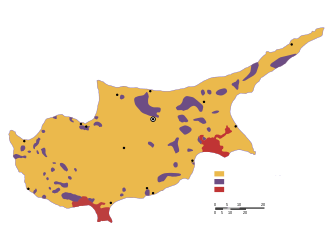

Turkish Cypriot enclaves

The Turkish Cypriot enclaves were inhabited by Turkish Cypriots between the intercommunal violence of 1963–64 and the 1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus.

Events leading to the creation of the enclaves

In December 1963 the President of the Republic of Cyprus, Archbishop Makarios, citing Turkish Cypriot tactics aimed at obstructing the normal functioning of government, proposed several amendments to the post-colonial constitution of 1960. This precipitated a crisis between the Greek Cypriot majority and the Turkish Cypriot minority, and Turkish Cypriot representation in the government ended. The nature of this event is controversial. Greek Cypriots claim that Turkish Cypriots voluntarily withdrew from the institutions of the Republic of Cyprus, while the Turkish Cypriot narrative has it that the Turkish Cypriots were forcibly excluded.[2]

After the rejection of the constitutional amendments by Turkey on 16 December 1963 island-wide intercommunal violence broke out. The Turkish Cypriot narrative claims that 103 to 109 Turkish Cypriot or mixed villages were attacked and 25,000–30,000 Turkish Cypriots became refugees.[3][4] Greek Cypriots claim that many Turkish Cypriots were encouraged or coerced into leaving their villages by the Turkish Cypriot paramilitary organisation TMT, which wished to corral the Turkish minority into larger villages to create partition on the ground and in preparation for an anticipated military intervention from Turkey, which would seal taksim or partition. Official figures show that during fighting between 21 December 1963 to 10 August 1964, 364 Turkish Cypriots and 174 Greek Cypriots were killed.[5]

Situation in the enclaves

Since the enclaves, scattered all over the island, were regarded by the Greek Cypriots as armed camps that aimed to undermine the state and prepare the way for a Turkish invasion, restrictions were imposed on who and what could go in and out of them. However, the Cyprus government soon came to realise that these restrictions were, in fact, counterproductive and served the Turkish goal of increasing animosity between Greek and Turkish Cypriots, creating de facto partition and alienating Turkish Cypriots from the Republic of Cyprus. Thus, after 1967, restrictions on the enclaves were eased and many Turkish Cypriots, despite opposition from the TMT, began to return to the villages they had left in 1963.

Ban on goods

The Republic of Cyprus banned the possession of certain items by Turkish Cypriots and the entrance of these items to the enclaves. For the island's government these restrictions were aimed at curtailing the military activities of Turkish Cypriots, but Turkish Cypriots claim they were also meant to stifle economic activity and force the Turkish Cypriots to accept Greek Cypriot political dominance. Below is a list of banned items as of 7 October 1964, according to a report by the United Nations Secretary-General:[6]

|

|

|

Travel restrictions

The fear that Turkish Cypriots were engaged in a military build up with weapons and men smuggled in from Turkey was behind restrictions that the Cyprus government imposed on freedom of movement of Turkish Cypriots in the period 1963–67. Greek Cypriot police committed what was called by the UN Secretary-General "excessive checks and searches", [6] while Turkish Cypriots claimed they suffered harassment by Greek Cypriot officers at control points, airports and government offices.[7] The Secretary-General also noted his concerns about arbitrary arrest and detention. However, in his report to the UN Security Council on 6 March 1964, Secretary General U Thant also made clear that:

The Turkish Cypriot leaders have adhered to a rigid stand against any measures which might involve having members of the two communities live and work together, or which might place Turkish Cypriots in situations where they would have to acknowledge the authority of Government agents. Indeed, since the Turkish Cypriot leadership is committed to physical and geographical separation of the communities as a political goal, it is not likely to encourage activities by Turkish Cypriots which may be interpreted as demonstrating the merits of an alternative policy. The result has been a seemingly deliberate policy of self-segregation by the Turkish Cypriots. [8]

Economic situation

This policy of self-segregation saw widening economic disparities between the two communities. While the Greek Cypriot economy benefited from flourishing tourism and finance sectors, Turkish Cypriots grew increasingly poor and unemployment increased.[9]

List of Turkish Cypriot enclaves

- Kokkina (Erenköy)

- Limnitis (Yeşilırmak)

- Lefka (Lefke)

- Lefkosia-Agyrta (Lefkoşa-Ağırdağ)

- Tsatos (Tziaos/Serdarlı)

- Galinoporni (Kuruova)

- Kophinou (Geçitkale)

- Lourojina (Akincilar)

- Angolemi (Gaziveren)

- Pergamos (Beyarmudu)

Smaller enclaves within the main cities:

- Pafos (Mouttalos/Kasaba)

- Larnaka (İskele)

- Famagusta (Mağusa/Suriçi)

References

- "Cyprus Ethnic 1973".

- Ker-Lindsay, James (2011). The Cyprus Problem: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford University Press. pp. 35–6. ISBN 9780199757169.

- John Terence O'Neill, Nicholas Rees. United Nations peacekeeping in the post-Cold War era, p.81

- Hoffmeister, Frank (2006). Legal aspects of the Cyprus problem: Annan Plan and EU accession. EMartinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 17–20. ISBN 978-90-04-15223-6.

- Oberling, Pierre. The road to Bellapais (1982), Social Science Monographs, p.120: "According to official records, 364 Turkish Cypriots and 174 Greek Cypriots were killed during the 1963–1964 crisis."

- "REPORT BY THE SECRETARY-GENERAL ON THE UNITED NATIONS OPERATION IN CYPRUS (For the period 10 September to 12 December 1964) – Annex II. Doc S/6103" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- Asmussen, Jan (2014). "Escaping the Tyranny of History". In Ker-Lindsay, James (ed.). Resolving Cyprus: New Approaches to Conflict Resolution. I.B.Tauris. p. 35. ISBN 9781784530006.

- "S/5950 UN Documents".

- Ker-Lindsay, James, ed. (2014). Resolving Cyprus: New Approaches to Conflict Resolution. I.B.Tauris. p. 35. ISBN 0857736019.

See also

- History of Cyprus

- Cyprus dispute

- Modern history of Cyprus

- Enclave