Eleftherios Handrinos

Eleftherios Handrinos (also spelled Chandrinos, Greek: Ελευθέριος Χανδρινός; 18 September 1937 – 27 July 1994) was a Hellenic Navy officer who retired with the rank of vice admiral. He is notable for his involvement in the first Turkish invasion of Cyprus, during which he commanded an LST vessel that caused confusion among Turkish commanders, leading to the loss of a Turkish destroyer due to friendly fire.[1] He also served as a naval attaché in Ankara.[3]

Eleftherios Handrinos | |

|---|---|

| Born | 18 September 1937 Komotini |

| Died | 27 July 1994 Athens |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Hellenic Navy |

| Years of service | 1954–1992 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | Turkish invasion of Cyprus |

Early life and career

Handrinos was born in Komotini to parents who came from the island of Corfu. His parents were Konstantinos, a major general in the Greek Army who was serving in Thrace at the time, and Maria Handrinos (née Drazinou). At the age of fourteen, his family moved to Athens and in 1954 he entered the Hellenic Naval Academy, graduating as an ensign in June 1958. Following his graduation, he served on several navy ships and was trained on anti-submarine warfare in the United States. For a period of four years, he also served with the 353 Naval Collaboration Squadron (353 MNAS) flying with SHU-16B aircraft.

Cyprus 1974

Background

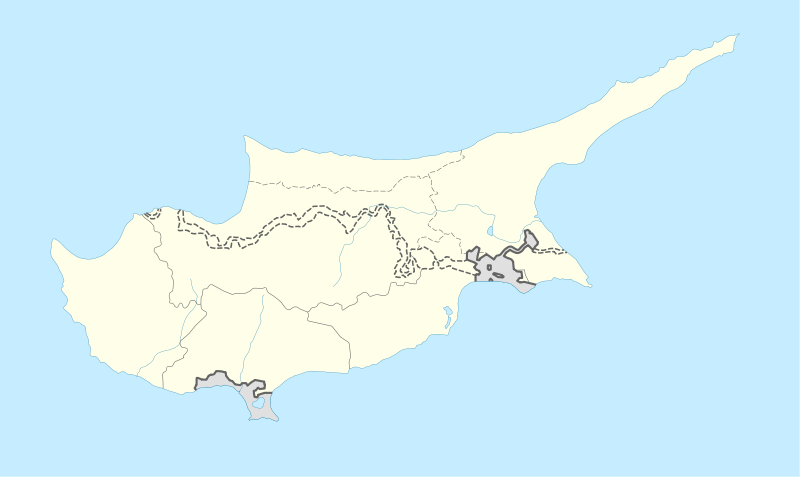

On 15 July 1974, a military coup d'état orchestrated by the right-wing military junta of Athens and the Cypriot National Guard deposed the Cypriot President Makarios. With the pretext of a peacekeeping operation, Turkey took military action and invaded Cyprus west of Kyrenia in the dawn of 20 July 1974.[4]

Famagusta mission

In the summer of 1974, Handrinos had risen to the rank of Lieutenant commander. Since 1 August 1973, he had been commanding landing ship Lesvos (L-172, ex USS Boone County). On 12 July 1974, Lesvos was scheduled to depart from the small harbour of Kechries in Corinthia bound for Famagusta, carrying 450 replacement personnel and provisions for the permanent Hellenic Force in Cyprus (ELDYK). The estimated time for arrival in Famagusta was the early morning of July 17. The departure was delayed for 24 hours and the ship sailed on the late evening of July 13. En route to Cyprus, the ship picked up broadcasts by the radio station of Nicosia, from which Handrinos was informed about the coup that had been launched against President Makarios. On July 16, while the ship was off the coast of Limassol, the Hellenic Navy HQ ordered Handrinos to return to Greek waters by changing course towards Lindos in Rhodes.[3] This was probably due to the Greek junta being unwilling to give the impression of reinforcing the Greek forces on Cyprus. As the situation in Cyprus became more stable and the coup seemed successful, Handrinos was ordered to sail again towards Cyprus. In the afternoon of July 19, only a few hours before the Turkish invasion, Lesvos dropped anchor in the port of Famagusta. After the disembarkation of the replacement troops, another 450 soldiers who were being discharged or relocated from ELDYK to Greece came aboard. The ship then departed at around 18:00 heading for Greece.[5]

Shelling at Paphos

In the morning of July 20, Handrinos was informed by a radio broadcast about the ongoing Turkish invasion. Soon after, when Lesvos was approximately 40 nm from Paphos, Handrinos received an order to sail east and disembark in Limassol the troops he had picked up the day before. This order was later canceled, and the ship was ordered to sail to Paphos. In his official report, Handrinos notes that the return to Cyprus and the prospect of fighting against the invading Turkish forces was welcomed with enthusiasm by the troops onboard Lesvos.[3][5]

At around 14:00, Lesvos anchored off the port of Paphos and the troops begun to be offloaded with small landing crafts. While the disembarkation was still in progress, Handrinos was asked by the local commander of the Cypriot National Guard to attack the fortified positions of Turkish and Turkish Cypriot forces in the nearby enclave of Mouttalos (Greek: Μούτταλος). Without clear rules of engagement from Athens, Handrinos decided to bombard the enclave with the ship's twin 40 mm Bofors guns.[3][5] Due to the lack of sufficient naval personnel onboard Lesvos, its guns were manned by ELDYK men who had received brief, on the spot training while at sea earlier that day. Over 900 shells were fired in a period of two hours, which exceeded the time required for disembarkation and resulted in the surrender of two heavily armed Turkish companies.[5]

Handrinos was aware that his slow and lightly armed ship was an easy target for patrolling Turkish warships and jet fighters. Therefore, in the late afternoon of July 20 and immediately after the shelling, he departed Paphos to seek cover in the coming darkness. Knowing that the Turkish air force would search for his ship in the sea region between Cyprus and Rhodes, Handrinos executed an evasive maneuver by first steering his ship south towards Egypt, later heading west and turning north towards Crete only when he was more than 60 nm away from Cyprus.[5] In this manner, Lesvos managed to remain undetected and safely reached Salamis naval base on July 23, after an intermediate stop at Sitia.[5]

Aftermath

_underway%2C_between_1962_and_1972_(NH_82585).jpg)

Despite not being a front line ship, Lesvos was the only vessel of the Hellenic Navy that fought during the Turkish invasion in Cyprus. A direct consequence of the Paphos bombardment was that it neutralized the Turkish stronghold and helped decisively to maintain the city in Greek hands. The troops which were disembarked at Paphos were transported by buses to the ELDYK barracks in Nicosia. They assumed active combat duties and fought gallantly during the second phase of the Turkish invasion in mid August 1974.

As a result of the shelling at Paphos, Turkish reports about an escorted Greek ship convoy carrying reinforcements started to float around. The confusion was further aggravated by radio conversations among National Guard units, who knowing that their communications were being monitored, intentionally mentioned that Greek Navy vessels were off Paphos. Based on these reports, in the morning of 21 July the Turkish naval command ordered three destroyers accompanying the landing force at Kyrenia to sail west and intercept the supposed Greek convoy. These were TCG Kocatepe (D354), TCG Adatepe (D353) and TCG Mareşal Fevzi Çakmak (D351).[6] Around noon, the destroyers were heading south towards Paphos but were unable to spot any ships. In the meantime, the Turkish air force had received reports who mistook the three Turkish destroyers as being Greek and had ordered their sinking. Thus, around 14:00, three Turkish air force squadrons (namely 181, 141 and 111 Filo) totaling 48 F-100D and F-104G aircraft armed with bombs and rockets, took off from three different airports in southern Turkey. The Turkish destroyers were spotted by the aircraft pilots at 15:00, who noticed that they were flying Turkish flags. Considering this to be a Greek deception, they started to fire their rockets and drop their bombs at the destroyers, which responded with anti-aircraft guns. Eventually, the ships managed to identify the attacking aircraft. Despite repeated attempts by the Turkish ships to convince the pilots about their nationality, the air attacks continued.[note 1] The strikes resulted in Kocatepe being sunk and taking with her several dozens of sailors, Adatepe being extensively damaged and Çakmak suffering minor damage. At least one aircraft was also shot down by anti-aircraft fire.[5]

Later life

As was the case with other Greek soldiers who saw military action in Cyprus, Handrinos received no honors or public recognition while he was alive. He was honored posthumously only in 2015.[7] For several decades after the restoration of democracy, the rationale of the Greek state was that since Greece was not officially at war with Turkey in 1974, no combat operations involving Greeks could have taken place. In 1982, Handrinos was promoted to captain and in 1984 he was appointed as a military attaché in Ankara. In May 1986, while driving near Komotini en route from Athens to Ankara, Handrinos was seriously injured in a car accident. The cause of that accident was not determined, and Handrinos never fully recovered from it. He retired on 26 March 1992 and died on 27 July 1994.

See also

Notes

- Birand reports that Çakmak was carrying a downed Turkish pilot who had been rescued from the sea on the previous day (20 July). This pilot came to the radio and asked his colleagues to abort the attacks. When they asked for the current password, he was unaware of it, hence his pleas were ignored.[6]

References

- Ι. Γ. Μπήτος. Από την Πράσινη Γραμμή στους δύο Αττίλες, β' έκδοση, Εταιρεία Μελέτης Ελληνικής Ιστορίας, Αθήνα 1998, σελ. 237-241

- Αρματαγωγό «Λέσβος»: Μια ιστορία ηρώων που χάθηκε στην ντροπή της προδοσίας, Proto Thema online, 15/078/2013, archived here

- Andreas Constandinos. America, Britain and the Cyprus Crisis of 1974: Calculated Conspiracy or Foreign Policy Failure?, AuthorHouse, 2009. ISBN 1438989067

- Το «Λέσβος» και η αεροναυμαχία της Πάφου, I. Paloumpis, archived here

- Mehmet Ali Birand, 30 Sicak Gün [Thirty Hot Days], Milliyet, Istanbul, 1976

- "Απονομή Διαμνημόνευσης Αστέρα Αξίας και Τιμής από τον ΥΕΘΑ Πάνο Καμμένο στον αποβιώσαντα Αντιναύαρχο ε.α. Ελευθέριο Χανδρινό" (in Greek). Hellenic Ministry of Defence. 19 November 2015. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

External links

- Λέσβος L-172 (1960-1990), from Hellenic Navy

- Λέσβος (L 172) from hellasarmy.gr

- Kocatepe wreck