Ernie Barnes

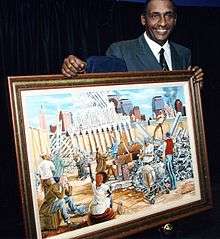

Ernest Eugene Barnes Jr. (July 15, 1938 – April 27, 2009) was an American artist, well known for his unique style of elongation and movement. He was also a professional football player, actor and author.

Ernie Barnes | |

|---|---|

Barnes in 1974 | |

| Born | Ernest Eugene Barnes Jr. July 15, 1938 |

| Died | April 27, 2009 (aged 70) Los Angeles, California, US |

| Occupation | American artist, football player, actor |

| Height | 6 ft 3 in (1.91 m) |

Early life

Childhood

Ernest Barnes Jr. was born during the Jim Crow in "the bottom" community of Durham, North Carolina, near the Hayti District of the city. He had a younger brother, James (b. 1942), as well as a half-brother, Benjamin B. Rogers Jr. (1920–1970). Ernest Jr. was nicknamed "June". His father, Ernest E. Barnes Sr. ( –1966), worked as a shipping clerk for Liggett Myers Tobacco Company. His mother, Fannie Mae Geer (1905–2004), oversaw the household staff for a prominent Durham attorney and local Board of Education member, Frank L. Fuller Jr.

On days when Fannie allowed "June" (Barnes' nickname to family and childhood friends) to accompany her to work, Mr. Fuller encouraged him to peruse the art books and listen to classical music. The young Ernest was intrigued and captivated by the works of master artists. By the time Barnes entered the first grade, he was familiar with the works of such masters as Toulouse-Lautrec, Delacroix, Rubens and Michelangelo. When he entered junior high school, he could appreciate, as well as decode, many of the cherished masterpieces within the walls of mainstream museums – although it would be many more years before he was allowed entrance because of segregation.[1]

A self-described chubby and unathletic child, Barnes was taunted and bullied by classmates. He continually sought refuge in his sketchbooks, finding the less-traveled parts of campus away from other students. One day Ernest was drawing in his notebook in a quiet area of the school. He was discovered hiding there by the masonry teacher, Tommy Tucker, who was also the weightlifting coach and a former athlete. He was intrigued with Barnes' drawings, so he asked the aspiring artist about his grades and goals. Tucker shared his own experience of how bodybuilding improved his strength and outlook on life. That one encounter would begin Barnes' discipline and dedication that would permeate his life. In his senior year at Hillside High School, Barnes became the captain of the football team and state champion in the shot put.[2]

College education

Barnes attended racially segregated schools. In 1956 he graduated from Hillside High School with 26 athletic scholarship offers. Segregation prevented him from attending nearby Duke University or the University of North Carolina. His mother promised him a car if he lived at home so he attended the all-Black North Carolina College at Durham (formerly North Carolina College for Negroes, now North Carolina Central University). At North Carolina College he majored in art on a full athletic scholarship. His track coach was Dr. Leroy T. Walker.[1] Barnes played the football positions of tackle and center at NCC.

At age 18, on a college art class field trip to the newly desegregated North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh, Barnes inquired where he could find "paintings by Negro artists". The docent responded, "Your people don't express themselves that way".[3] 23 years later, in 1979, when Barnes returned to the museum for a solo exhibition, North Carolina Governor Jim Hunt attended.

In 1990 Barnes was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts by North Carolina Central University.[4]

In 1999 Barnes was bestowed "The University Award", the highest honor by the University of North Carolina Board of Governors.[4]

Professional football

Baltimore Colts (1959–60)

In December 1959 Barnes was drafted in the 10th round by the then-World Champion Baltimore Colts. He was originally selected in the 8th-round by the Washington Redskins,[5] who renounced the pick minutes after discovering he was a Negro.

Shortly after his 22nd birthday, while at the Colts training camp, Barnes was interviewed by N.P. Clark, sportswriter for the Baltimore News-Post newspaper. Until then Barnes was always known by his birth name, Ernest Barnes. But when Clark's article appeared on July 20, 1960, it referred to him as "Ernie Barnes," which changed his name and life forever.[6]

Titans of New York (1960)

Barnes was the last cut of the Colts' training camp. After Baltimore released Barnes, the newly formed Titans of New York immediately signed him because the team had first option on any player released within the league.[5]

Barnes loathed being on the Titans. He said, "(New York team organization) was a circus of ineptitude. The equipment was poor, the coaches not as knowledgeable as the ones in Baltimore. We were like a group of guys in the neighborhood who said let's pretend we're pros."[5]

After their seventh game on October 9, 1960 at Jeppesen Stadium, his teammate Howard Glenn died. Barnes asked for his release two days later. The cause of Glenn's death was reported as a broken neck. However, Barnes and other teammates have long attributed it to heatstroke.[1] In a later interview, Barnes said, "They never really said what he died of. (Coach) Sammy Baugh said he'd broken his neck in a game the Sunday before. But how could that be? How could he have hit in practice all week with a broken neck? What he died of, I think, was more like heat exhaustion. I told them I didn't want to play on a team like this."[5]

San Diego Chargers (1960–62)

Barnes decided to accept a previous offer from Coach Al Davis at the Los Angeles Chargers. Barnes joined their team at mid-season as a member of their taxi squad. The following season in 1961 the team moved to San Diego. It was there Barnes met teammate Jack Kemp, and the two men would share a very close lifelong friendship.

During the off-seasons with the Chargers, Barnes was program director at San Diego's Southeast YMCA working with parolees from the California Youth Authority.[1] He also worked as the Sports Editor for The Voice, a local San Diego newspaper, writing a weekly column called "A Matter of Sports."[7]

Barnes also illustrated several articles for San Diego Magazine during the off-seasons in 1962 and 1963.[8][9]

Barnes' first television interview as a professional football player and artist was in 1962 on The Regis Philbin Show on KGTV in San Diego. It was Philbin's first talk show. They would see each other again 45 years later when Philbin attended the tribute to Barnes in New York City.

Denver Broncos (1963–64)

Midway through Barnes' second season with the Chargers, he was cut after a series of injuries. He was then signed to the Denver Broncos.

Barnes was often fined by Denver Coach Jack Faulkner when caught sketching during team meetings.[1] One of the sketches that he was fined $100 for sold years later for $1000.[10]

Many times during breaks, Barnes would run off the field onto the sideline to give his offensive line coach Red Miller the scraps of paper of his sketches and notes.

"During a timeout you've got nothing to do – you're not talking – you're just trying to breathe, mostly. Nothing to take out that little pencil and write down what you saw. The shape of the linemen. The body language a defensive lineman would occupy... his posture... What I see when you pull. The reaction of the defense to your movement. The awareness of the lines within the movement, the pattern within the lines, the rhythm of movement. A couple of notes to me would denote an action... an image that I could instantly recreate in my mind. Some of those notes have been made into paintings. Quite a few, really."[11]

On Barnes' 1964 Denver Broncos Topps football card he is shown wearing jersey #55 although he never played in that number. His jersey was #62.

Barnes was called "Big Rembrandt" by his Denver teammates.[12] Coincidentally, Barnes and Rembrandt share the same birthday.

Canadian Football League

In 1965, after his second season with the Broncos, Barnes signed with the Saskatchewan Roughriders in Canada. In the final quarter of their last exhibition game, Barnes fractured his right foot, effectively ending his professional football career.

Retirement

Shortly after his final football game, Barnes went to the 1965 NFL owners meeting in Houston in hopes of becoming the league's official artist. There he was introduced to New York Jets owner Sonny Werblin, who was intrigued by Barnes and his art. He paid for Barnes to bring his paintings to New York City. Later they met at a gallery and unbeknownst to Barnes, three art critics were there to evaluate his paintings. They told Werblin that Barnes was "the most expressive painter of sports since George Bellows."[1]

In what was one of the most unusual posts in the history of the NFL, Werblin retained Barnes as a salaried player, but positioned him in front of the canvas, rather than on the football field. Werblin told Barnes, "You have more value to the country as an artist than as a football player."[13]

Barnes' November 1966 debut solo exhibition, hosted by Werblin at the Grand Central Art Galleries in New York City was critically acclaimed and all the paintings sold.[14][15]

In 1971 Barnes wrote a series of essays (illustrated with his own drawings) in the Gridiron newspaper titled "I Hate the Game I Love" (with Neil Amdur).[16] These articles became the beginning manuscript of his autobiography, later-published in 1995 titled From Pads to Palette which chronicles his transition from professional football to his art career.

In 1993 Barnes was selected to the "Black College Football 100th Year All-Time Team" by the Sheridan Broadcasting Network.

Artwork

Barnes credits his college art instructor Ed Wilson for laying the foundation for his development as an artist.[17] Wilson was a sculptor who instructed Barnes to paint from his own life experiences. "He made me conscious of the fact that the artist who is useful to America is one who studies his own life and records it through the medium of art, manners and customs of his own experiences."[18]

All his life, Barnes was ambivalent about his football experience. In interviews and in personal appearances, Barnes said he hated the violence and the physical torment of the sport. However, his years as an athlete gave him unique, in-depth observations. "(Wilson) told me to pay attention to what my body felt like in movement. Within that elongation, there's a feeling. And attitude and expression. I hate to think had I not played sports what my work would look like."[19]

Barnes sold his first painting "Slow Dance" at age 21 in 1959 for $90 to Boston Celtic Sam Jones.[1] It was subsequently lost in a fire at Jones' home.

Numerous artists have been influenced by Barnes' art and unique style. Accordingly, several copyright infringement lawsuits have been settled and are currently pending.

Framing

Ernie Barnes framed his paintings with distressed wood in homage to his father. In his 1995 autobiography, Barnes wrote of his father: “... with so little education, he had worked so hard for us. His legacy to me was his effort, and that was plenty. He knew absolutely nothing about art.”[1]

Weeks before Ernie Barnes’ first solo art exhibition in 1966, he was at the family home in Durham as his father lay in the hospital after suffering a stroke. He noticed the usually well-maintained white picketed fence had gone untended since his father’s illness. Days later, Ernest E. Barnes Sr. died. “I placed a painting against the fence and stood away and had a look. I was startled at the marriage between the old wood fence and the painting. It was perfect. In tribute, Daddy’s fence would hug all my paintings in a prestigious New York gallery. That would have made him smile.”[1]

Eyes closed

A consistent and distinct feature in Barnes' work is the closed eyes of his subjects. "It was in 1971 when I conceived the idea of The Beauty of the Ghetto as an exhibition. And I showed it to some people who were Black to get a reaction. And from one (person) it was very negative. And when I began to express my points of view (to this) professional man, he resisted the notion. And as a result of his comments and his attitude I began to see, observe, how blind we are to one another's humanity. Blinded by a lot of things that have, perhaps, initiated feelings in that light. We don't see into the depths of our interconnection. The gifts, the strength and potential within other human beings. We stop at color quite often. So one of the things we have to be aware of is who we are in order to have the capacity to like others. But when you cannot visualize the offerings of another human being you're obviously not looking at the human being with open eyes."[20] "We look upon each other and decide immediately: This person is black, so he must be... This person lives in poverty, so he must be..."[11]

Jewish community influence

Moving to an all-Jewish neighborhood in Los Angeles known as the Fairfax District in 1971 was a major turning point in Barnes' life and art.

"Fairfax enlivened me to everyday life themes," he said, "and forced me to look at my life – the way I had grown up, the customs within my community versus the customs in the Jewish community. Their customs were documented, ours were not. Because we were so clueless that our own culture had value and because of the phrase 'Black is Beautiful' had just come into fashion, Black people were just starting to appreciate themselves as a people. But when it was said, 'I'm Black and I'm Proud,' I said, 'proud of what?' And that question of 'proud of what' led to a series of paintings that became “The Beauty of the Ghetto.'"

"The Beauty of the Ghetto" exhibition

In response to the 1960s "Black is beautiful" cultural movement and James Brown's 1968 "Say it Loud: I'm Black and I'm Proud" song, Barnes created The Beauty of the Ghetto exhibition of 35 paintings that toured major American cities from 1972 to 1979 hosted by dignitaries, professional athletes and celebrities.

Of this exhibition, Barnes said, "I am providing a pictorial background for an understanding into the aesthetics of black America. It is not a plea to people to continue to live there (in the ghetto) but for those who feel trapped, it is...a challenge of how beautiful life can be."[21]

When the exhibition was on view in 1974 at the Museum of African Art in Washington, DC, Rep. John Conyers stressed the important positive message of the exhibit in the Congressional Record.

Sports art

The Los Angeles Olympic Organizing Committee named Barnes "Sports Artist of the 1984 Olympic Games". LAOOC President Peter V. Ueberroth said Barnes and his art "captured the essence of the Olympics" and "portray the city's ethnic diversity, the power and emotion of sports competition, the singleness of purpose and hopes that go into the making of athletes the world over." Barnes was commissioned to create five Olympic-themed paintings and serve as an official Olympic spokesman to encourage inner city youth.[22][23]

1985: Barnes was named the first "Sports Artist of the Year" by the United States Sports Academy.[10]

1987: Barnes created Fastbreak, a commissioned painting of the World Champion Los Angeles Lakers basketball team that included Magic Johnson, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, James Worthy, Kurt Rambis and Michael Cooper.

1996: Carolina Panthers football team owners Rosalind and Jerry Richardson (Barnes' former Colts teammate) commissioned Barnes to create the large painting Victory in Overtime (approximately 7 ft. x 14 ft.). It was unveiled before the team's 1996 inaugural season and hangs permanently in the owner's suite at the stadium. Richardson and Barnes were Baltimore Colts teammates briefly in 1960.

1996: To commemorate their 50th anniversary in 1996, the National Basketball Association commissioned Barnes to create a painting with the theme, "Where we were, where we are, and where we are going." The painting, The Dream Unfolds hangs in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Massachusetts. A limited edition of lithographs were made, with the first 50 prints going to each of the NBA's 50th Anniversary All-Time Team.

2004: Barnes was named "America's Best Painter of Sports" by the American Sport Art Museum & Archives.[24]

Other notable sports commissions include paintings for the New Orleans Saints, Oakland Raiders and Boston Patriots football team owners.[25]

"The Bench" painting

Shortly after Barnes was drafted by the Baltimore Colts, Barnes was invited to see their Colts' NFL Championship Game vs. the New York Giants at Memorial Stadium in Maryland on December 27, 1959. The Colts won 31–16 and Barnes was filled with layers of emotion after watching the game from the Colts' bench. At age 21, he had just signed his football contract and met his new teammates Johnny Unitas, Jim Parker, Lenny Moore, Art Donovan, Gino Marchetti, Alan Ameche and "Big Daddy" Lipscomb.

After he returned home, without making any preliminary sketches, he went directly to a blank canvas to record his point of view. Using a palette knife, "painting in quick, direct movements hoping to capture the vision...before it evaporated," Barnes said, he created "The Bench" in less than an hour.[1] Throughout his life, The Bench remained in Barnes' possession, even taking it with him to all his football training camps and hiding it under his bed. It would be the only painting Barnes would never sell, despite many substantial offers, including a $25,000 bid at his first show in 1966.

In 2014, Barnes' wife Bernie presented The Bench painting to the Pro Football Hall of Fame for their permanent collection in Canton, Ohio.

"The Sugar Shack" painting

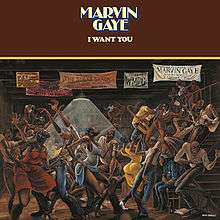

Barnes created the painting The Sugar Shack in 1971. It gained international exposure when it was used on the Good Times television series and on the 1976 Marvin Gaye album I Want You.

According to Barnes, he created the original version of The Sugar Shack after reflecting upon his childhood, during which he was not "able to go to a dance."[26] In a 2008 interview, Barnes said, "The Sugar Shack is a recall of a childhood experience. It was the first time my innocence met with the sins of dance. The painting transmits rhythm so the experience is re-created in the person viewing it. To show that African-Americans utilize rhythm as a way of resolving physical tension."[27]

The Sugar Shack has been known to art critics for embodying the style of art composition known as "Black Romantic," which, according to Natalie Hopkinson of The Washington Post, is the "visual-art equivalent of the Chitlin' circuit."[28]

When Barnes first created The Sugar Shack, he included his hometown radio station WSRC on a banner. (He incorrectly listed the frequency as 620, though it was actually 1410. Barnes confused what he used to hear WSRC's on-air personality Norfley Whitted saying "620 on your dial" when Whitted was at his former station WDNC in the early 1950s.)

After Marvin Gaye asked him for permission to use the painting as an album cover, Barnes then augmented the painting by adding references that allude to Gaye's album, including banners hanging from the ceiling to promote the album's singles.[28][29]

During the Motown 25: Yesterday, Today, Forever anniversary television special on March 25, 1983, tribute was paid to The Sugar Shack with a dance interpretation of the painting. It was also during this telecast that Michael Jackson introduced his famous "moonwalk" dance.

The original piece is currently owned by Jim and Jeannine Epstein, and is on display at the North Carolina Museum of History in Raleigh. A duplicate created by Barnes was created in 1976 on display at the California African American Museum (CAAM).[30]

Music album covers

Barnes' work appears on the following album covers:

- The Sugar Shack painting on Marvin Gaye's 1976 I Want You

- The Disco painting on self-titled 1978 Faith, Hope & Charity

- Donald Byrd and 125th Street, NYC painting on self-titled 1979 album

- Late Night DJ painting on Curtis Mayfield's 1980 Something to Believe In

- The Maestro painting on The Crusaders' 1984 Ghetto Blaster

- Head Over Heels painting on The Crusaders' 1986 The Good and Bad Times

- In Rapture painting on B.B. King's 2000 Making Love is Good For You

Other notable art and exhibitions

1992: In the wake of the 1992 Los Angeles riots, Mayor Tom Bradley used Barnes' painting Growth Through Limits as an inspirational billboard in the inner-city. Barnes contributed $1,000 to the winner of a slogan contest among the city's junior high school students that best represented the painting.[31][32]

1995: Barnes' work was included in the traveling group exhibition 20th Century Masterworks of African-American Artists II.[33]

1998: Barnes' painting The Advocate was donated to the North Carolina Central University School of Law by a private collector.[34] Barnes felt compelled to create the painting from his "concern with the just application of the law... the integrity of the legal process for all people, but especially those without resource or influence."[35]

2001: While watching the tragic events of 9/11, Barnes created the painting In Remembrance. It was formally unveiled at the Seattle Art Museum. It was later acquired on behalf of the City of Philadelphia and donated to its African American Museum. A limited number of giclée prints were sold with 100% of the proceeds going to the Hero Scholarship Fund, which provides college tuition and expenses to children of Pennsylvania police and fire personnel killed in the line of duty.[36]

2005: Three of Barnes' original paintings were exhibited at London's Whitechapel Gallery in the 2005 Back to Black: Art, Cinema & Racial Imaginary art exhibition.[37]

2005: Kanye West commissioned Barnes to create a painting to depict his life-changing experience following his near-fatal car crash. A Life Restored measures 9 ft. x 10 ft. In the center of the painting is a large angel reaching out to a much smaller figure of West.[38]

October 2007: Barnes' final public exhibition. The National Football League and Time Warner sponsored A Tribute to Artist and NFL Alumni Ernie Barnes in New York City.

At the time of his passing, Barnes had been working on an exhibition Liberating Humanity From Within which featured a majority of paintings he created in the last few years of his life. Plans are under way for the exhibition to travel throughout the country and abroad.[39]

Television and movies

Barnes appeared on a 1967 episode of the game show To Tell the Truth. The panelists correctly guessed Barnes was the professional football player-turned-artist.

Barnes played Deke Coleman in the 1969 motion picture Number One, which stars Charlton Heston and Jessica Walter. Barnes played Dr. Penfield in the 1971 movie Doctors' Wives, which starred Dyan Cannon, Richard Crenna, Gene Hackman and Carroll O'Connor.

In 1971 Barnes, along with Mike Henry, created the Super Comedy Bowl, a variety show CBS television special which showcased pro athletes with celebrities such as John Wayne, Frank Gifford, Alex Karras, Joe Namath, Jack Lemmon, Lucille Ball, Carol Burnett and Tony Curtis. A second special aired in 1972.[40][41][42]

Throughout the Good Times television series (1974–79) most of the paintings by the character J.J. are works by Ernie Barnes. However a few images, including "Black Jesus" in the first season (1974), were not painted by Barnes. The Sugar Shack made its debut on the show's fourth season (1976–77) during the opening and closing credits. In the fifth season (1977–78) The Sugar Shack was only used in the closing credits for five early episodes during that season. In the sixth season (1978–79), The Sugar Shack was only used in opening credits for the first eight episodes and in the closing credits for five early episodes during that season. In the fifth and sixth seasons (1977–79), The Sugar Shack appears in the background of the Evans family apartment. Barnes had a bit part on two episodes of Good Times: The Houseguest (February 18, 1975) and Sweet Daddy Williams (January 20, 1976).

Barnes' artwork was also used on many television series, including Columbo, The White Shadow, Dream On, The Hughleys, The Wayans Bros., Wife Swap, and Soul Food, and in the movies Drumline and Boyz n the Hood.

In 1981 Barnes played baseball catcher Josh Gibson of the Negro League in the television movie Don't Look Back: The Story of Leroy ‘Satchel' Paige with Lou Gossett Jr. playing Paige.

The 2016 film Southside with You (about Barack and Michelle Obama's first date) prominently features Barnes' work in an early scene where the two characters visit an art exhibition.[43][44]

Death

Barnes passed away on Monday evening, April 27, 2009 at Cedars Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles, California from myeloid leukemia.[45] He was cremated and his ashes were scattered in two places: at his hometown Durham, North Carolina, near the site of where his family home once stood, and at the beach in Carmel, California, one of his favorite cities.

Notes

- Barnes, Ernie (1995). From Pads to Palette. Waco, Texas: WRS Publishing. ISBN 1-56796-064-2.

- Maher, Charles (May 7, 1968). "Artist's Portrait". Los Angeles Times.

- "The Beauty of the Ghetto" catalogue, Grand Central Art Galleries, New York, 1990 "Artist Statement"

- "Ernie Barnes Bio". artnet.com. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- "Ernie Barnes: An Athletic Artist". New York Times. May 7, 1984.

- Clark, N.P. (July 20, 1960). "Little Bunch of Colt Rookies Turn Up Big". The Baltimore News-Post.

- The Voice Newspapers. 1962–1963. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Ridgely, Roberta (February 1962). "The Times are Out of Joints". San Diego Magazine.

- Keen, Harold (July 1963). "San Diego's Racial Powder Keg". San Diego Magazine.

- "Two 'Gold Medalists' in Art, Barnes, Parmenter, Coming Here". Mobile Register. March 13, 1985.

- The National Sports Daily. December 14, 1990. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Rembrandt of the Broncos". Empire Magazine. December 6, 1964.

- Resonance, The Company of Art (newsletter), 1996.

- "People". Sports Illustrated. November 21, 1966. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- Merchant, Larry (November 19, 1966). "The Painter". The New York Post.

- Barnes, Ernie; Amdur, Neil (1971). "I Hate the Game I Love". Gridiron.

- Jr, Robert Mcg Thomas (January 27, 1997). "Ed Wilson, 71, a Sculptor and Art Teacher". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 4, 2019.

- Durham Morning Herald. November 1, 1973. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Interview, "Our World with Black Enterprise"

- Barnes, Ernie. Interview, "Personal Diaries" with Ed Gordon, BET, 1990

- The Atlanta Journal and Constitution. September 16, 1973. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "An Olympic Artist With A Message". Los Angeles Times. May 24, 1984.

- Long Beach Press Telegram. March 15, 1984. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "1984 & 2004 Sports Artist of the Year, Ernie Barnes, America's El Greco". ASAMA.org. The American Sport Art Museum & Archives. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- "Biography". ErnieBarnes.com. Archived from the original on December 16, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- "Top Black Painter Exhibits in Oakland". Oakland Tribune. August 14, 2002. Archived from the original on July 10, 2011. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- Barnes, Ernie. "Ernie Barnes Interview". SoulMuseum.net. Archived from the original on November 9, 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- Neal, Mark Anthony. Review: I Want You. PopMatters. Retrieved on October 26, 2010.

- Ritz (2003), pp. 2–3.

- Easter, Makeda (August 28, 2019). "Ernie Barnes' 'Sugar Shack': Why museum-goers line up to see ex-NFL player's painting". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- "Billboard Art". Los Angeles Times. May 29, 1992.

- Wharton, David (July 10, 1992). "Street Art". Los Angeles Times.

- "African-American Art: 20th Century Masterworks, II". Archived from the original on November 26, 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- Wellington, Elizabeth (May 8, 1998). "'The Advocate' will plead a special case". The News & Observer.

- Artist Statement in Commemorative catalogue for "The Advocate," May 7, 1998. Retrieved October 2010

- "Honorary Artwork". The Philadelphia Tribune. July 12, 2002.

- "Back to Black – Art, Cinema and the Racial Imaginary". Whitechapel Gallery. 2005. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved October 28, 2010.

- "Kanye West denies angel likeness in painting". NME. July 7, 2008. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- "Remembering Ernie Barnes". CNN. November 27, 2009. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- "'Super Comedy Bowl' Features Stars, Players". Los Angeles Times. January 9, 1971.

- Los Angeles Times. November 23, 1971. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Los Angeles Times. January 9, 1972. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - McCarthy, Todd (January 24, 2016). "'Southside With You': Sundance Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- Valentine, Victoria L. (September 5, 2016). "In First Date Movie 'Southside With You,' Paintings by Ernie Barnes Fuel Connection Between Barack and Michelle Obama". Culture Type. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

The Obamas have said they went to the Art Institute of Chicago, but Tanne didn’t know what they saw when they got there. The museum’s summer 1989 schedule included an Andy Warhol retrospective, but there is no mention of an African American art exhibition. Tanne improvised, introducing the work of Los Angeles-based Barnes, a former professional football player. “I just became so enamored again with Ernie Barnes’s art because he covered such a broad spectrum of life in America, and of black life in America,” Tanne told vanityfair.com. “It just seemed like there could really be a lot of artwork to get them talking to each other.”

- Weber, Bruce (April 30, 2009). "Ernie Barnes, Artist and Athlete, Dies at 70". The New York Times. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

References

- Historic Preservation Society of Durham (2008). Brighter Leaves. BPR Publishers.

- Hills, Patricia; Renn, Melissa (2005). Syncopated Rhythms. Boston University Art Gallery.

- Von Blum, Paul (2004). Resistance, Dignity and Pride. University of California; Los Angeles. Center for African American Studies. CAAS Publications.

- Tobias, Todd (2004). Charging Through The AFL: Los Angeles And Sand Diego Chargers' Football In The 1960s. Turner Publishing Company (KY).

- Hurd, Michael (2000). Black College Football, 1892–1992: One Hundred Years Of History, Education & Pride. Donning Company Publishers.

- Carroll, Bob (1999). Total Football. HarperCollins.

- Trocki, Philip K. (1998). Spell It Out. Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Powell, Richard J. (1997). Black Art And Culture In The 20th Century (World Of Art). Thames & Hudson.

- Riggs, Thomas (1997). St. James Guide To Black Artists Edition 1 (St. James Guide To Black Artists). Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. St. James Press.

- Barnes, Ernie (1994). From Pads To Palette. WRS Publishing.

- Anderson, Jean Bradley (1990). Durham County. Duke University Press.

- Bradbury, Ray. Missing or empty

|title=(help)