995). Between Two Worlds: The Construction of the Ottoman State. pp. 60, 122.

- The Cambridge History of Turkey. Cambridge University Press. 2009. p. 118. ISBN 9780521620932. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- Lindner, Rudi Paul (2007). Explorations in Ottoman Prehistory. University of Michigan Press. pp. 20, 29. ISBN 0-472-09507-2. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- Heywood, Colin; Imber, Colin (1994). Sammlung (Snippet View). Isis Press, Original from University of Michigan. p. 160. ISBN 978-97-54-28063-0. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- Demirbağ, Fehmi. IYI: Ertuğrul Ve İyilik Takımı (in Turkish). Akis Kitap. p. 35. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- Cengiz, Oğuzhan (2015). ERTUĞRUL GAZİ KURULUŞ (in Turkish). Bilgeoğuz Yayinlari. p. 170. ISBN 978-60-59-96018-2. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- Ali Anooshahr, The Ghazi Sultans and the Frontiers of Islam, pg. 157

- Güler, Turgut. Mahzun Hududlar Çağlayan Sular (in Turkish). Ötüken Neşriyat A.Ş. ISBN 978-605-155-702-1. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

In the tomb’s garden, there is a grave belonging to Ertuğrul’s wife, Halime Hâtûn. However, here there must be some information mistakes. The name of the esteemed woman who was the wife of Ertuğrul Gâzi and mother of Osman Gâzi is “Hayme Ana”, and her grave is in the Çarşamba village of Kütahya’s Domaniç district. Sultan Abdülhamid II, who had the Ertuğrul Gâzi Tomb repaired, also had the Hayme Ana Tomb as good as rebuilt in the same years. Therefore, the grave in Söğüt said to be of Halime Hâtûn, must belong to another deceased.

- Lowry, Heath W. (1 February 2012). "Nature of the Early Ottoman State, The". SUNY Press. p. 153. Retrieved 26 December 2017 – via Google Books.

- İslam Tarihi ve Medeniyeti - 12: Osmanlılar-1 (in Turkish). Istanbul. 2018. ISBN 978-605-2375-38-9. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Manav, Bekir (2017). Ertuğrul Gazi (in Turkish). Istanbul. p. 88. ISBN 978-605-2394-23-6. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Southeastern Europe under Ottoman rule, 1354-1804, By Peter F. Sugar , pg.14

- Deringil, Selim (2004). The Well-protected Domains: Ideology and the Legitimation of Power in the Ottoman Empire 1876-1909. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 31-32. ISBN 978-1-86064-472-6. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- Rizvi, Kishwar (2015). The Transnational Mosque: Architecture and Historical Memory in the Contemporary Middle East. University of North Carolina Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-4696-2117-3. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- KUTAY, UĞUR (10 February 2020). "Osmancık'tan ve Osman'a". BirGün (in Turkish). Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Haider, Sadaf (15 October 2019). "What is Dirilis Ertugrul and why does Imran Khan want Pakistanis to watch it?". Dawn. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ertuğrul Gazi. |

Bibliography

- Ágoston, Gábor; Bruce Masters, eds. (2009). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-6259-1.

- Lindner, Rudi P. (1983). Nomads and Ottomans in Medieval Anatolia. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-933070-12-8.

- Kafadar, Cemal (1995). Between Two Worlds: The Construction of the Ottoman State. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20600-7.