Elizabethan architecture

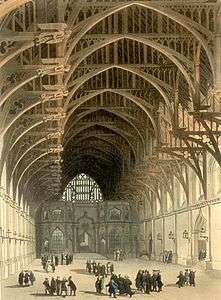

Elizabethan architecture refers to buildings of a certain style constructed during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I of England and Ireland from 1558–1603.[1] Historically, the era sits between the long era of dominant architectural style of religious buildings by the Catholic Church, which ended abruptly at the Dissolution of the Monasteries from c.1536, and the advent of a court culture of pan-European artistic ambition under James I (1603–25). Stylistically, Elizabethan architecture is notably pluralistic. It came at the end of insular traditions in design and construction called the Perpendicular style in church building, the fenestration, vaulting techniques and open truss designs of which often affected the detail of larger domestic buildings. However, English design had become open to the influence of early printed architectural texts (namely Vitruvius and Alberti) imported to England by members of the church as early as the 1480s. Into the 16th century, illustrated continental pattern-books introduced a wide range of architectural exemplars, fueled by the archaeology of classical Rome which inspired myriad printed designs of increasing elaboration and abstraction.

_cropped_2.jpg)

As church building turned to the construction of great houses for courtiers and merchants, these novelties accompanied a nostalgia for native history as well as huge divisions in religious identity, plus the influence of continental mercantile and civic buildings. Insular traditions of construction, detail and materials never entirely disappeared. These varied influences on patrons who could favour conservatism or great originality confound attempts to neatly classify Elizabethan architecture. This era of cultural upheaval and fusions corresponds to what is often termed Mannerism and Late Cinquecento in Italy, French Renaissance architecture in France, and the Plateresque style in Spain.[1]

In contrast to her father Henry VIII, Elizabeth commissioned no new royal palaces, and very few new churches were built, but there was a great boom in building domestic houses for the well-off, largely due to the redistribution of ecclesiastical lands after the Dissolution. The most characteristic type, for the very well-off, is the showy prodigy house, using styles and decoration derived from Northern Mannerism, but with elements retaining signifies of medieval castles, such as the normally busy roof-line.

History

The Elizabethan era saw growing prosperity, and contemporaries remarked on the pace of secular building among the well-off. The somewhat tentative influence of Renaissance architecture is mainly seen in the great houses of courtiers, but lower down the social scale large numbers of sizeable and increasingly comfortable houses were built in developing vernacular styles by farmers and townspeople. Civic and institutional buildings were also becoming increasingly common.

Renaissance architecture had achieved some influence in England during the reign of, and mainly in the palaces of, Henry VIII, who imported a number of Italian artists. Unlike Henry, Elizabeth built no new palaces, instead encouraging her courtiers to build extravagantly and house her on her summer progresses. The style they adopted was more influenced by the Northern Mannerism of the Low countries than Italy, among other features it used versions of the Dutch gable, and Flemish strapwork in geometric designs. Both of these features can be seen on the towers of Wollaton Hall and again at Montacute House. Flemish craftsmen succeeded the Italians that had influenced Tudor architecture; the original Royal Exchange in London (1566–1570) is one of the first important buildings designed by Henri de Paschen, an architect from Antwerp.[1] However, most continental influence came from books, and there were a number of English "master masons" who were in effect architects and in great demand, so that their work is often widely spread around the country.

Important examples of Elizabethan architecture include:

- Audley End

- Blickling Hall

- Charterhouse (London)

- Condover Hall (Shropshire)

- Danny House

- Hatfield House

- Longleat House

- Wollaton Hall

- Rainthorpe Hall

In England, the Renaissance first manifested itself mainly in the distinct form of the prodigy house, large, square, and tall houses such as Longleat House, built by courtiers who hoped to attract the queen for a ruinously expensive stay, and so advance their careers. Often these buildings have an elaborate and fanciful roofline, hinting at the evolution from medieval fortified architecture.

It was also at this time that the long gallery became popular (for the Aristocracy) in English houses. This was apparently mainly used for walking in, and a growing range of parlours and withdrawing rooms supplemented the main living room for the family, the great chamber. The great hall was now mostly used by the servants, and as an impressive point of entry to the house.

Surveyors (architects) active in this period

- Robert Adams (1540–1595)

- William Arnold (fl. 1595–1637)

- Simon Basil (fl. 1590–1615)

- Robert Lyminge (fl. 1607–1628)

- Robert Smythson (1535–1614)

- John Thorpe or Thorp (c.1565–1655?; fl.1570–1618)

See also

- Tudorbethan and Jacobethan, revivals derived (in part) from Elizabethan architecture

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 288.

Sources

- Airs, Malcolm, The Buildings of Britain, A Guide and Gazetteer, Tudor and Jacobean, 1982, Barrie & Jenkins (London), ISBN 0091478316

- Girouard, Mark, Life in the English Country House: A Social and Architectural History 1978, Yale, Penguin etc.

- Jenkins, Simon, England's Thousand Best Houses, 2003, Allen Lane, ISBN 0713995963

- Summerson, John, Architecture in Britain, 1530 to 1830, 1993 edition, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, Yale University Press, ISBN 0300058861, ISBN 9780300058864

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Elizabethan architecture. |

- Shaw, Henry (1839). Details of Elizabethan architecture. London: William Pickering – plates of architectural details